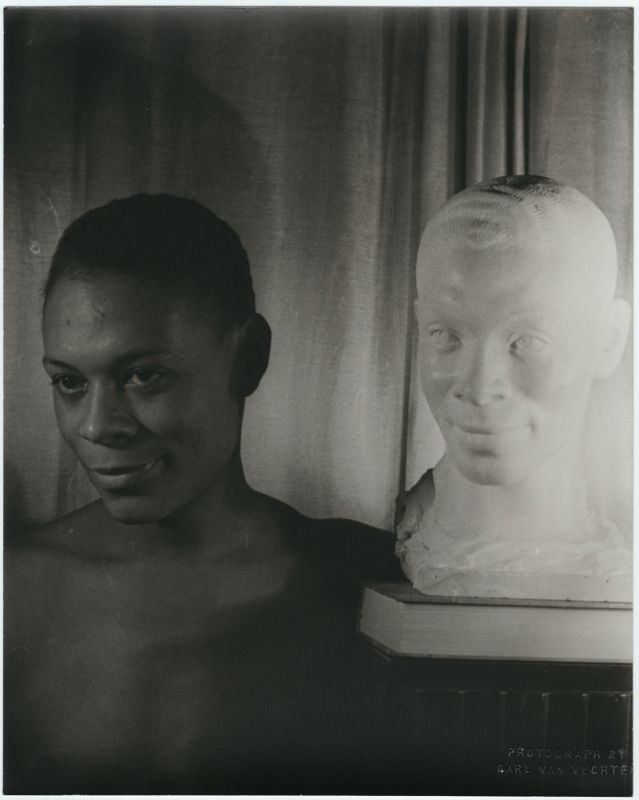

Richmond Barthé & “Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho”

