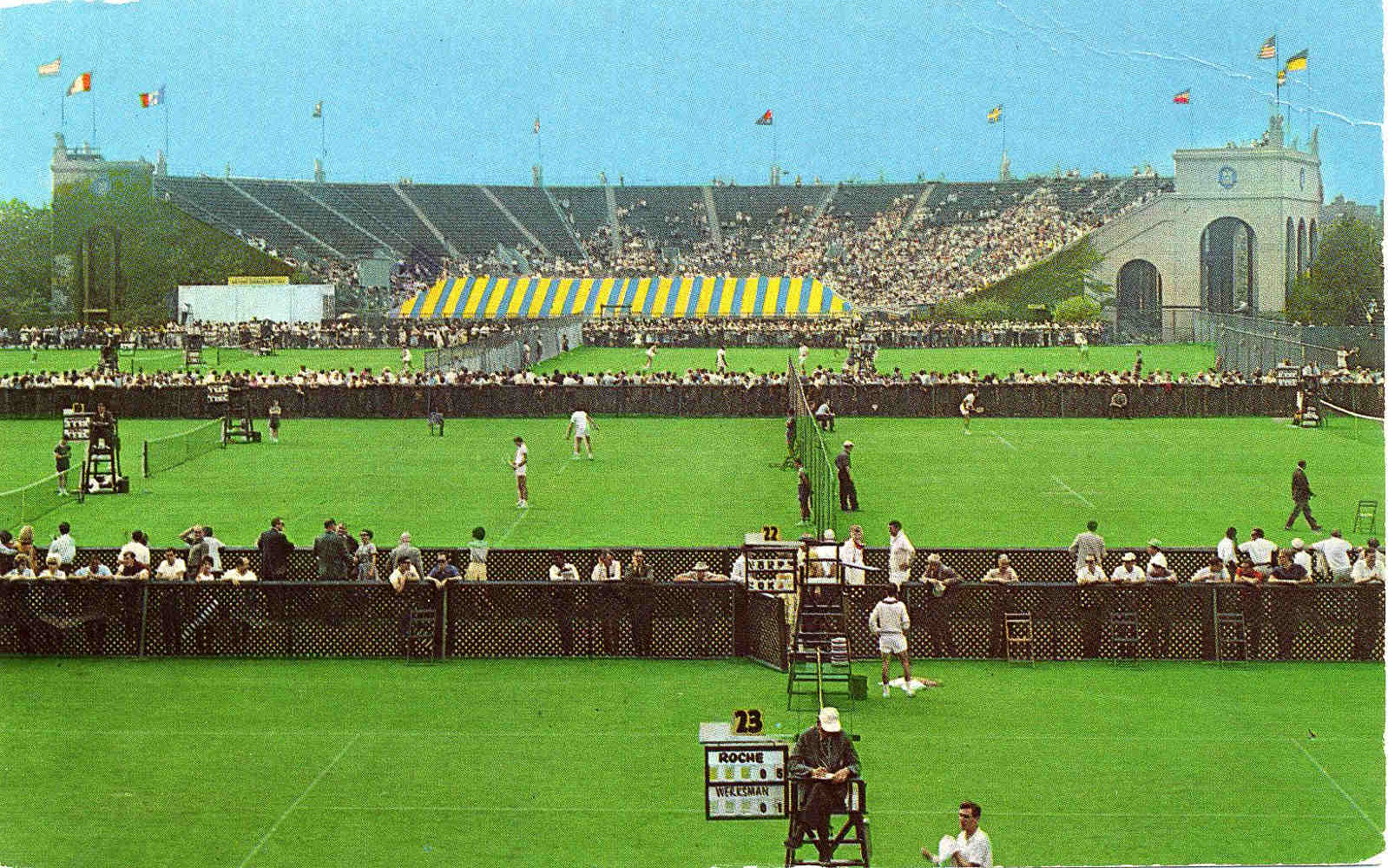

West Side Tennis Club

overview

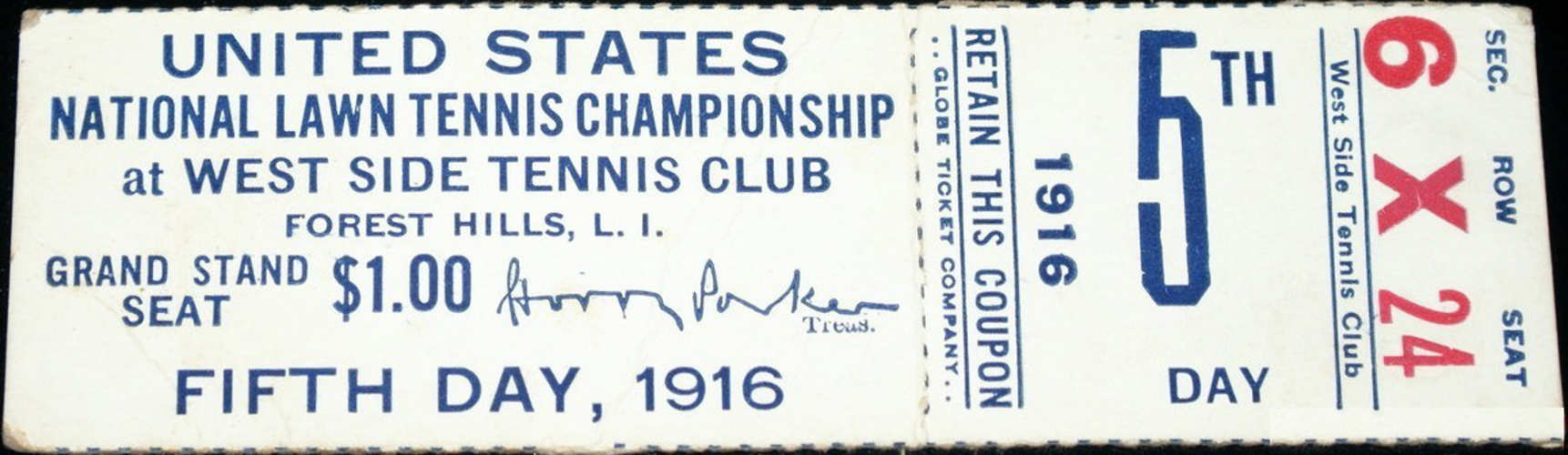

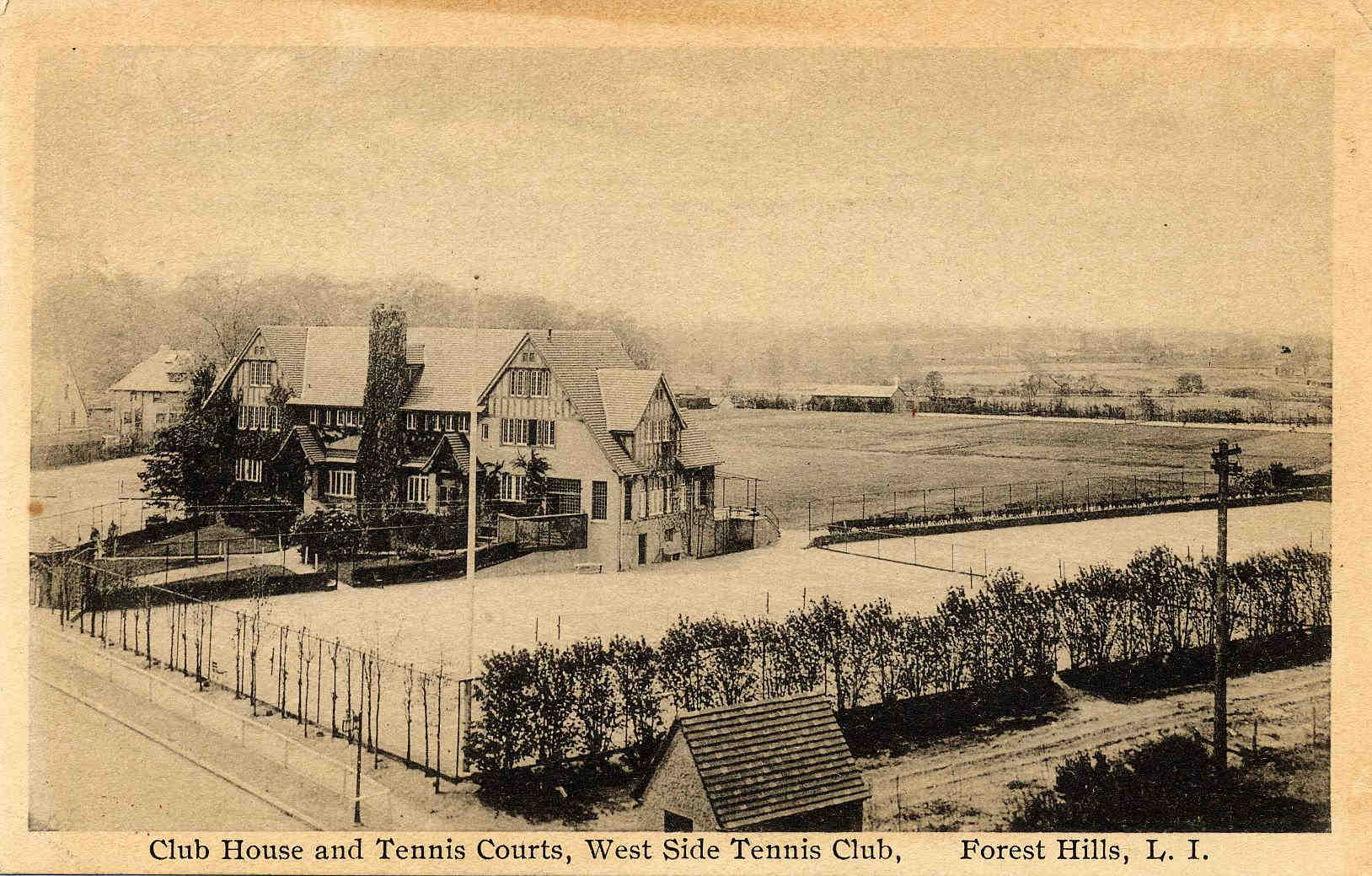

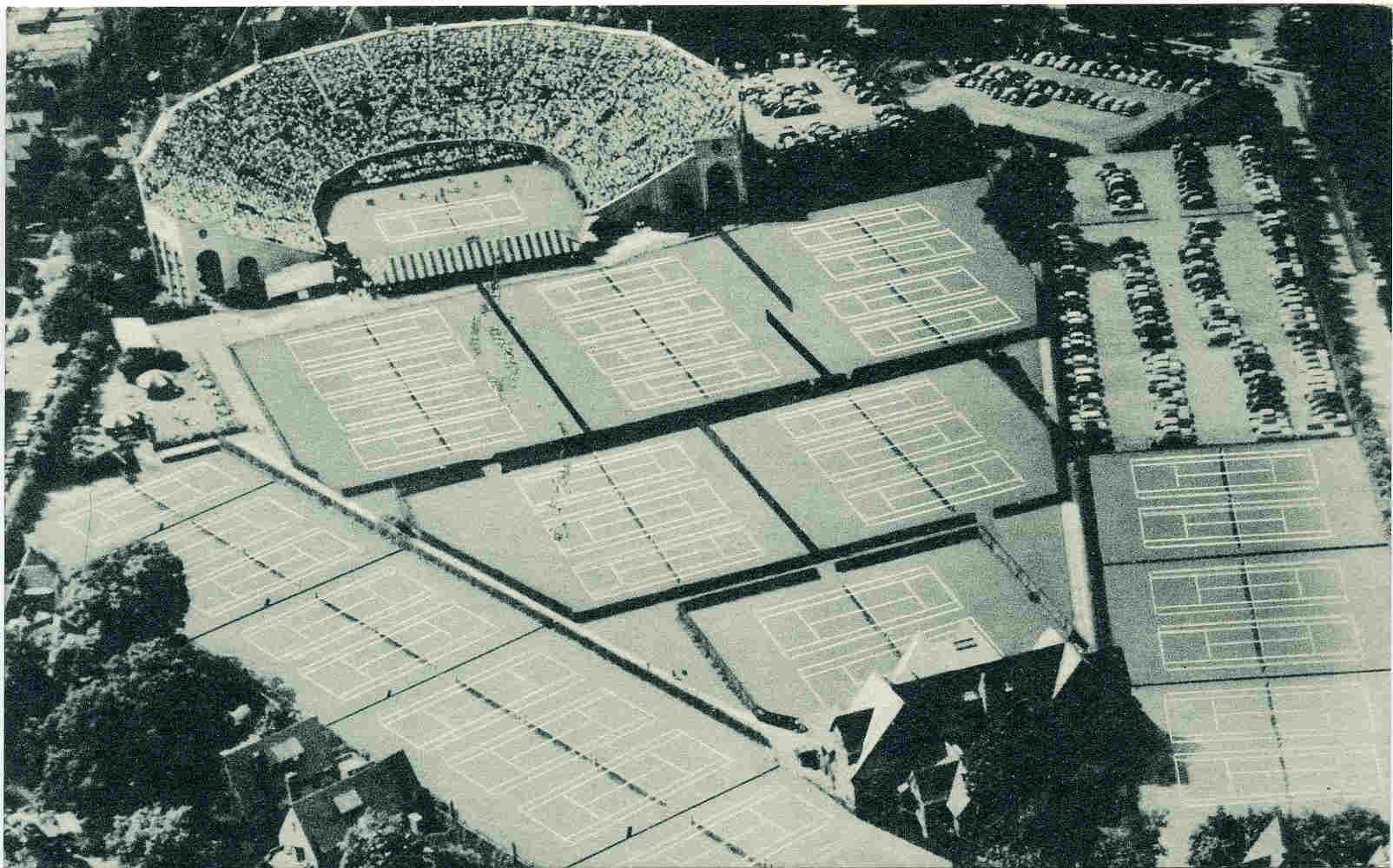

The West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills began hosting a portion of the U.S. Open (originally known as the U.S. National Championships) in 1915 and was the sole location for the entire tournament between 1942 and 1945 and 1968 to 1977.

Notable LGBT players Eleonora Sears, Bill Tilden, Gottfried von Cramm, Billie Jean King, Martina Navratilova, and Renée Richards competed here until the U.S. Open moved to its current location in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens, in 1978.

History

The U.S. Open (known formally as the U.S. Open Tennis Championships) originated in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1881 as the U.S. National Championships (changing to its current name in 1968). The tournament’s five events were held in different locations for decades. The West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, Queens, started hosting the men’s and women’s singles championships in 1915 and 1921, respectively, intermittently hosting men’s doubles, women’s doubles, and mixed doubles over the years. From 1942 to 1945 and from 1968 to 1977, it was the sole location for the tournament. In need of a larger facility as the popularity of professional tennis grew, the U.S. Open moved to the newly constructed USTA National Tennis Center (now the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center) in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens, in 1978.

