overview

From June 28 to July 3, 1969, LGBT patrons of the Stonewall Inn and members of the local community took the unusual action of fighting back during a routine police raid at the bar.

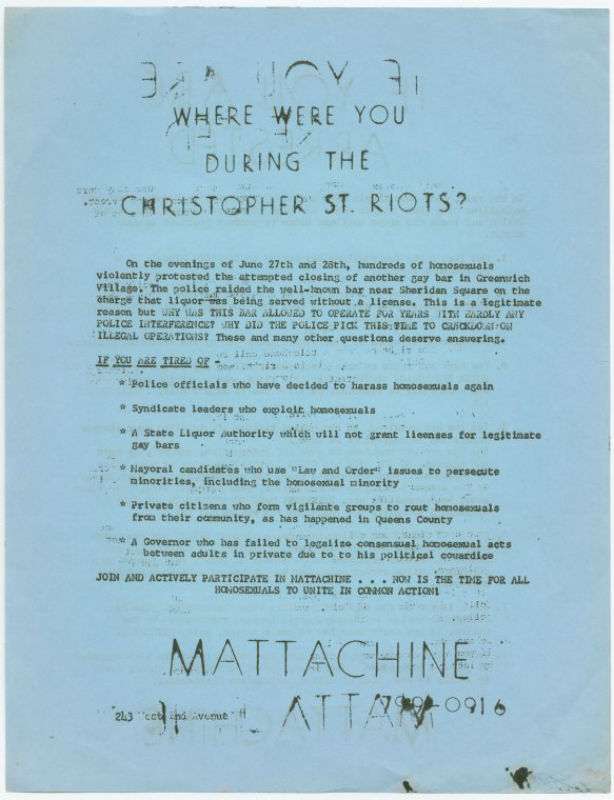

The events during that six-day period are seen as a key turning point and a catalyst for explosive growth in a gay rights movement that began in the United States in 1950 with the founding of the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles. In the immediate aftermath, large numbers of groups formed around the country and thousands of people joined the movement.

Stonewall became the first LGBT site in the country to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places (1999) and named a National Historic Landmark (2000). The site was designated a New York City Landmark in 2015, a State Historic Site in 2016, and as part of Stonewall National Monument in 2016.

