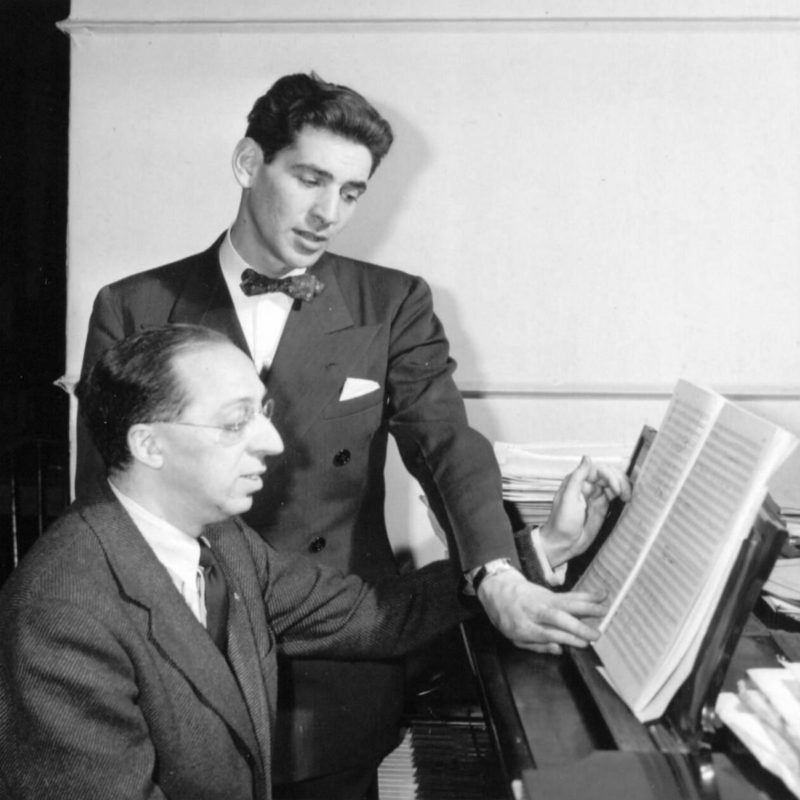

Silence = Death Collective at Jorge Socarrás Residence

overview

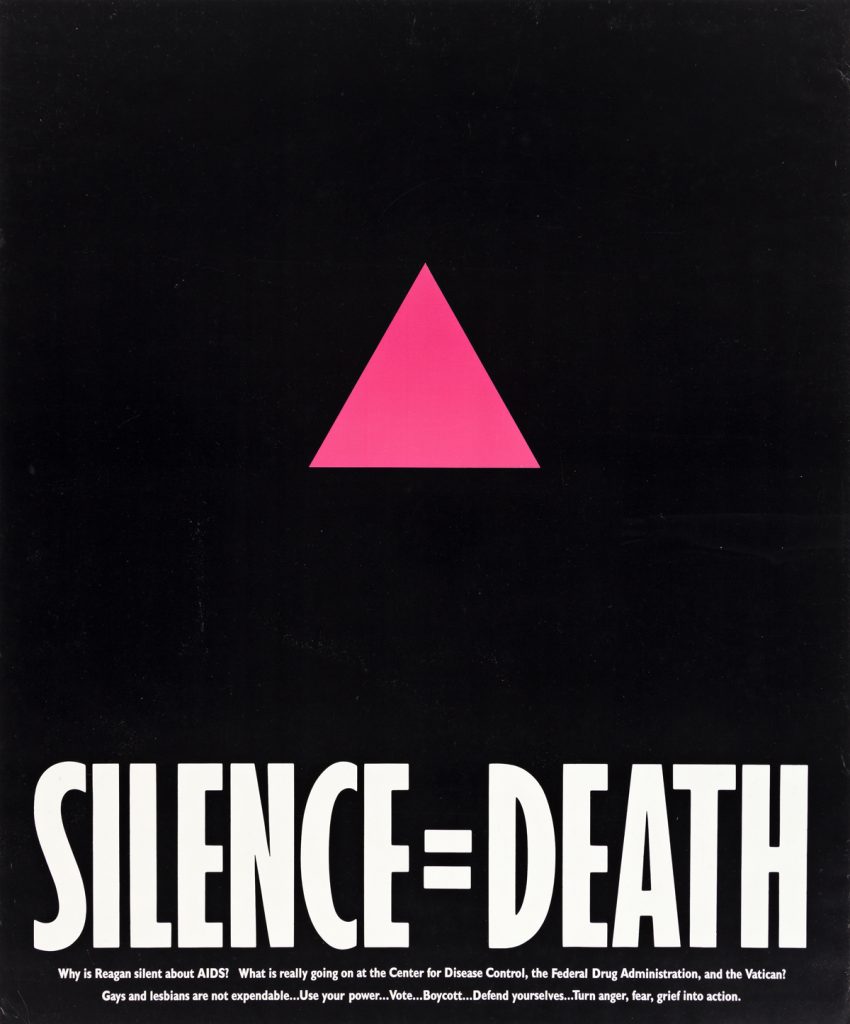

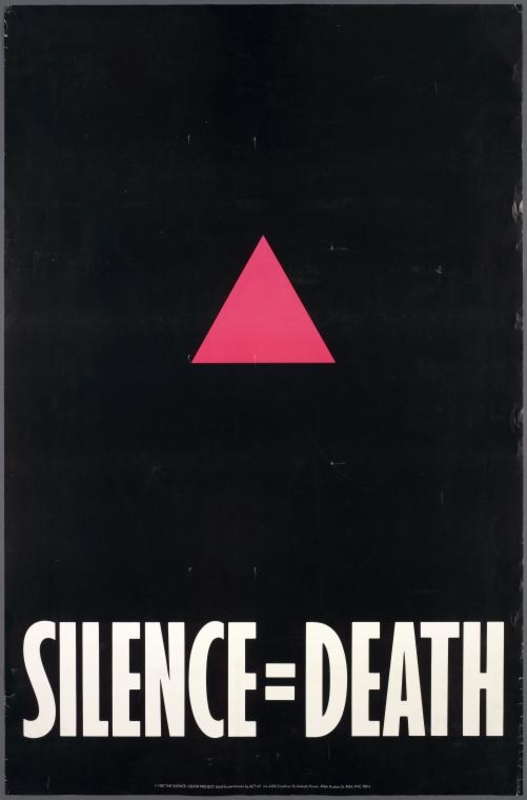

In December 1986, at the East Village apartment of musician Jorge Socarrás, a political collective of six gay artists finalized its now-iconic Silence = Death poster, featuring the pink triangle, which they designed in response to the AIDS epidemic.