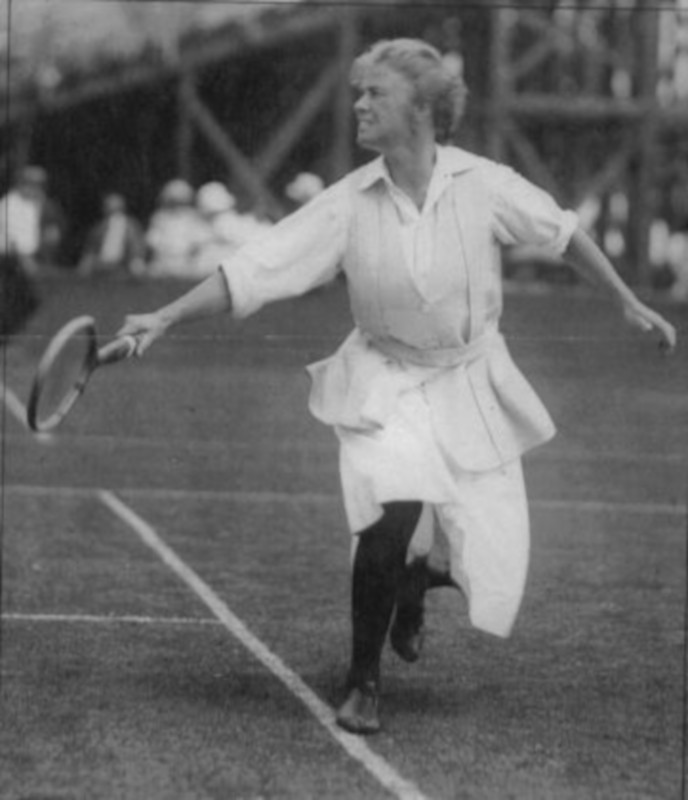

Eleonora Sears (1881-1968) was a pioneering female athlete in the first half of the 20th century. Born into wealth, she was introduced to tennis and other high society sports. She competed at the West Side Tennis Club in the 1920s, but won her earlier U.S. National Championships titles in women’s singles, women’s doubles, and mixed doubles at the Philadelphia Cricket Club in the 1910s (the location of these three events from 1892 to 1920). Author Peggy Miller Franck, whose father was Sears’ financial advisor and managed her racing stable, wrote Prides Crossing: The Unbridled Life and Impatient Times of Eleonora Sears (2012), in which she notes that Sears was openly lesbian (though did not use that label) and had several same-sex relationships that most people knew about. In the 1930s, she had a relationship with socialite Isabel Pell.

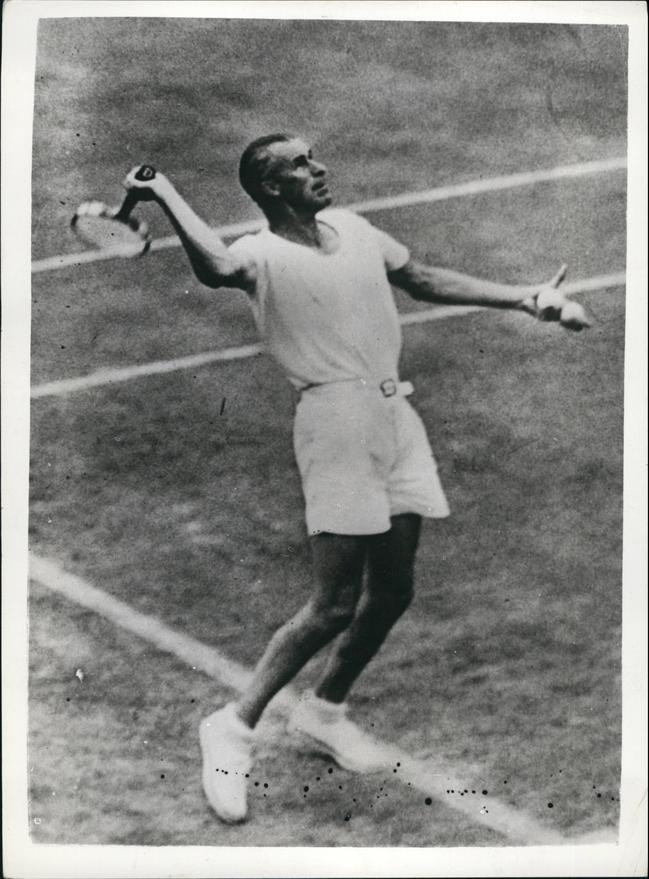

Bill Tilden (1893-1953), an openly gay athlete who went by “Big Bill,” is considered the first superstar in tennis. The sport’s mainstream popularity today is attributed to Tilden, who helped move tennis away from being an exclusively high society game. He first competed at the West Side Tennis Club in 1915 and won six titles in a row from 1920 to 1925 (three of which took place here), a record he still holds. He also won here in 1929 and 1931. However, Tilden’s influence on the sport is rarely discussed today because of charges he faced in the 1940s involving sexual encounters with teenage boys.