History

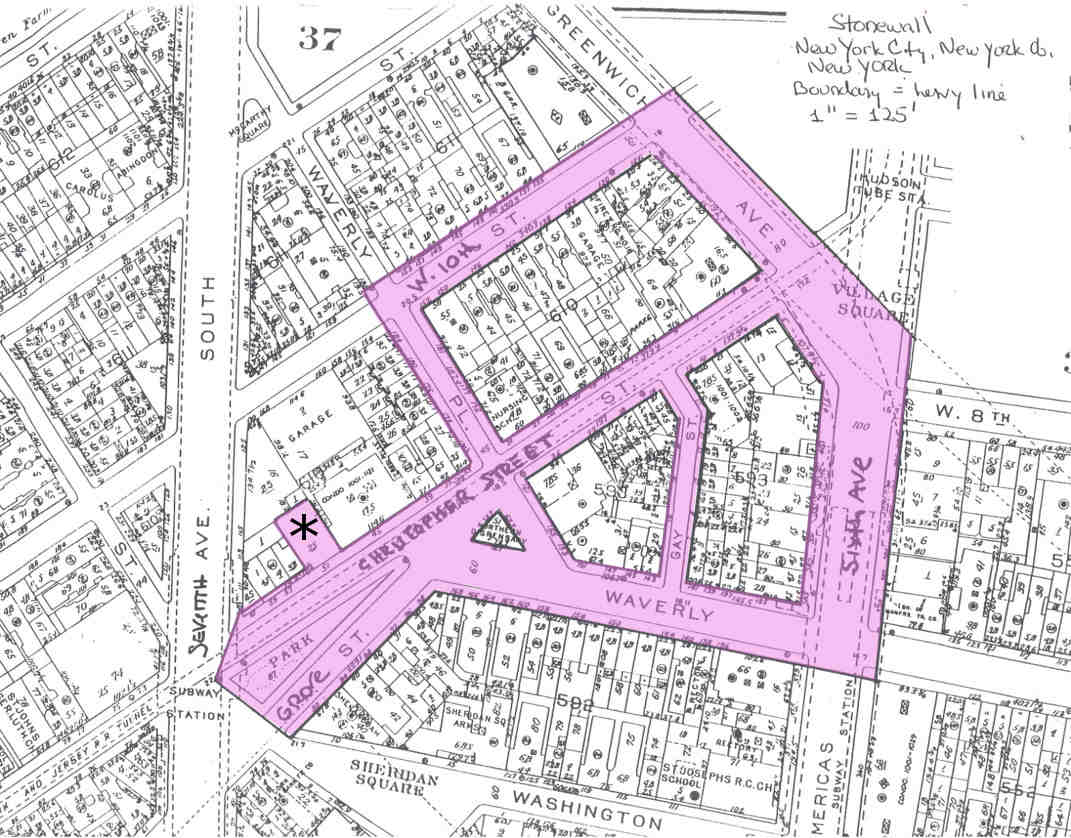

From June 28 to July 3, 1969, the Stonewall uprising that began inside the Stonewall Inn, which occupied the two storefronts at 51-53 Christopher Street, spread outside across the street in Christopher Park, and on several surrounding streets. The event is credited as a key turning point in the LGBT rights movement.

[Stonewall was] the shot heard round the world…crucial because it sounded the rally for the movement.

