St. Vincent’s Hospital Manhattan

overview

Beginning in the early 1980s, under the leadership of the Sisters of Charity, an organization within the Catholic Church, St. Vincent’s Hospital was “ground zero” of the AIDS epidemic in New York City and housed the first and largest AIDS ward on the East Coast.

It was also the site of numerous LGBT actions against discrimination and violence as early as 1970. Nearby is the New York City AIDS Memorial, dedicated in 2016.

History

Founded in 1849 by the Sisters of Charity of New York, an organization within the Catholic Church, the former St. Vincent’s Hospital Manhattan operated in Greenwich Village for over 160 years until it declared bankruptcy and closed in 2010. At that time, the hospital complex consisted of nine buildings, constructed between the 1920s and 1980s.

St. Vincent’s was founded as one of the few charity hospitals in the city with a mission to serve the poor and disenfranchised, often regardless of their ability to pay. (The middle name of one-time Greenwich Village resident, Edna St. Vincent Millay, derives from the hospital, where her uncle’s life was saved before her birth.) The surrounding neighborhood emerged as an LGBT enclave in the early 20th century when it began attracting a significant number of LGBT people, establishments, and organizations. In the 1980s, St. Vincent’s was the hospital in New York City most closely associated with the AIDS epidemic and was considered to be the national epicenter of AIDS.

Beginning in 1981, the emergency room at St. Vincent’s (demolished) witnessed large numbers of acutely ill young gay and bisexual men exhibiting unexplained weight loss, rare infections, pneumonia, and/or signs of compromised immune systems. By the time HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, was first identified in 1983, St. Vincent’s had become the epicenter of the epidemic in New York City with patients overwhelming the emergency room, its hallways, and beds. At that time, it was one of the few hospitals in the city that did not turn away people with HIV or AIDS, even though many of its policies were grounded in Roman Catholic doctrine (i.e., anti-LGBT and against the distribution of condoms) and many administrators and physicians were felt to be homophobic. Over time, attitudes and policies changed, much to the credit of the Sisters of Charity who cared for patients. Up until it closed in 2010, thousands of the more than 100,000 New Yorkers who had died of complications from AIDS were treated or died at St. Vincent’s.

In 1984, in response to the growing epidemic, the hospital opened the first and largest AIDS ward on the East Coast. The concept of a hospital floor exclusively dedicated to AIDS patients was modeled after San Francisco General’s Ward 86, which opened in 1983. That same year in New York City, the Community Health Project (CHP) – today’s Callen-Lorde Community Health Center – began operating from the LGBT Community Center as the nation’s first community-based HIV clinic, which had a significant number of St. Vincent’s staff as volunteers. CHP was, however, the result of a merger between the older counter–cultural St. Mark’s Community Clinic and the Gay Men’s Health Project, whose clinic, founded in 1972 at Liberation House, was the first for gay men on the East Coast. As the need for AIDS care increased in New York, in 1985, St. Clare’s Hospital (426 West 52nd Street) responded by opening specialized wards for AIDS and, by 1987, the entire facility was transformed into the state’s first all-AIDS treatment facility.

By 1986, more than half of St. Vincent’s 650 hospital beds were occupied by AIDS patients and, three years later, it was deemed one of the city’s first Designated AIDS Centers by the New York State Department of Health/AIDS Institute. To meet the demands of outpatient care and research, the hospital opened its Comprehensive HIV Center in its O’Toole Building (extant) on Seventh Avenue between 12th and 13th Streets in 1988. (O’Toole was built as the National Maritime Union Headquarters and sold to St. Vincent’s in 1973. It is the only building in the complex not constructed for the hospital.) When HIV-related deaths peaked by 1995, the hospital had become one of the nation’s largest HIV treatment centers offering HIV primary care, co-located specialty care, coordinated inpatient and outpatient services, an onsite pharmacy, and access to the latest AIDS medications through a variety of clinical trials.

Hospital administrators initially located the AIDS ward on the seventh floor of Spellman (facade extant), an older building with small rooms for single beds. As the patient load increased, patient beds in Spellman were doubled up and the ward was expanded to the seventh floor of the interconnected, and more up-to-date, Cronin Building (demolished), which became the primary unit. At the height of the epidemic, once the ward was at capacity, the medical team located patients throughout the complex as needed through the creation of a scatter bed program.

