Virgil Thomson Residence at the Chelsea Hotel

overview

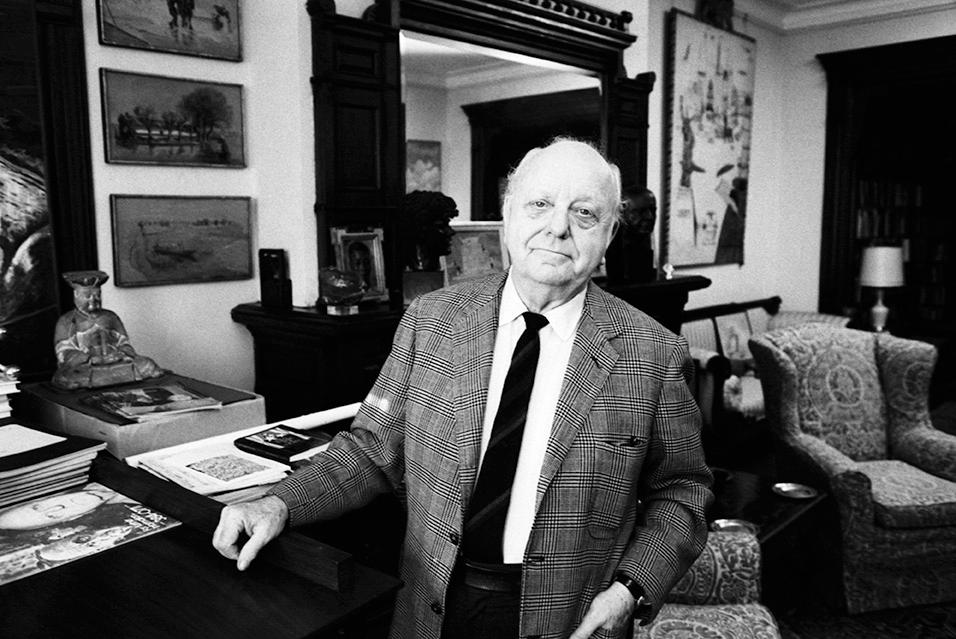

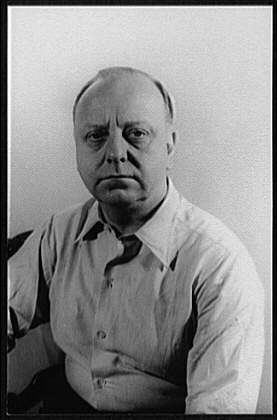

Virgil Thomson, an eminent composer and music critic of the 20th century, cumulatively lived in the Chelsea for over half of his life, staying there from 1936 to 1938 and then from 1940 until his death in 1989.

While here, he served as the chief music critic of the New York Herald Tribune for 14 years, composed over 200 works, and became host and mentor to a salon of LGBT notables in music, art, literature, dance, and theater.

See the Chelsea Hotel and the Stormé DeLarverie Residence at the Chelsea Hotel for more information on this site’s LGBT history.

History

Renowned for his originality and versatility, modernist composer and music critic Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) was a formative figure in the 20th century development of a distinctively American style of classical music.

Thomson first learned to play the piano at five years old while growing up in Kansas City, and, after briefly serving in the National Guard during World War I, he studied composition at Harvard College, touring Europe with the Harvard Glee Club. After graduating in 1923, he privately studied conducting and composition in New York, living at 55 East 34th Street (demolished) in Murray Hill, before moving to Paris in 1925. There, he became involved in the salon of Gertrude Stein and rose to international fame after collaborating with her and artist Maurice Grosser (who was his companion from 1925 until the 1950s) on the groundbreaking opera Four Saints in Three Acts (1928). Featuring an all-Black cast portraying Spanish saints, the opera premiered in 1934 to great fanfare in Hartford, Connecticut, produced by Chick Austin, and then had its Broadway debut two weeks later at the 44th Street Theatre (demolished), with musical direction by Alexander Smallens and choreography by Frederick Ashton.