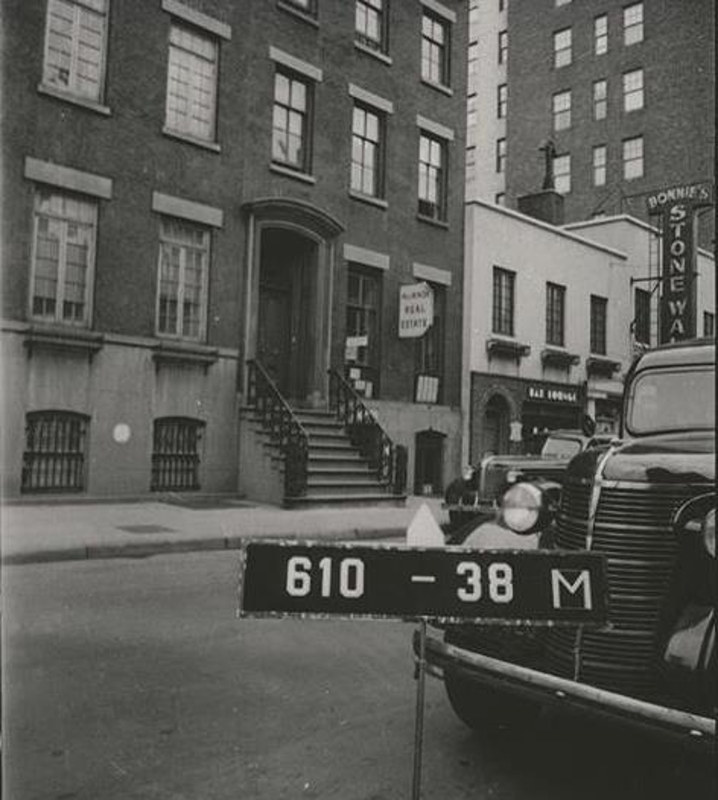

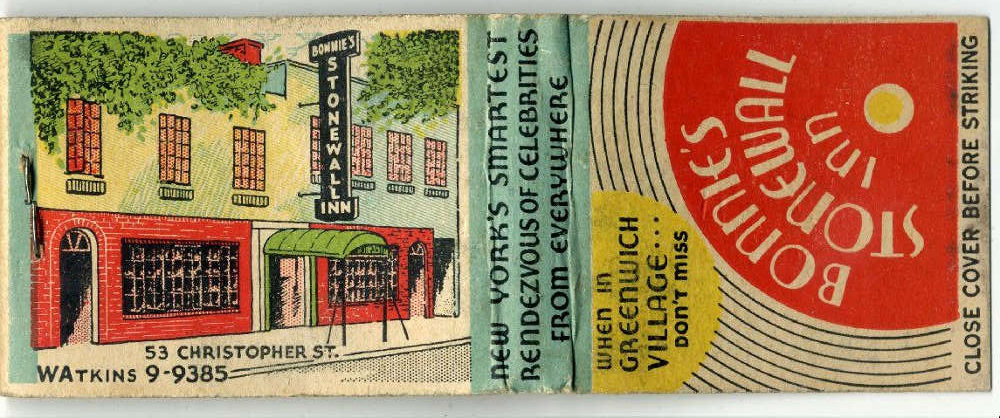

The two buildings were constructed as stables in the mid-19th century. In 1930, they were combined with one façade to house a bakery. In 1934, Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn opened here as a popular Greenwich Village bar and restaurant, and operated until 1964, when the interior was destroyed by fire. In March 1965, the estate that had owned the property for over 150 years sold it, along with five adjacent properties, to Burt and Lucille Handelsman, who were wealthy real estate investors.

The original Stonewall Inn was a gay bar that, like virtually all gay bars since the 1930s, was operated by, or with some, Mafia involvement. Starting in 1934, after the end of Prohibition, the New York State Liquor Authority regulated liquor licenses, which prohibited the serving of alcohol in “disorderly” establishments. The presence of gay people was considered de facto disorderly. This led to routine police raids of gay bars and clubs. Law enforcement would selectively arrest patrons and managers, impound the cash register and alcohol, and padlock the front door. Management typically bribed the police, Mafia, and State Liquor Authority officials for protection, so they were tipped off in advance of an imminent raid and would sometimes turn up the lights to warn patrons to stop any open displays of affection or slow dancing, which could risk arrest.

The Stonewall Inn was opened in 1967 by Mafioso Fat Tony Lauria as a “private” gay club. Gay bars often operated as “private” clubs to circumvent the State Liquor Authority policy that prohibited gay people from being served alcoholic beverages. Beyond the front door, which was located in the 53 Christopher Street building, one entered a small vestibule. To get in, one had to get past a bouncer, pay an entry fee ($1 on weekdays and $3 on weekends), and sign a club register. It was common for people to sign in with joke names such as Judy Garland or Donald Duck. To the left was a coat check and to the right, through a doorway into the 51 Christopher Street building, was a long rectangular room. On the right side of the room was a long bar and beyond that was a dance floor and a jukebox. Opposite the bar was a small entrance back into 53 Christopher where there was a second dance floor, with a jukebox and a small bar at the rear, which was adjacent to two bathrooms. The Stonewall’s interior was painted black as a quick and inexpensive way to mask the fire damage the space sustained in 1964. The large front windows were painted black and backed by plywood. The Stonewall Inn’s main bar had no running water and there were no fire exits.

The Stonewall was one of the few gay bars in Greenwich Village where patrons could dance. It drew a diverse, young clientele, as well as a small number of lesbians. Some patrons dressed in various forms of drag, and there were also people who wore business attire or jeans and flannel shirts.

Stonewall was like Noah’s ark. There was [sic] two of everything.

