Rose Schneiderman Residence

overview

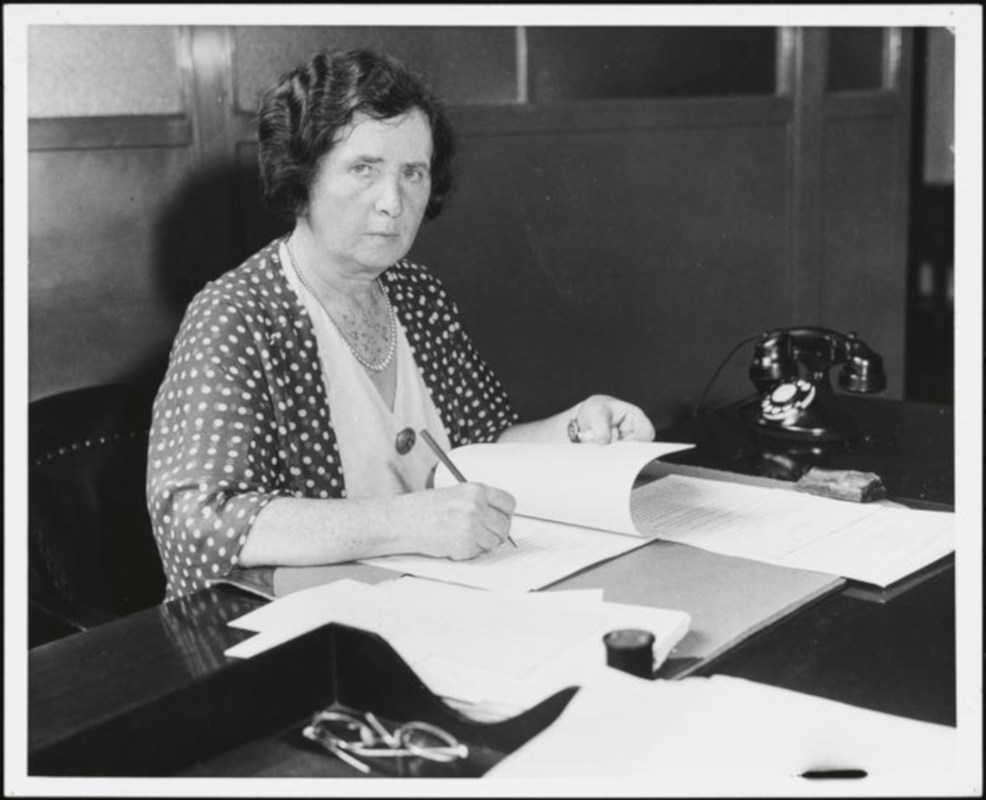

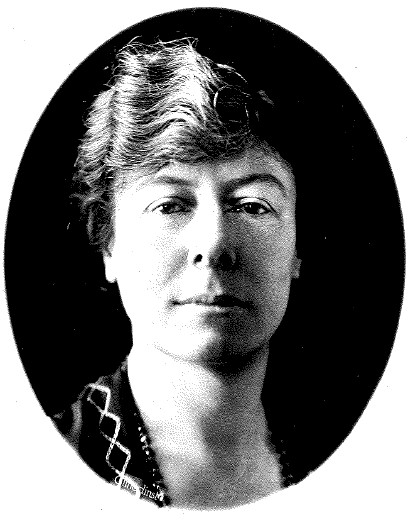

Rose Schneiderman, who lived in this Bronx building from 1925 to 1937, was a working-class immigrant who became one of the most significant labor reformers of the early 20th century.

She was the president of the Women’s Trade Union League, an important organization for women who thrived in the homosocial world of labor reform, and also served at the local, state, and federal levels, including as an advisor to Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, to help improve the lives of working-class women.

History

Rose Schneiderman (1882-1972) was born into a Jewish family in Poland (then part of Russia) and immigrated to the United States as a girl. After limited schooling she went to work, first in a department store and then in a garment factory sewing linings into men’s caps. She and a co-worker organized the factory workers into a union and she became a leader when the capmakers undertook a successful strike in 1905. Her abilities led to an invitation from the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) to join their efforts at union organizing.

The WTUL was a national organization founded in 1903 as a cross-class alliance of working women and more affluent allies focused on improving labor conditions for women. The WTUL created a homosocial world where activist women could advocate for a more just society. Among the other activists with whom Schneiderman worked at the WTUL were Mary Dreier, Helen Marot, Frieda Miller, Pauline Newman (Schneiderman’s closest friend), and Maud O’Farrell Swartz. Schneiderman became vice president of the New York WTUL in 1906 and two years later left her factory job to become a full-time union organizer.