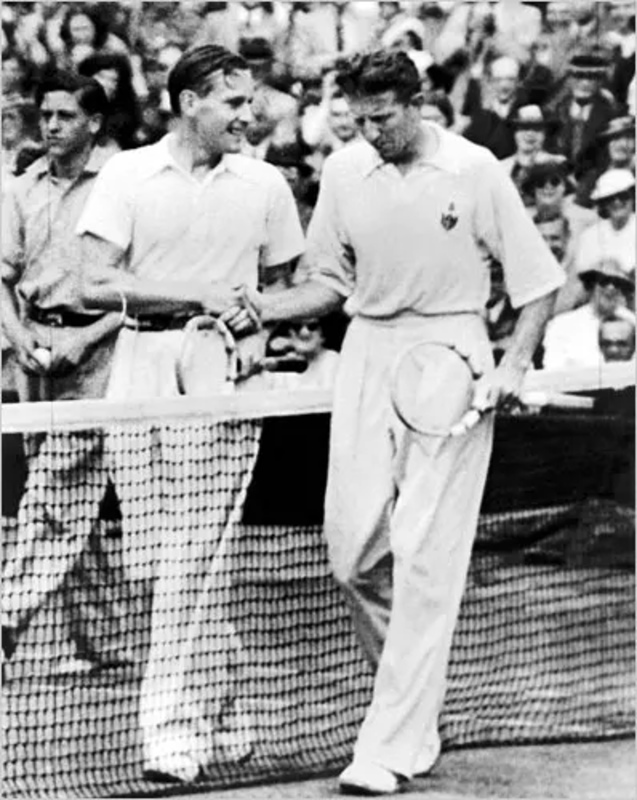

The German tennis player Gottfried von Cramm (1909-1976) was one of the best in the world in the 1930s, and the top seed in 1937. That year, he lost to American player Don Budge in the finals of the U.S. National Championship at the West Side Tennis Club as well as the Davis Cup and Wimbledon, both held at the All England Club. These widely watched losses, along with von Cramm’s refusal to join the Nazi party and his criticism of Hitler, ended his usefulness as the Aryan sports ideal in Nazi propaganda. Von Cramm was incarcerated under Paragraph 175 for homosexuality in 1938. Budge collected signatures from prominent athletes for a letter sent to Germany, in an attempt to get von Cramm released. After his stay in prison, von Cramm attempted to play at Forest Hills in 1939, but was denied a visa due to this arrest. After the war, many countries continued to deny him a visa to play in tournaments.

Women’s and LGBT rights spokesperson Billie Jean King (b. 1943) was the top-seeded women’s player in the world for several years in the 1960s and 1970s. At the West Side Tennis Club, she became the first player to win a Grand Slam event using a metal racket in 1967. She was also the U.S. Open champion here in 1971, 1972, and 1974. King’s pioneering efforts to achieve gender equality in the sport led to the current U.S. Open complex being rededicated the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in 2006.