The Uprising

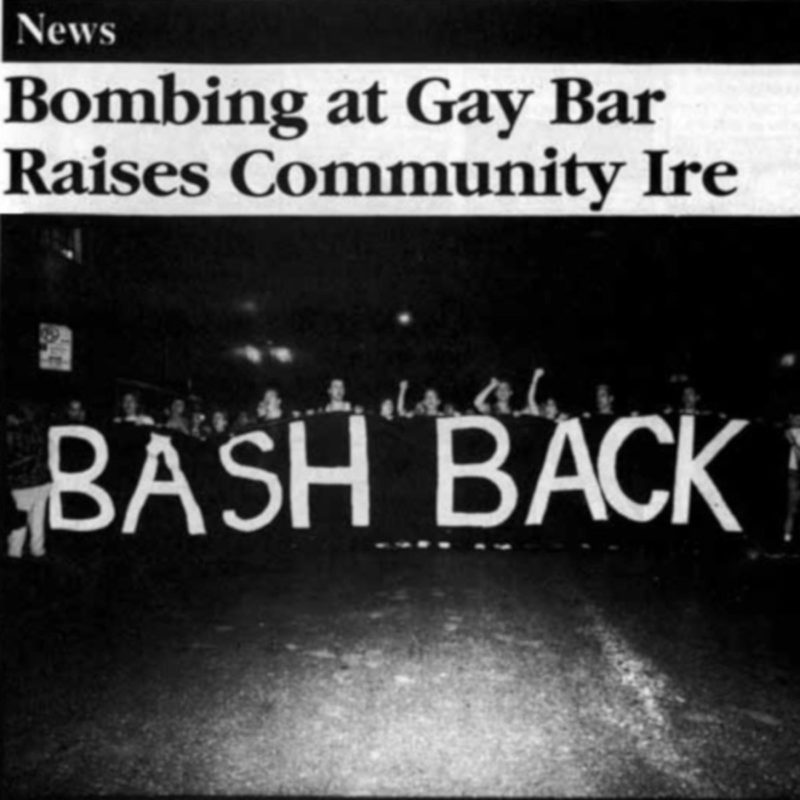

In the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, bar patrons decided to take a stand. What started out as an all-too-routine police raid, led by NYPD Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, of the Stonewall Inn turned into a multi-night uprising on the streets of Greenwich Village. It was not the first time LGBT people fought back and organized against oppression, but the Stonewall uprising ignited a mass movement that quickly spread across the United States and around the globe. In addition to routine police raids of gay bars around the country where many arrests occurred, there were several previous, well-documented confrontations between LGBT people and the police. These included ones at Cooper Do-Nuts in Los Angeles in 1959; a fundraiser for the Council on Religion and the Homosexual in San Francisco in 1965; a Dewey’s restaurant in Philadelphia, also in 1965; San Francisco’s Compton’s Cafeteria in 1966; and the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles in 1967.