Thomson regularly visited New York during the 1930s, staying either at the Turtle Bay apartment of architect Philip Johnson or with R. Kirk Askew and his wife Constance in their home at 166 East 61st Street (demolished), where they hosted a salon of notable modernists, many of whom were LGBT. From 1936 to 1938, Thomson stayed at the Chelsea, during which time he composed music for two documentaries, collaborated with Lincoln Kirstein on the ballet Filling Station (1937), and founded Arrow Music Press, a publisher and distributor devoted to American music, with composers Marc Blitzstein, Aaron Copland, and Lehman Engel.

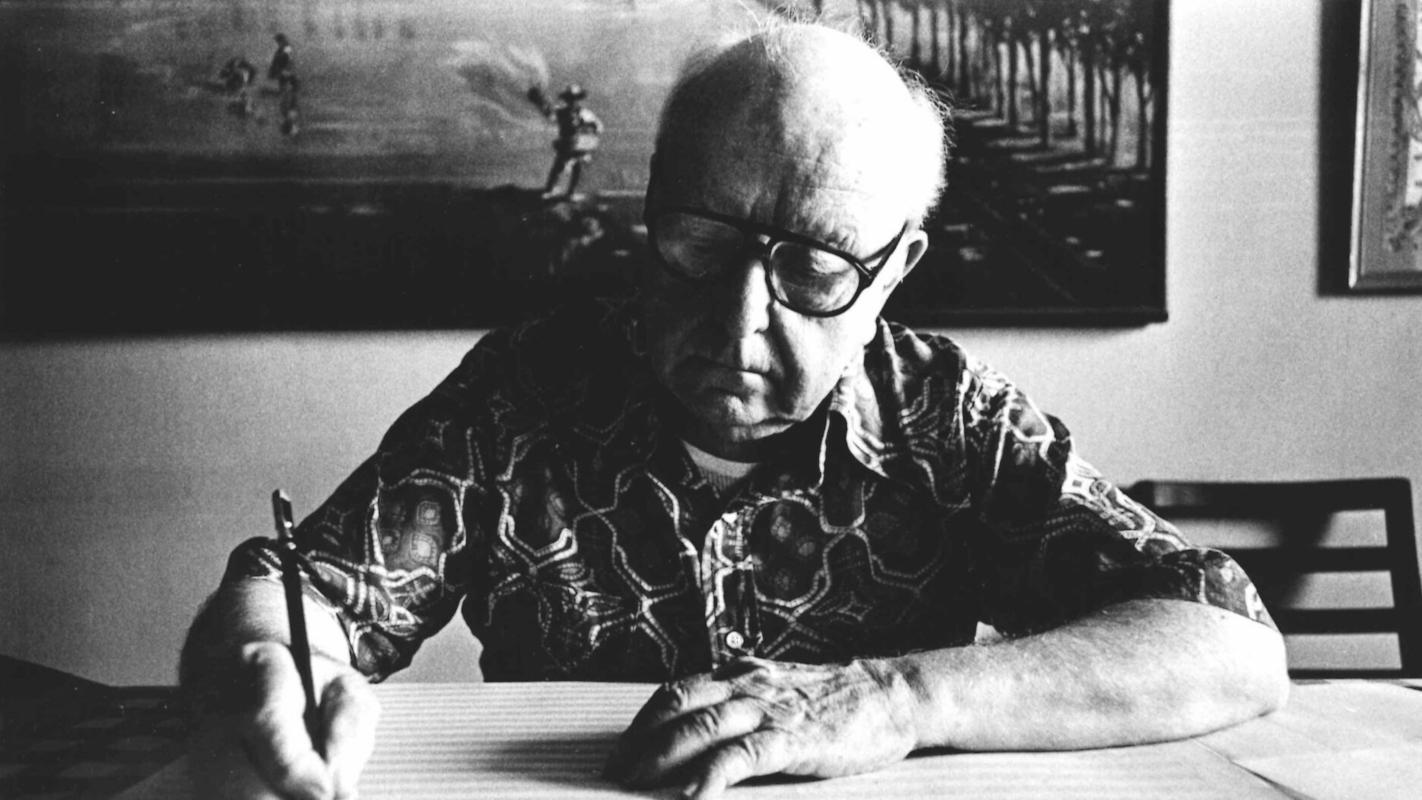

Increasingly regarded as a distinguished critic for his articles in Modern Music and his book The State of Music (1939), Thomson returned to the Chelsea in 1940 and became the chief music critic of the New York Herald Tribune, a position he held until resigning in 1954 “to devote more time to composition.” In 1943, Thomson moved from his small rental room to suite 9C, where he would live until his death. The three-room suite, as described by one of Thomson’s mentees and his posthumous biographer, music critic Anthony Carl Tommasini, included a “spacious salon with rosewood paneling, a closetless bedroom, and a rectangular connecting room that functioned both as office and as dining area.” Adorning the walls were paintings by Grosser, Christian Bérard, Max Jacob, Pavel Tchelitchew, and other friends from Paris.