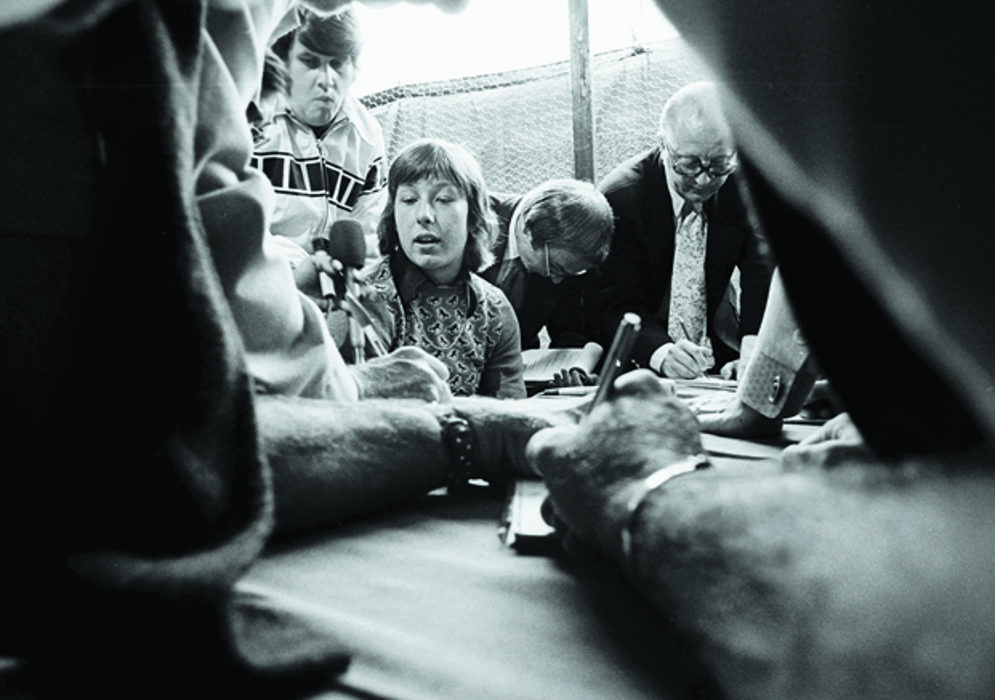

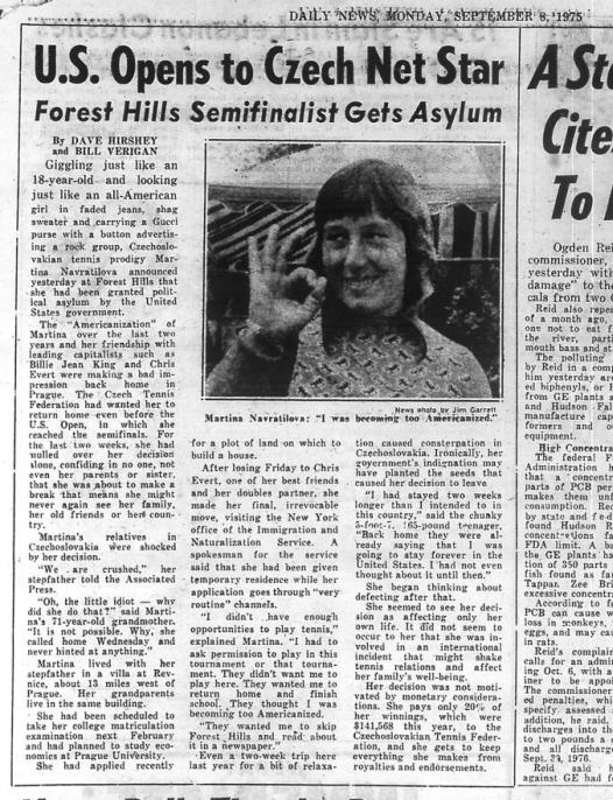

Future four-time U.S. Open singles champion Martina Navratilova (b. 1956) announced that she was defecting from Czechoslovakia to the United States at the end of the 1975 U.S. Open. The jam-packed press conference has since been considered the biggest tennis story of that year. Navratilova is one of the most decorated players in the history of tennis.