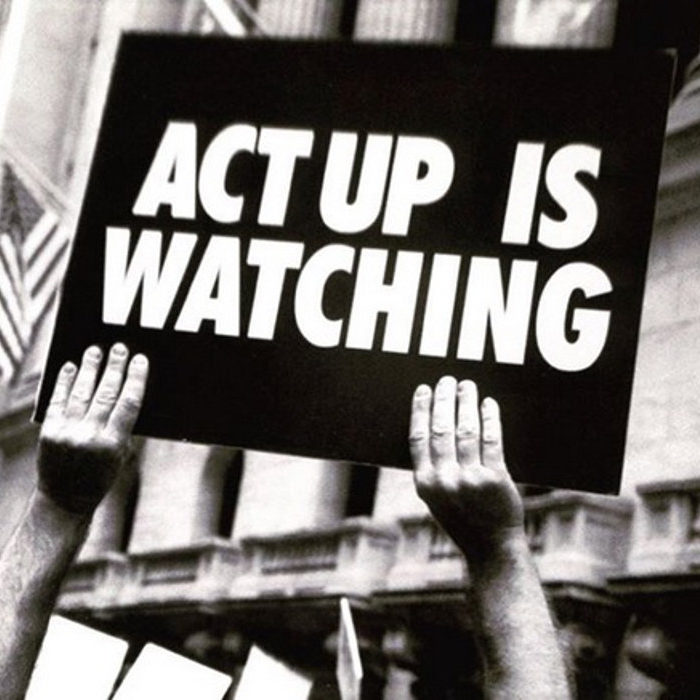

The Silence = Death collective, as they became known, ultimately gave permission to ACT UP to use the poster in its demonstrations and outreach, making the design one of the most influential works of protest art in American history.

History

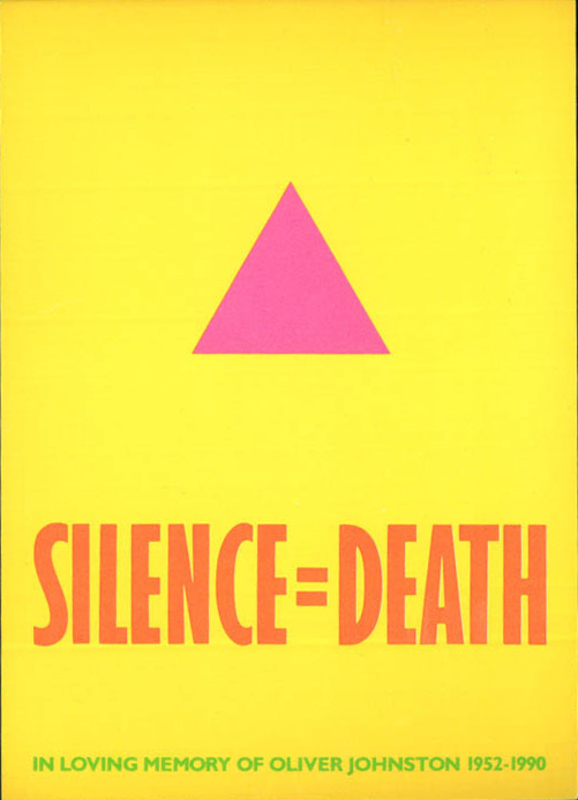

At the end of 1985, art director Avram Finkelstein, graphic designer Oliver Johnston, and musician Jorge Socarrás, all in their early 30s, decided to form what would become a consciousness-raising group in response to the AIDS epidemic. Their motivation was deeply personal. Finkelstein’s partner Don Yowell died a year earlier from AIDS-related complications and Socarrás had lost so many lovers and friends to the disease that he stopped writing down their names once the list reached 100. (Johnston, diagnosed with HIV in 1986, died of AIDS-related causes in 1990.) Each group member invited a friend, and soon art directors Chris Lione and Charles Kreloff and photo editor Brian Howard joined.

The six artists, forming a political collective, met for weekly potlucks at each other’s apartments. From these came the idea to create a poster to mobilize LGBT people and to counter the nationwide silence over AIDS. Kreloff and Finkelstein remembered how young people in 1960s Greenwich Village used the streets to exchange and post information. In contrast to that highly political decade, however, they felt that a poster for the 1980s called for a less text-heavy approach.

To ‘sell’ activism in an apolitical moment, the poster needed to be cool and to intone ‘knowing’ …. It needed to be advertising.

The poster’s now-iconic tagline, Silence = Death, came into existence in less than a minute, according to Finkelstein, at a December 1986 holiday dinner in Socarrás’s East Village apartment. (Socarrás, born to Cuban parents in New York City, lived at 508 East 5th Street from at least 1985 to 1988.) Finkelstein suggested “Gay Silence is Deafening” based on a phrase from an unrelated New York Times article. Johnston then proposed “Silence is Death,” which someone followed with “Silence Equals Death.” When another suggested using the equal sign instead, the group simultaneously jumped up and shouted so loudly in agreement that Finkelstein was sure people as far as Avenue A could hear them.