Many medical professionals, patients, lovers, friends, and family members had ambivalent feelings towards St. Vincent’s, remembered as much for its excellent and appreciated team of healthcare workers and staff as for its homophobic policies and overwhelming loss of life. Over time, the policies of the hospital changed to keep pace with the epidemic and new information about transmission and treatment.

The AIDS ward was a unique part of the hospital where medical professionals flexed hospital rules, thereby allowing patients to have privacy (and reportedly sex) with lovers, unsanctioned parties, and drop-in visits by friends and family without adhering to regular hours. In one instance, a patient unsuccessfully attempted to have the annual Greenwich Village Halloween Parade diverted to the AIDS unit. To console his disappointment, one of the nuns allowed him to wear her habit for the day.

Once you came into the ward, it was like you stepped into another place. There was warmth and love and compassion. The nun who ran the unit – Sister Patricia – was full of love. It was full all the time. Every day we admitted fevers, fevers, fevers…[and] they had all these terrible infections. It was really kind of a hospice. But outside that unit, you were in trouble.

Matt Baney, Director of the AIDS Program at St. Vincent’s between 1991 and 2000, noted that “The nuns wouldn’t allow anyone to work on the floors that demonstrated homophobic actions towards a patient.” In the early 1990s, in response to the impact of AIDS on all ages from pediatrics to geriatrics, it created a family-centered program to address newborns, children, and adolescents infected or affected by HIV and worked with other organizations to assist in placing children orphaned by HIV.

St. Vincent’s, and the AIDS ward, was prominently featured in both Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart (1985) and Tony Kushner’s Angels in America (1993).

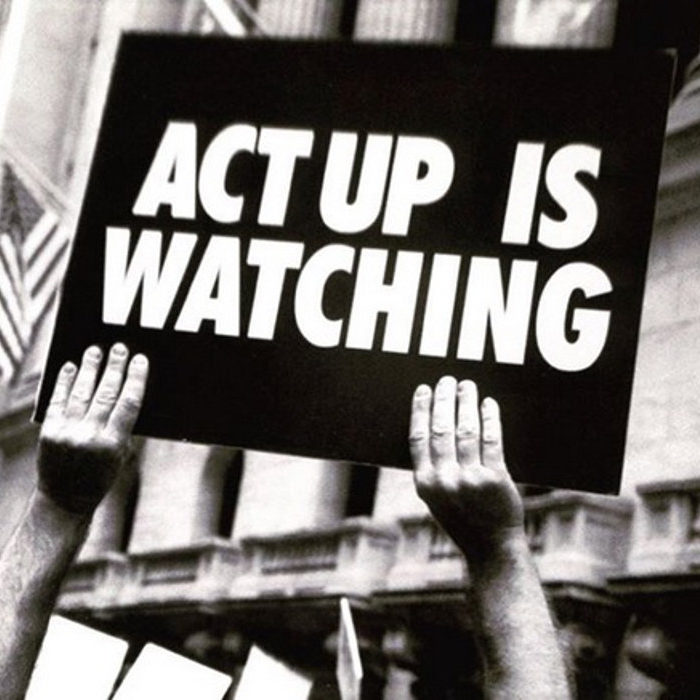

St. Vincent’s was also the site of AIDS activism by ACT UP, founded nearby at the LGBT Community Center. In 1989, ACT UP stormed the hospital’s emergency room after a man was kicked out for kissing his lover. This action resulted in multiple meetings to get the rule changed and the implementation of sensitivity training. ACT UP, along with other LGBT organizations, also conducted Christmas visits for patients on the ward.

By the late 1990s, a new class of medications and treatments increased the lifespans of people living with HIV/AIDS. Under the leadership of Gabriel Torres, M.D., St. Vincent’s participated in federally and privately funded pharmaceutical studies. St. Vincent’s published findings that showed a decrease in inpatient and outpatient treatment and hospitalizations with protease inhibitors. For the next decade, the AIDS ward continued to operate and by 2007, three years before the hospital’s closure, it only occupied half a floor.