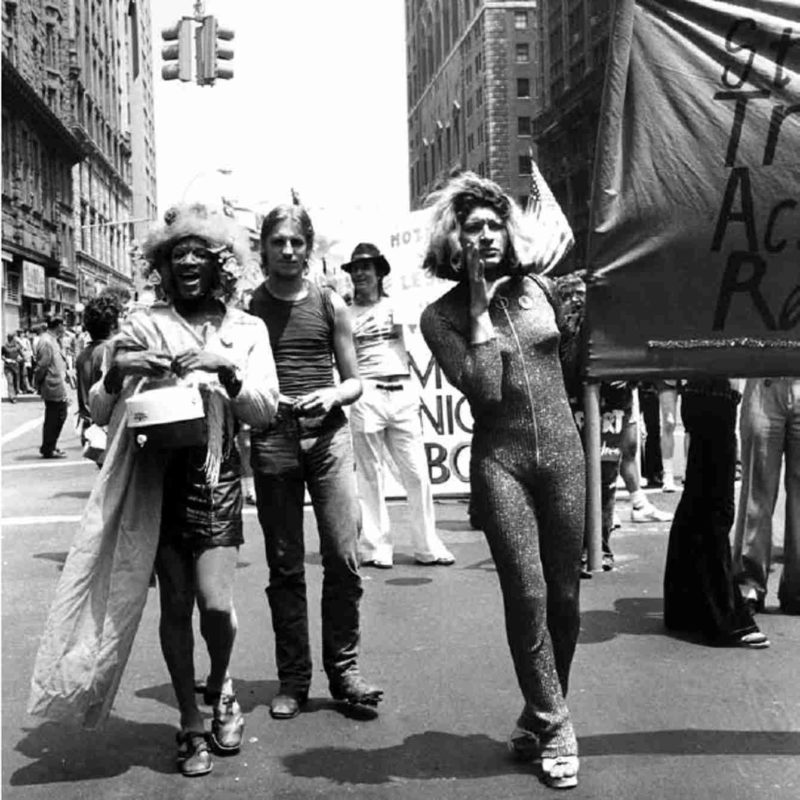

At the 1977 U.S. Open, its last year at this venue, Renée Richards (b. 1934) became the first trans woman to compete in a professional tennis tournament. The Sunnyside, Queens, native underwent gender reassignment surgery in 1975. As controversy grew over whether she should be allowed to compete in women’s tournaments a year later, the United States Tennis Association (USTA) made a chromosome test mandatory for female entrants for the first time in its history. Richards sued, and the New York Supreme Court ultimately ruled in her favor.

My lawyer handed over an affidavit from Billie Jean King that said she had met me, that I was a woman, that I was entitled to play, and that I couldn’t be denied. And that was it. We won.

The event is considered a huge victory for transgender rights. Richards, who would go on to coach Navratilova, eventually returned to the medical field. She would become the surgeon director of ophthalmology and head of the eye-muscle clinic at the Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital on the Upper East Side.

Of this list, the following players were inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island: Tilden (1959), Sears (1968), von Cramm (1977), King (1987), and Navratilova (2000). King, Navratilova, and Richards were in the first class of inductees to Chicago’s National Gay and Lesbian Sports Hall of Fame in 2013.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (March 2017; last revised January 2024).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Grosvenor Atterbury (clubhouse); Kenneth M. Murchison (stadium)

- Year Built: 1913-14 (clubhouse); 1923 (stadium)

Sources

Alessandra Stanley, “The Legacy of Billie Jean King, an Athlete Who Demanded Equal Pay,” The New York Times, April 26, 2006.

“Eleonora Sears,” International Tennis Hall of Fame, bit.ly/3z5PDks.

Frank Deford, Big Bill Tilden: The Triumphs and the Tragedy (New York: Sportsclassic Books, 2004).

“Gottfried von Cramm,” Spartacus Educational, bit.ly/4aImePK.

John Carvalho, “Bill Tilden: The Flawed Life of a Gay Tennis Icon,” Outsports, June 24, 2014, bit.ly/2fzyHOd.

Josh Hinkle, “The Woman Behind Title IX,” Advocate, May 17, 2012, bit.ly/32HQzzi.

Robin Herman, “‘No Exceptions,’ and No Renée Richards,” The New York Times, August 27, 1976.

Ross Forman, “Athlete Eleonora ‘Eleo’ Sears, a lesbian, profiled in new book,” Windy City Times, February 2, 2012, bit.ly/3sNHdND.

Sara Lentati, “Tennis’s Reluctant Transgender Pioneer,” BBC Magazine, June 26, 2015, bbc.in/2fICxni. [source of pull quote]

Steve Tignor, “1975: Martina Navratilova Defects to the U.S. While Playing the U.S. Open,” Tennis, May 7, 2015, bit.ly/2fgOmxW.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?