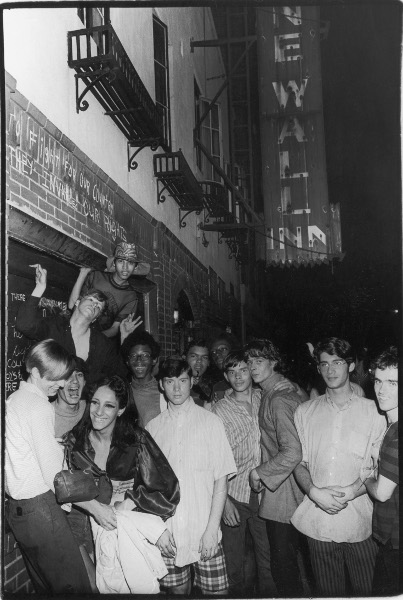

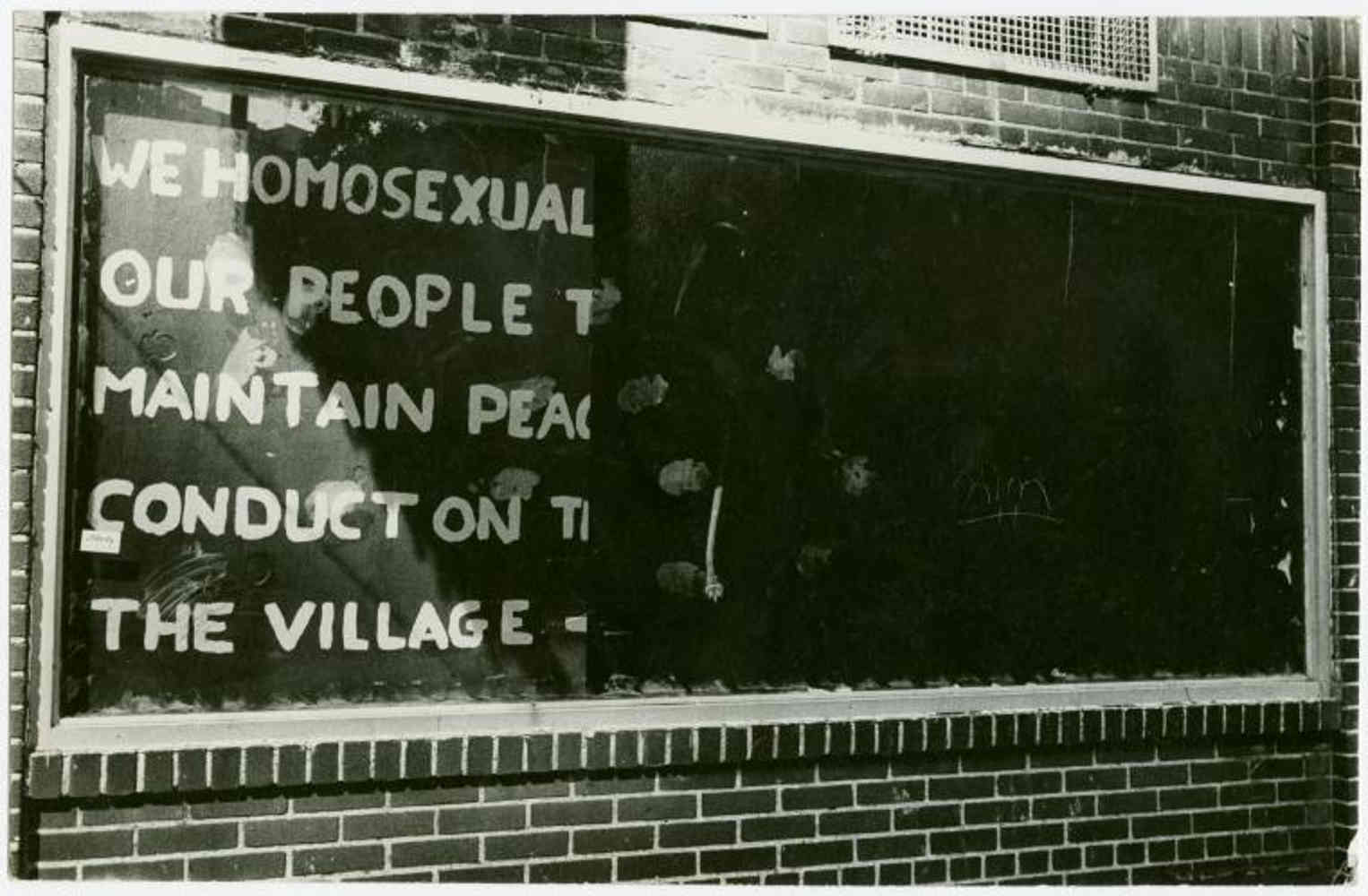

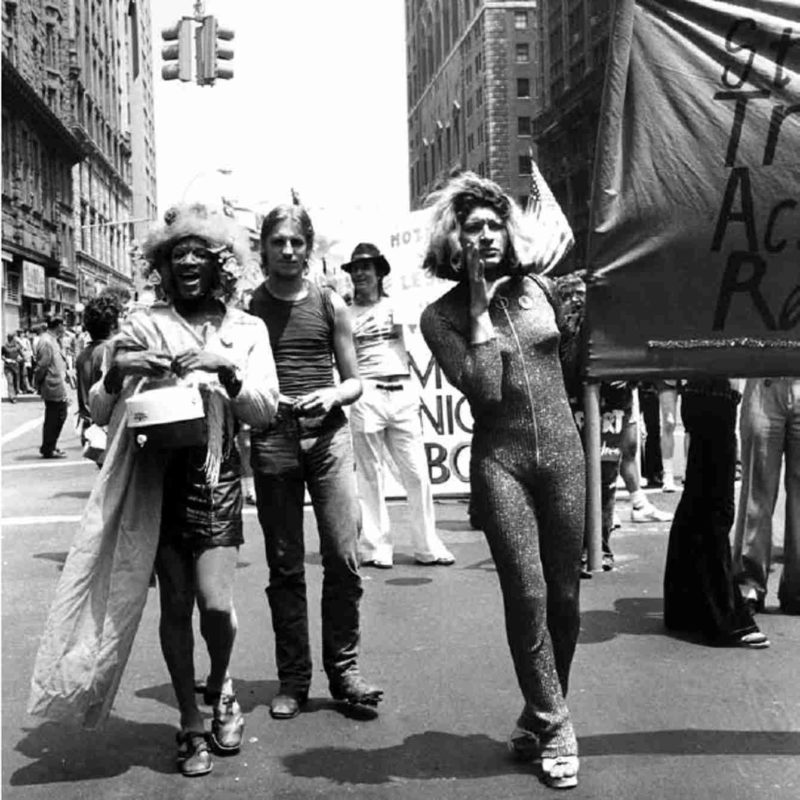

The unusual reaction of the Stonewall’s patrons spurred the crowd outside, which came to include a diverse segment of the local LGBT community – homeless LGBT teens, trans women of color, lesbians, drag queens, and gay men – as well as other residents of Greenwich Village and visitors. Instead of dispersing, the angry crowd began to fight back as bar patrons were arrested, throwing beer cans and other objects at the police who were forced back into the bar. A number of eyewitnesses have offered differing accounts, but, as with almost any riot or spontaneous confrontation with the police, no one knows for certain what exactly sparked the confrontation or who threw the first punch or object. Even before the 1969 Stonewall uprising, Christopher Park was a favorite hangout for a diverse group of (often homeless) gay street youth and those who might identify today as queer, transgender, or non-binary.

The demonstrations continued over the next few nights outside the Stonewall Inn, in Christopher Park, and along adjacent streets between Seventh Avenue South and Greenwich Avenue, with the most intense clashes occurring on the first and sixth nights. Accounts vary, but according to eyewitnesses the first night brought out five to six hundred people, the second night about two thousand, and the sixth and final night five hundred to a thousand. The third and fourth nights were relatively quiet. On the first night of the uprising 13 arrests were made, on the second night three, and on the sixth night five. There were no fatalities among the rioters or the police, although on the second night a group of protestors swarmed a cab on Christopher Street, rocked it back and forth, and the driver died later that night from an apparent heart attack. What took place at the Stonewall Inn is variously described as a riot, uprising, rebellion, or all three. A handful of Greenwich Village shops were looted on the final night of the uprising.