Schneiderman’s and the WTUL’s organizing resulted in the 1909 strike known as the “Uprising of the 20,000,” when shirtwaist workers, mostly teenage girls, walked off the job. This was an extraordinary strike since organizing women workers was difficult, in part because most young women assumed they would only be working until they married and because the male-dominated unions were not welcoming to women workers.

The fire at the Triangle Waist Company in March 1911 that killed 146 workers, most of whom were women, strengthened Schneiderman’s commitment to labor reform. She had worked to organize the women in this large factory and knew some of the victims. At a memorial held at the Metropolitan Opera House (demolished), Schneiderman demonstrated her abilities as an impassioned orator:

“I would be a traitor to those poor burned bodies if I were to come here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public – and we have found you wanting. The old Inquisition had its rack …. The rack is here in the firetrap structures that will destroy us the minute they catch fire …. I can’t talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. And the only way is through a strong working-class movement.”

In 1912, while speaking in Cleveland, Ohio, Schneiderman declared that “the worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.” Although Schneiderman did not originate the bread and roses link with labor, the term became associated with her. Her point was that women workers wanted a living wage, health care, and decent housing (the bread), but also limited hours and time for educational and cultural pursuits (the roses).

The inability of women to become union leaders resulted in Schneiderman and many of the other women associated with the WTUL to turn to suffrage as a route for women to gain power. It was at a suffrage rally in 1912 that Schneiderman met Maud O’Farrell Swartz, an Irish-born printer who soon became active in the WTUL and became Schneiderman’s life partner, although they never lived together. Schneiderman lived with her mother and siblings at 59 Second Avenue in Manhattan in 1910, before they moved to the Bronx, first to 859 Macy Place and then, in 1925, to the new apartment building at 1940 Andrews Avenue. Following her mother’s death in 1937 (and Swartz’s death at about the same time), Schneiderman moved to an apartment on the 14th floor of 235 East 22nd Street in Manhattan.

In 1918, Schneiderman was elected president of the New York WTUL and, in 1926, became president of the national organization as well. In the 1920s, Schneiderman became a strong advocate for a minimum wage law for women, focusing particularly on the plight of exploited African American laundry workers. Working with fellow reformer Molly Dewson, they persuaded the New York State Legislature to pass such a bill in 1933.

In 1919, Schneiderman and Swartz met Eleanor Roosevelt at the First International Congress of Working Women. Roosevelt became active in the WTUL and Schneiderman and Swartz became close confidants of Eleanor and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, visiting with Eleanor at her Val-Kill house and both Franklin and Eleanor at their Hyde Park estate. Frances Perkins, a close friend and colleague of Schneiderman and Swartz said:

These intelligent trade unionists made a great many things clear to Franklin Roosevelt that he could hardly have known any other way.

President Roosevelt appointed Schneiderman as the only woman on his National Recovery Administration’s Advisory Board. Later, her advice was crucial to the development of the National Labor Relations Act, the Social Security Act, and the Fair Labor Standards Act. She served as New York State’s Secretary of Labor from 1937 to 1943. Schneiderman remained active in reform efforts until the WTUL closed down in 1955, at which time she retired. A New York Times editorial following her death proclaimed that Schneiderman “did more to upgrade the dignity and living standard of working women than any other American.”

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (September 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown

- Year Built: 1924-25

Sources

Annelise Orleck, Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

John Thomas McGuire, “From Socialism to Social Justice Feminism: Rose Schneiderman and the Quest for Urban Equity, 1911-1937,” Journal of Urban History 35 (November 2009), 998-1019.

Kathleen Banks Nutter, “Rose Schneiderman,” American National Biography, 1999.

“Mass Meeting Calls for New Fire Laws,” The New York Times, April 3, 1911, 3.

Minerva Brooks, “Rose Schneiderman in Ohio,” Life and Labor 2 (September 1912), 288.

Nancy Schrom Dye, As Equals & As Sisters: Feminism, Unionism, and the Women’s Trade Union League of New York (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1980).

“Rose Schneiderman,” editorial, The New York Times, August 14, 1972.

“Rose Schneiderman Dies; Pioneer Women’s Union Leader,” The New York Times, August 2, 1972.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?