Although Thomson was incredibly private about identifying as queer (the only term he ever used)—especially after being among those arrested in the 1942 scandal at Gustave Beekman’s gay brothel at 329 Pacific Street in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn—he surrounded himself with other LGBT individuals as friends, collaborators, mentees, and personal secretaries. In his apartment, Thomson regularly hosted legendary dinner parties for a predominantly gay coterie of notable figures in the arts, among them Edward Albee, W.H. Auden, Pierre Boulez, Christopher Cox, Morris Golde, Peggy Guggenheim, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, Philip Johnson, Frank O’Hara, Ben Weber, and Tennessee Williams. He also served as a mentor, paternal figure, and inspiration to the next generation of gay composers, including Leonard Bernstein, Paul Bowles, Gerald Busby, John Cage, Lou Harrison, and Ned Rorem, who worked in Thomson’s dining room as his secretary and copyist. Musicologist Nadine Hubbs has written that Thomson and his circle created a tonal American sound that came to be identified with American culture, in contrast to the straight atonal composers of the time.

While living at the Chelsea, Thomson composed over 200 works, including dozens of innovative “piano portraits” in which these friends would silently sit, as a subject would for a painter, in his living room as he depicted what he called “the sitter’s presence.” He also composed a second opera with Stein, The Mother of Us All (1947), which focused on Susan B. Anthony’s role in the women’s suffrage movement; the Jack Larson opera Lord Byron (1968), which was conducted by Gerhard Samuel and choreographed by Alvin Ailey for its 1972 premiere at Juilliard; and the Pulitzer Prize-winning score for the film Louisiana Story (1948).

In his later years, Thomson’s worsening deafness forced him to focus more on writing than composition. Although, as a critic, his writing was often laden with generalizations, self-promotion, and conflicts of interest, “Thomson’s wit, fire, and prescience outweigh his flaws,” says New Yorker music critic Alex Ross. “He was a formidable player in his historical moment and his moment reverberates into our own.”

Throughout his life, Thomson received various awards, including the Handel Medallion, the Edward MacDowell Medal, the Kennedy Center Honors, and the National Medal of Arts, and was inducted into France’s Legion d’Honneur. He died in his suite in 1989, and his memorial service was held at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in Morningside Heights, Manhattan.

Entry by Ethan Brown, project consultant (October 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Hubert, Pirrson & Company

- Year Built: 1883

Sources

Alex Ross, “The Happy Infamy of Virgil Thomson,” The New Yorker, December 4, 2014 (accessed September 20, 2022), bit.ly/3CdUmDC.

Anthony Tommasini, “An Essential Music Critic, but Nobody’s Role Model,” The New York Times, July 29, 2016 (accessed September 2, 2022), nyti.ms/3RhXJhj.

Anthony Tommasini, Virgil Thomson: Composer on the Aisle (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997).

“Biography,” Virgil Thomson Foundation (accessed August 14, 2022), bit.ly/3AlnjwF.

John Rockwell, “Virgil Thomson, Composer, Critic and Collaborator With Stein, Dies at 92,” The New York Times, October 1, 1989 (accessed September 1, 2022), nyti.ms/3rb67oe.

Moira Hodgson, “Virgil Thomson Orchestrates a Meal And Reminisces,” The New York Times, October 29, 1980 (accessed September 18, 2022), nyti.ms/3LMcYOf.

Nadine Hubbs, The Queer Composition of America’s Sound: Gay Modernists, American Music, and National Identity (Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2004).

Paul Wittke, Virgil Thomson: Vignettes of His Life and Times (New York: Virgil Thomson Foundation, 1996).

“Virgil Thomson Resigns,” The New York Times, July 28, 1954 (accessed ), nyti.ms/3dT87yh.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?