There is no film or video footage of the Stonewall uprising. There is one photo from the first night taken by Daily News photographer Joseph Ambrosini and four photos of Stonewall uprising participants from the second night taken by noted Village Voice photographer Fred W. McDarrah. There are several photographs of the damaged interior taken by McDarrah, and exterior photos taken right after the uprising by Diana Davies. Larry Morris with the New York Times took a number of photographs of groups of people on the streets on the sixth and final night of the disturbances.

After Stonewall

The uprising was a key turning point and a catalyst for explosive growth in a movement that began in the United States in 1950 with the founding of the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles. (The first gay rights organization in the world was founded in 1897 in Berlin by Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld and the first, short-lived American organization, the Society for Human Rights, was founded in 1924 in Chicago by Henry Gerber.) The struggle for LGBT rights did not actually begin at Stonewall, as a number of groups in New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and other cities had already been organizing and demonstrating for their equal rights. Prior to the Stonewall uprising the gay rights organizations in the nation’s major cities had a modest number of members. In the aftermath of Stonewall and in the years that followed, organizers of new LGBT civil rights organizations across the country and around the world drew hundreds of thousands of activists into the fight for equal rights.

By the time of Stonewall, we had fifty to sixty gay groups in the country. A year later there was at least fifteen hundred. By two years later, to the extent that a count could be made, it was twenty-five hundred. And that was the impact of Stonewall.