On that same evening, the group that became known as the Silence = Death collective (also the Silence = Death Project) agreed that the poster needed a blank and expansive black background. Black was then a popular color in the design field. Finkelstein notes that it also “implied a foreboding storm of political action, and of course, it directly referred to death.” The collective sketched out the poster’s proportions before toasting each other and the poster.

It was in Jorge’s apartment, we were all seated around his table, covered with colored paper, geometric cutouts, glue, tape, pencils …. We had finalized the design of the Silence = Death poster. A sense of excitement, calm, togetherness, fear, strength and of love filled the apartment.

Before that holiday dinner, the pink triangle had been selected, after much debate, as the poster’s image. Recognizing that AIDS also impacted women and people of color, the collective felt that a pictographic image would be the most inclusive choice. The group – half Jewish – was well aware of the Holocaust origins of the pink triangle, which, by the early 1970s, had been controversially reclaimed as a gay pride symbol. Finkelstein writes, “the codes activated by the triangle were open-minded enough to be useful, signifying lesbian and gay identity to some audience members, maleness to others, and referencing the historical meanings of genocide to audiences familiar with that history.” Only after the poster was printed did the collective realize that the triangle mistakenly pointed up rather than down. They decided the change was effective and kept it.

From the last week of February through March 1987, hundreds of Silence = Death posters were wheat-pasted on the temporary plywood walls of construction sites. Placing them next to commercial advertisements on these walls was intentional because it implied a voice of authority and a level of funding and organizing the six-person collective did not actually have. Posters were placed where LGBT people lived and gathered. This included the East Village, lower Broadway, SoHo, Greenwich Village, Chelsea, Hell’s Kitchen, and parts of the Upper West Side. Gay bars, other than Uncle Charlie’s and Boots & Saddle in the Village, largely declined to display the poster out of concern that its AIDS messaging would deter patrons.

The initial response was underwhelming. Soon, however, the Silence = Death poster became one of the most influential works of American protest art through its association with the newly formed group ACT UP. Lione, Johnston, and Finkelstein regularly attended its meetings as founding members and saw its potential to provoke people into action. With the collective’s permission, ACT UP first used the poster at its second demonstration, the Tax Day Action held on April 15, 1987, at the U.S. General Post Office (now the James A. Farley Building) in Manhattan. This and future demonstrations around the world have since turned the Silence = Death imagery into a global symbol synonymous with ACT UP.

The poster is now in several collections, including those of the Brooklyn Museum and the National Museum of American History.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (March 2025).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown

- Year Built: 1859-60

Sources

“AIDSGATE,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, bit.ly/4iUPdTI.

Avram Finkelstein, After Silence: A History of AIDS through Its Images (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018). [source of all Finkelstein quotes, 44-47]

Avram Finkelstein, “The Silence=Death Poster,” blog, The New York Public Library, November 22, 2013, bit.ly/4j4Dz8Y.

James Emmerman, “After Orlando, the Iconic Silence = Death Image Is Back. Meet One of the Artists Who Created It,” Slate, July 13, 2016, bit.ly/4j6oq78.

“Jorge Socarrás,” Discogs, bit.ly/42pg7N1.

Manhattan Phone and Address Directories, 1984-1988, The New York Public Library.

Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 319-323.

“Silence=Death,” David Zwirner, bit.ly/4ceu2tz.

Theodore Kerr, “How Six NYC Activists Changed History With ‘Silence = Death,’” Village Voice, June 20, 2017, bit.ly/4hQv8wR.

Thessaly La Force, Zoë Lescaze, Nancy Hass, and M.H. Miller, “The 25 Most Influential Works of American Protest Art Since World War II,” The New York Times, October 15, 2020, bit.ly/4l0N2Qj.

W. Jake Newsome, Pink Triangle Legacies: Coming Out in the Shadow of the Holocaust (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2022). [source of Howard pull quote, 122]

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?