The comprehensive medical AIDS program at St. Vincent’s, as well as other AIDS Centers in the city, were the basis for the future population health initiatives currently operating throughout the country. At the time of its closing in 2010, it had one of the oldest HIV centers and most-renowned HIV treatment programs in the country.

By 2010, the hospital had been reduced to approximately 400 inpatient beds. A year later, after Catholic hospital mergers and bankruptcy, the entire nine-building complex was sold to Rudin Management Company for conversion into residential condominiums and townhouses. As part of the conversion, four buildings were demolished. Today, four building facades survive, including the Spellman facade, which housed the AIDS Clinic inpatient program. The O’Toole Building, which housed the outpatient clinic, is extant and continues to operate as a medical facility.

Additional LGBT history at St. Vincent’s

On March 7, 1970, activists from the Gay Activists Alliance, Gay Liberation Front, and other groups held a candlelight vigil at St. Vincent’s for Diego Vinales, who was injured as a result of the raid at the Snake Pit.

On April 28, 1990, three men were treated at St. Vincent’s for injuries sustained after a pipe bomb exploded at Uncle Charlie’s, a nearby gay bar.

New York City AIDS Memorial

The New York City AIDS Memorial Park at St. Vincent’s Triangle, dedicated on World AIDS Day, December 1, 2016, is located at the intersections of Seventh Avenue South, West 12th Street, and Greenwich Avenue. It is on the site of the former St. Vincent’s Materials Handling Center (demolished) where medical supplies and corpses were transported to and from the hospital through tunnels that ran underneath Seventh Avenue.

The design of the Memorial, by Studio a+i, includes a triangular canopy, central fountain, and paving designed by Jenny Holzer with passages from “Song of Myself” (1855) by Walt Whitman. It honors the more than 100,000 New Yorkers who have died of AIDS and recognizes the contributions of caregivers and activists, many affiliated with St. Vincent’s and ACT UP. Its location, at the crossroads of AIDS history, has associations with St. Vincent’s, the LGBT Community Center, where ACT UP and other AIDS advocacy and support groups first organized, and the LGBT neighborhoods of Greenwich Village and Chelsea.

Entry by Ken Lustbader, project director (February 2021).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: I.E. Ditmars (Nurses Residence); Crow, Lewis, and Wick (Spellman Building); Eggers & Higgins (Smith/Raskob); Eggers & Higgins (Reiss Pavilion); Arthur A. Schiller & Albert Ledner (National Maritime Union Headquarters; renamed the O’Toole Building in 1973 when it was sold to St. Vincent’s)

- Year Built: 1924 (Nurses Residence); 1941 (Spellman Building); 1946/1950 (Smith/Raskob); 1953 (Reiss Pavilion); 1963 (National Maritime Union Headquarters; renamed the O’Toole Building in 1973 when it was sold to St. Vincent’s)

Sources

Alexandra Schwartz, “New York’s Necessary New AIDS Memorial,” The New Yorker, December 8, 2016 (accessed January 21, 2021), bit.ly/3sNvwUH.

Andrew Boynton, “Remembering St. Vincent’s,” The New Yorker, May 16, 2013 (accessed January 21, 2021), bit.ly/36iWDNR.

David E. Pitt, “AIDS Helps Rescue Ailing Hospital,” The New York Times, November 22, 1987 (accessed January 26, 2021), nyti.ms/2KSyJRG.

E-mails with Antonio E. Urbina, MD to Ken Lustbader/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, January 2019 and January/February 2021.

E-mails with Matthew Baney to Ken Lustbader/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, January 2019 and January/February 2021.

Michael J. O’Loughlin, “The Secret History of Catholic Caregivers and the AIDS Epidemic,” America – The Jesuit Review, June 10, 2019 (accessed February 1, 2021), bit.ly/3amsQF9.

New York City AIDS Memorial website (accessed January 21, 2021), bit.ly/3iAvvP8.

“St. Vincent’s Remembered,” Out, August 17, 2010 (accessed January 21, 2021), bit.ly/3p0UAVP. [source of George quote]

Sinead MacCloud, “Life & Death at St. Vincent’s Hospital,” Researching Greenwich Village History, January 12, 2015 (accessed January 21, 2021), bit.ly/361mBFi.

Tom Eubanks, Ghosts of St. Vincent’s (New York: Tomus, NYC, 2017).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?