overview

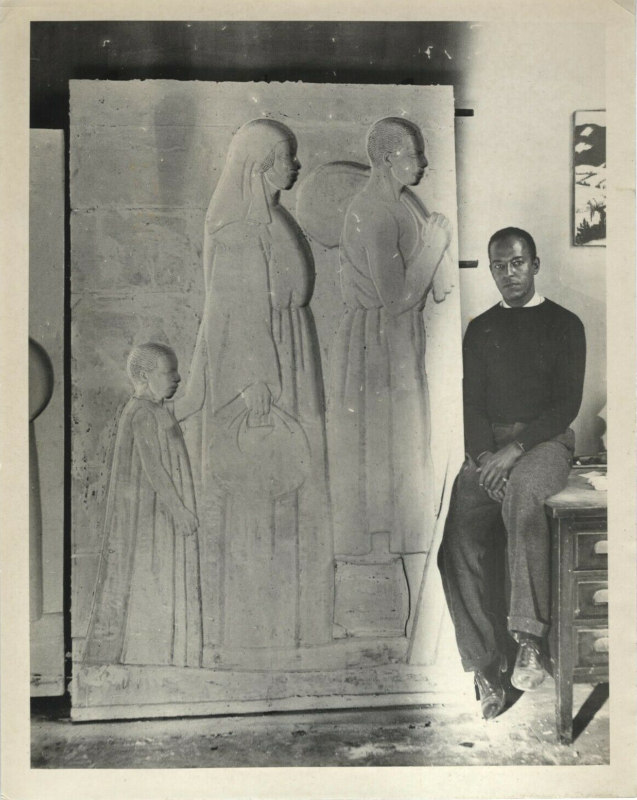

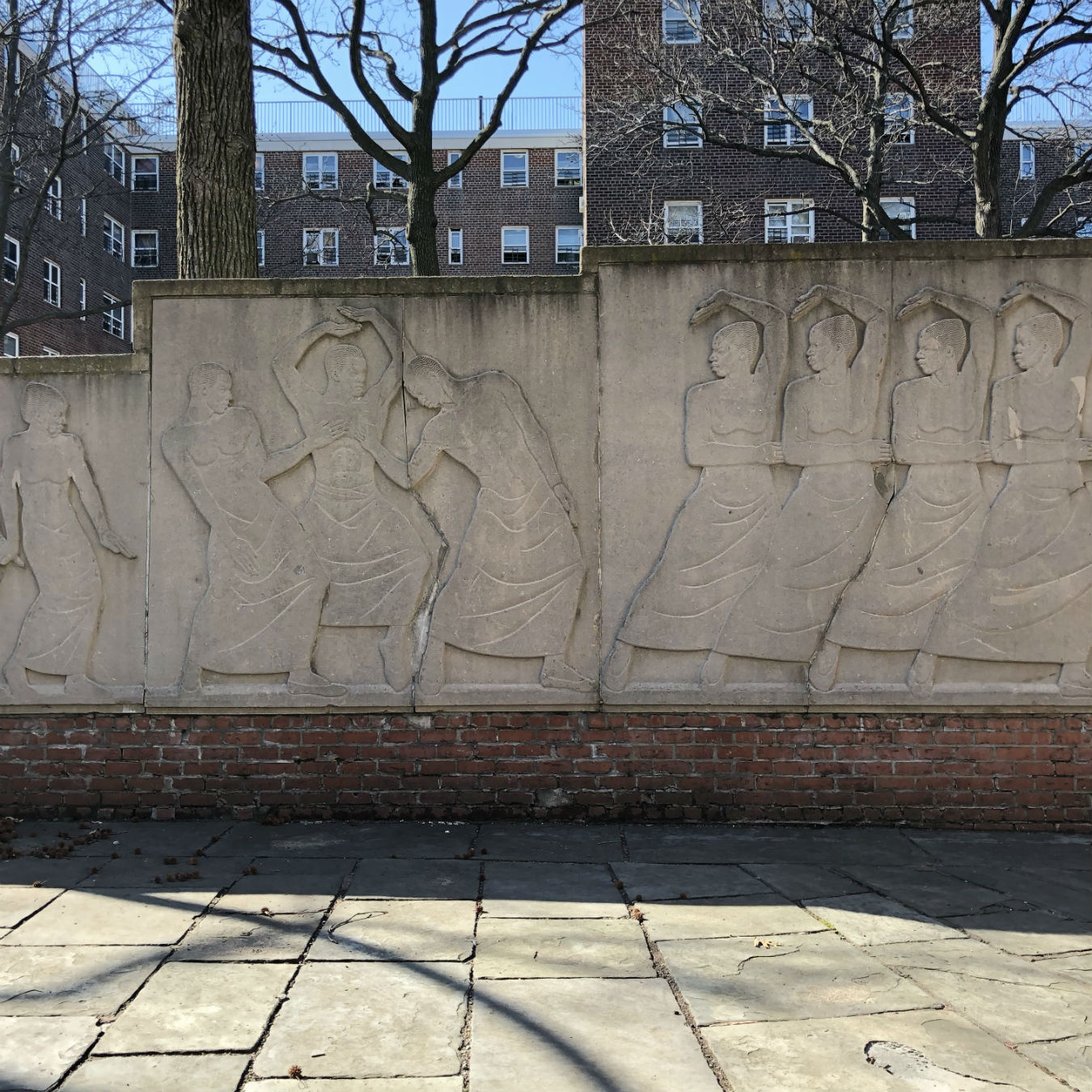

Sculptor Richmond Barthé created this 8-foot by 80-foot frieze Exodus and Dance (completed in 1939) for the Harlem River Houses, which was later named Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho and installed at the Kingsborough Houses in 1941.