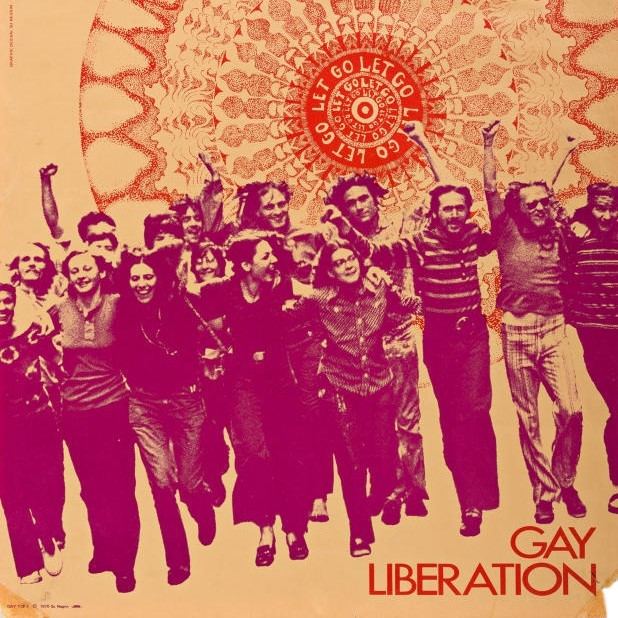

In addition, the Stonewall rebellion sparked the next major phase of the gay liberation movement, which involved more radical political action and assertiveness during the 1970s. Groups such as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), Radicalesbians, and the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) were organized within months of Stonewall. Since Stonewall occurred in the media capital of the U.S. and took place over multiple days, it attracted more attention than previous confrontations. At the one-year anniversary, the first annual Christopher Street Liberation Day March (later known as the Gay Pride March and then the LGBT Pride March) took place in New York, with similar events in other cities in the United States; the number of marches expanded internationally over the next few years. The annual March contributed greatly to solidifying the significance of Stonewall in LGBT history.

