Picket at the Great Hall, Cooper Union, Second-Ever U.S. Gay Rights Protest

overview

On December 2, 1964, the second-ever public demonstration for gay rights in the United States – and the first to challenge the psychiatric profession – took place outside the Great Hall at Cooper Union.

Organized by Randy Wicker, three gay men and a lesbian handed out homophile literature and protested against a psychiatrist who was there to present a lecture entitled “Homosexuality, A Disease.”

History

A picket at entrances to the Great Hall at Cooper Union on December 2, 1964, was later identified as the second public demonstration for gay rights in the United States by Barbara Gittings, co-founder of the Daughters of Bilitis, New York Chapter, in 1958. This was also the earliest known public challenge by the LGBT community against the psychiatric profession. The Cooper Union event followed the September 19, 1964, picket in front of the U.S. Army Building in Lower Manhattan, which protested the military’s treatment of gay people. Both pickets were organized by Randy Wicker.

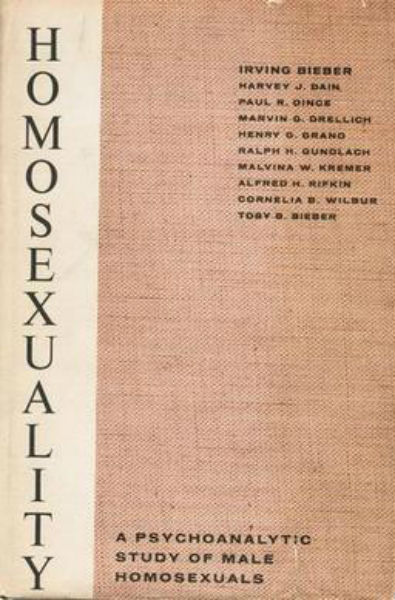

Dr. Paul R. Dince, Associate in Psychiatry at New York Medical College, was invited as part of the Cooper Union Forum Series to give a lecture titled “Homosexuality, A Disease.” Though this was to be his first public lecture, Dince had been a contributor to Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals, a book published in 1962 about the development of male homosexuality by the New York psychoanalyst Irving Bieber. The result of a 10-year investigation, the work made Bieber an influential “expert,” or notorious homophobe, depending on one’s perspective at the time. The book received a largely negative response from the gay community, with reviews in The Ladder, Mattachine Review, and New York Mattachine Newsletter.

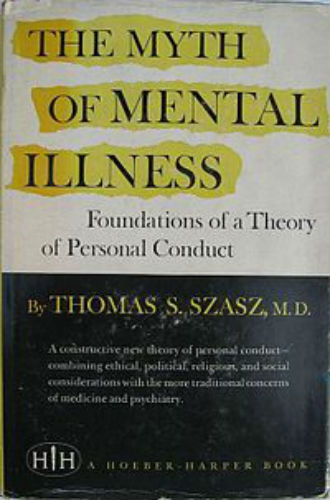

The prevailing psychiatric viewpoint that homosexuality was a disease was already under attack. In 1961, Thomas S. Szasz wrote a book, The Myth of Mental Illness, which took on the “mental health” profession, citing psychiatrists as making prejudiced moral judgments under a pseudo-scientific aura. His critiques proved valuable as tools for the homophile movement. In New York, Wicker, incensed by a radio program that had psychiatrists discussing homosexuality as a disease, convinced WBAI radio to allow a group of gay men to discuss their lives on the “Live and Let Live” program in 1962. This is believed to have been the first such radio program.

As early as October 1963, Frank Kameny, an influential early gay rights strategist and leader of the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., had attempted to convince his board to adopt a statement that homosexuality was not a disease. (He finally succeeded in March 1965 with the quite radical for its time tenet: “Homosexuality is not a sickness, disturbance, or other pathology in any sense, but is merely a preference, orientation, or propensity, on a par with, and not different in kind from, heterosexuality.”)