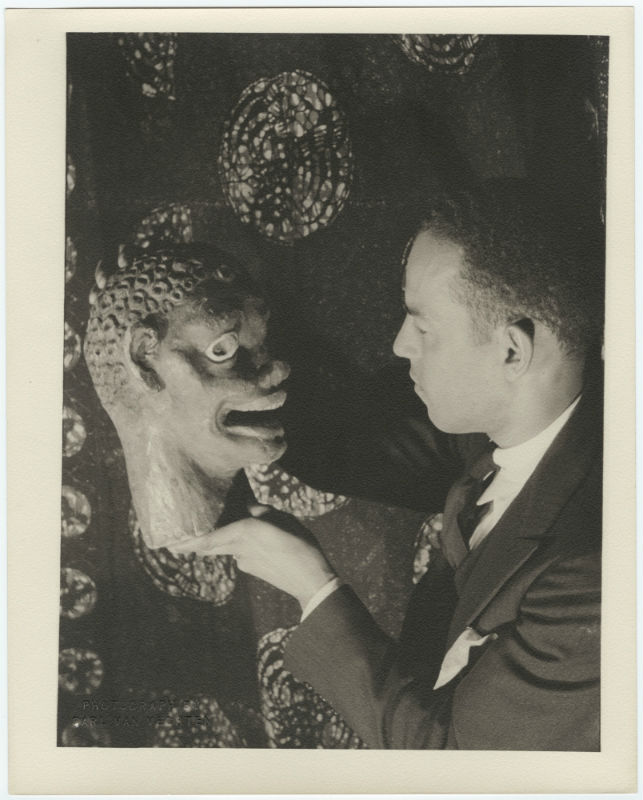

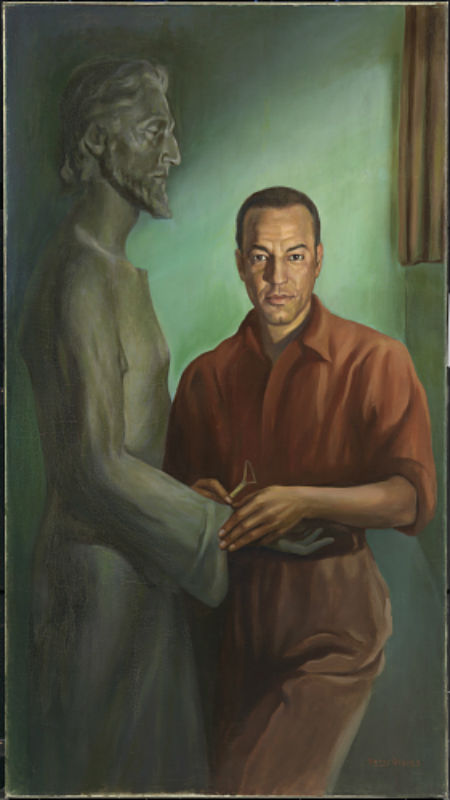

Recognized as the most important 20th-century African-American sculptor, Barthé is known for his portrayals of figures from Black history, notable stage and dance performers, religious subjects, and public works.

History

Richmond Barthé (1901-1989), born and raised in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1924 to 1928, where he was introduced to sculpture in his senior year. In 1929, he visited Harlem to join its artistic and cultural scene now known as the Harlem Renaissance, entering established networks of gay social circles. Although he never publicly revealed his homosexuality, Barthé’s sculptures often displayed homoerotic themes that exploited the Black male nude for its political, racial, aesthetic, and erotic significance.

In 1931, Barthé moved his studio to 236 West 14th Street (façade since altered) to be closer to his racially and economically diverse customers and friends. Among his most important supporters were lifelong friends, philosopher Alain Locke and writer Richard Bruce Nugent, who was also his one-time lover. Barthé also socialized with the era’s luminaries, such as writers Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, and Countee Cullen, arts patron Harold Jackman, photographer Carl Van Vechten, writer Lincoln Kirstein, and artists Paul Cadmus and Jared French.

Barthe’s largest work, and his first in relief, was the cast-stone frieze Exodus and Dance (completed 1939), which was originally intended for the Harlem River Houses (1936-37), one of the nation’s first federal public housing projects specifically built for African Americans. He was hired, through the Works Progress Administration, as part of a team of sculptors commissioned to create public art for that project. Barthé designed a site-specific work for the back wall of an amphitheater that he envisioned would be used for music, dance, and theater performances. Barthé created scenes using his best-known subject matter: Biblical imagery and African dance. The left side of the frieze was inspired by Marc Connelly’s 1930 Pulitzer-Prize winning play The Green Pastures, which portrays episodes from the Old Testament through the eyes of an African-American child. The right side, where the influence of Art Deco design is fully realized, African dancers inspired by David Wendell Guion’s 1929 ballet Shingandi come to life.

All my life I have been interested in trying to capture the spiritual quality I see and feel in people, and I feel that the human figure as God made it, is the best means of expressing this spirit in man.

Months after the Harlem River Houses opened, Barthé’s panels were still in storage since the amphitheater project was never built. As a federal employee, he had no control over what was done with his work and in 1941 the panels were installed without his consultation on one of the main walks at the Kingsborough Houses. The work was renamed Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho. Barthé was disappointed since, although low-income federal housing, African Americans were not the primary residents and therefore he felt the inspirational power of his work was diminished. Today, the largely African-American residents fondly refer to the work as “The Wall.”