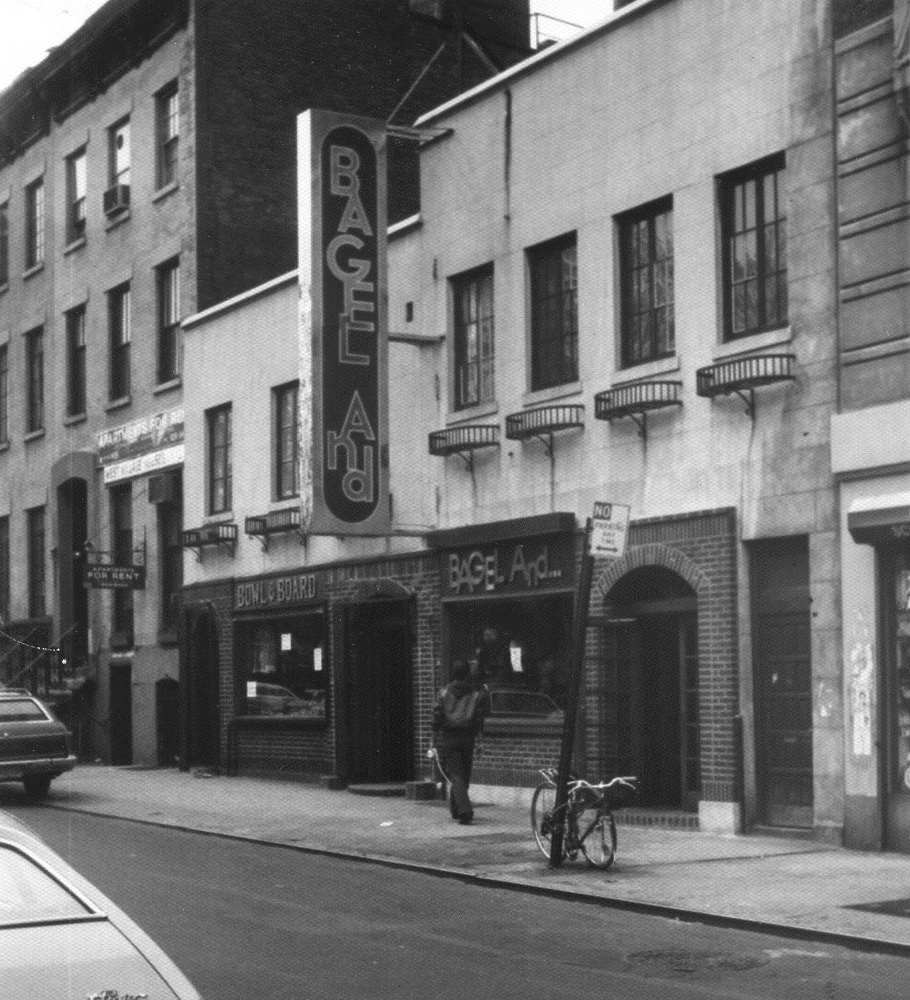

The Stonewall Inn went out of business shortly after the uprising and was leased as two separate spaces to a number of different businesses over the years, including a bagel shop, Chinese restaurant, and clothing store. From 1987 through 1989, a bar named Stonewall operated out of 51 Christopher Street. When it closed, the historic vertical sign was removed from the building’s façade. None of the original Stonewall Inn’s interior finishes remain.

In 1990, 53 Christopher Street was leased to a new bar named New Jimmy’s at Stonewall Place and about a year later the bar’s owner changed the name to Stonewall. The current management bought the bar in 2006 and has operated it as the Stonewall Inn ever since. The buildings at 51 and 53 Christopher Street are privately owned. The building’s existing 50-foot-wide façade looks much as it did at the time of the uprising in 1969.

In 1989, in honor of the 20th anniversary of the uprising, the section of Christopher Street in front of the Stonewall Inn was renamed Stonewall Place. The importance of Stonewall was further recognized with the installation of George Segal’s sculpture Gay Liberation in Christopher Park in 1992.

Today, LGBT people, tourists, and allies from around the world continue to visit Stonewall and recognize it as a major symbol of civil rights, solidarity, and remembrance. For example, on June 26, 2015, a large crowd gathered in celebration here after the United States Supreme Court declared state bans on same-sex marriage unconstitutional. A year later, people mourning the victims of the June 12, 2016, mass shooting at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, left flowers and messages on the sidewalk in front of Stonewall.

Landmark Designations for LGBT Significance

Andrew S. Dolkart, Ken Lustbader, and Jay Shockley, the three founders of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, have been involved in preservation efforts around Stonewall since the early 1990s. In 1992, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission’s (LPC) first edition of Guide to New York City Landmarks was written by Dolkart. The book included two LGBT mentions, one of which was the Stonewall Inn, making them the LPC’s earliest explicit acknowledgement of LGBT sites.

The buildings and/or the surrounding area have been officially recognized on the city, state and federal levels. Stonewall became the first LGBT site in the country to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places (1999) and named a National Historic Landmark (2000). The nomination, available in the “Read More” section below, was written by Dolkart, with Shockley, using, in part, research from David Carter (who published his Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution book in 2004).

Stonewall was later designated a New York City Landmark by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2015, a New York State Historic Site by Governor Andrew Cuomo in 2016, and a National Monument by President Barack Obama in 2016, which included advocacy efforts by Lustbader.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, Jay Shockley, and Ken Lustbader, project directors (March 2017; last revised June 2021).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: William Bayard Willis (1930 alteration)

- Year Built: 1930, two existing buildings combined with one façade

Sources

Christopher D. Brazee, Corrine Engelbert, and Gale Harris, Stonewall Inn Designation Report (New York: Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2015).

David Carter, Andrew Scott Dolkart, Gale Harris, and Jay Shockley, “Stonewall,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (New York, January 1999).

David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004).

Franklin Kameny, “Stonewall: Myth, Magic and Mobilization,” Public Radio International, 1994. [source of pull quote]

Fred W. McDarrah and Timothy S. McDarrah, Gay Pride: Photographs from Stonewall to Today (New York: A Capella Books, 1994).

Lillian Faderman, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Penguin, 1991). [source of Faderman quote, p. 195]

Martin Duberman, Stonewall (New York: Dutton, 1993).

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, Making Gay History, New York Public Library, GLSEN, National Parks Conservation Association, and the Stonewall 50 Consortium, Stonewall: The Basics, 2019, bit.ly/3ueDLZu.

Read More

- National Register of Historic Places Nomination (1999)

- National Historic Landmark Nomination (2000)

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission Designation Report (2015)

- Stonewall National Monument (2016)

- Stonewall: The Basics (2019)

- Stonewall: Lo Básico (en español) (2019)

- Marching for Pride: The Basics (2020)

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?