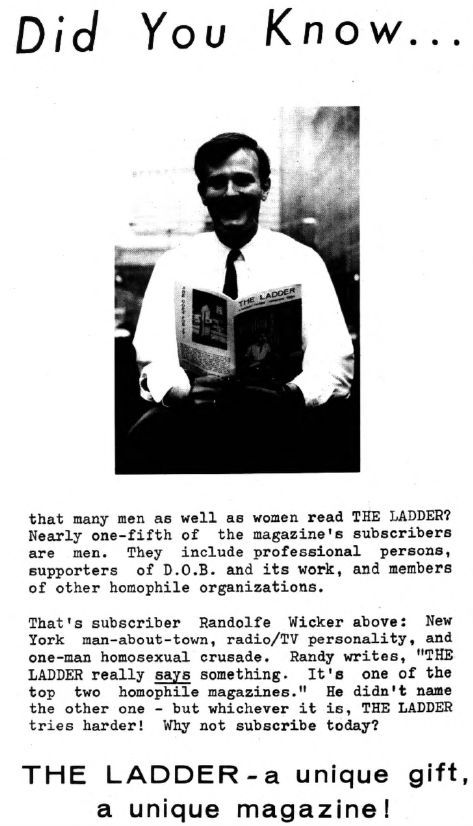

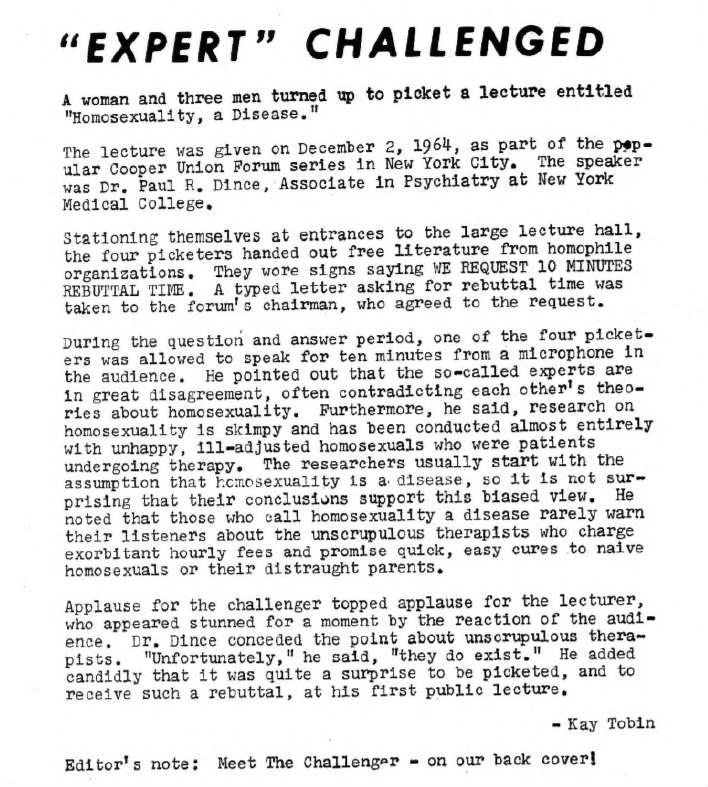

At the Cooper Union, Wicker, two other gay men (one was probably Craig Rodwell), and a lesbian, Kay Tobin (real name Kay Lahusen), stationed themselves at the entrances to the Great Hall, wearing signs “WE REQUEST 10 MINUTES REBUTTAL TIME,” and handed out homophile literature. The forum chairman, apparently wanting a lively discussion, agreed to the group’s request. After Dr. Dince’s talk, Wicker spoke from a microphone in the audience, challenging the disease theory of homosexuality. He received more applause than Dince, who expressed surprise at the picket of, and challenge to, his speech, as well as the audience reaction. Tobin wrote an article on the event for the Daughters of Bilitis’ publication The Ladder, and Wicker appeared on the issue’s back cover.

The Cooper Union demonstration was the first of several campaigns over the next ten years that LGBT activists organized to challenge the psychiatric profession’s stance on homosexuality, which played a large part in shaping homophobia in wider society for decades. In April 1974, American Psychiatric Association (APA) members voted to remove homosexuality from its list of mental disorders, following a similar vote by its board of trustees in December 1973.

Entry by Jay Shockley, project director (July 2018; last revised April 2024).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Frederick A. Petersen

- Year Built: 1851-59

Sources

The Earliest Gay Pickets: When, Where, Why,” list prepared in 2005 by Barbara Gittings, in Tracy Baim, Barbara Gittings: Gay Pioneer (Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions, 2015).

Kay Tobin, “‘Expert’ Challenged,” The Ladder, February/March 1965, p.18.

Lillian Faderman, The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), pp. 283-284.

Michael G. Long, editor, Gay Is Good: The Life and Letters of Gay Rights Pioneer Franklin Kameny (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014).

Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals,” Wikipedia, bit.ly/2mozVMQ.

Randy Wicker, interview with NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, June 28, 2018.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?