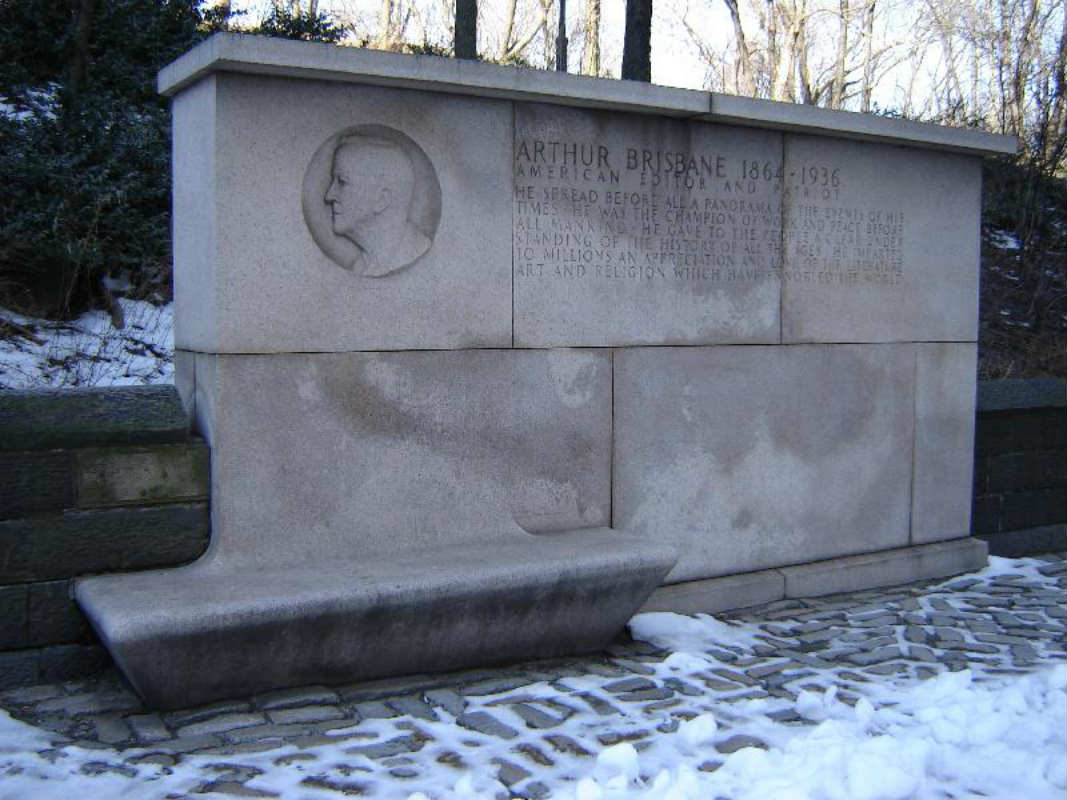

Barthé’s other public works in New York City include the bas-relief effigy on the Arthur Brisbane Monument, located at Central Park’s Fifth Avenue perimeter wall (at East 101st Street), and the busts of George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington at the Hall of Great Americans, located on the grounds of Bronx Community College. He had numerous celebrities and notables as clients and his portrait busts include Katharine Cornell as Juliet (1942), featuring the actress Katharine Cornell and his friend, cabaret performer Jimmie Daniels. Today, Barthé is represented in the permanent collections of numerous major museums.

In 1947, he moved to Jamaica in the West Indies where he remained until the mid-1960s and then afterwards lived in Europe. Barthé returned to the US in 1977 and settled in Pasadena, CA. He soon developed a friendship with the actor James Garner who became Barthé’s benefactor and advocate, helping him copyright his works.

Entry by Ken Lustbader, project director (February 2018).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Sources

Asantewa Boakyewa, Richmond Barthé’s “Green Pastures,” Newsletter of the Center for Africana Studies at Johns Hopkins University, Fall 2008, 5.

George E. Haggerty, ed., Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 2000).

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Gene Andrew Jarrett, eds., The New Negro: Readings on Race, Representation, and African American Culture, 1892-1938 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

James Smalls, “Barthé, James Richmond (1901-1989),” GLBTQ Encyclopedia, 2015 (accessed February 18, 2018), bit.ly/2BFTFo3.

Marci Reaven and Steve Zeitlin, Hidden New York: A Guide to Places That Matter (New Brunswick: Rivergate Books, 2006).

Margaret Rose Vendryes, Barthé: A Life in Sculpture (Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2008).

Margaret Rose Vendryes, e-mail to Ken Lustbader/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, February 7, 2021.

Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson, A History of African American Artists: From 1792 to the Present (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993).

Steven Otfinoski, African Americans in the Visual Arts (New York: Facts on File, 2003). [source of pull quote]

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?