Pauline Newman & Frieda Miller Residence

overview

Pauline Newman and Frieda Miller, partners of over 50 years who lived in this building in the 1920s, were major players in the world of labor reform and union organizing at both the city, state, and national levels.

They are an example of the cross-class and cross-ethnic alliances that were generated in the labor reform movement, especially at the Women’s Trade Union League.

History

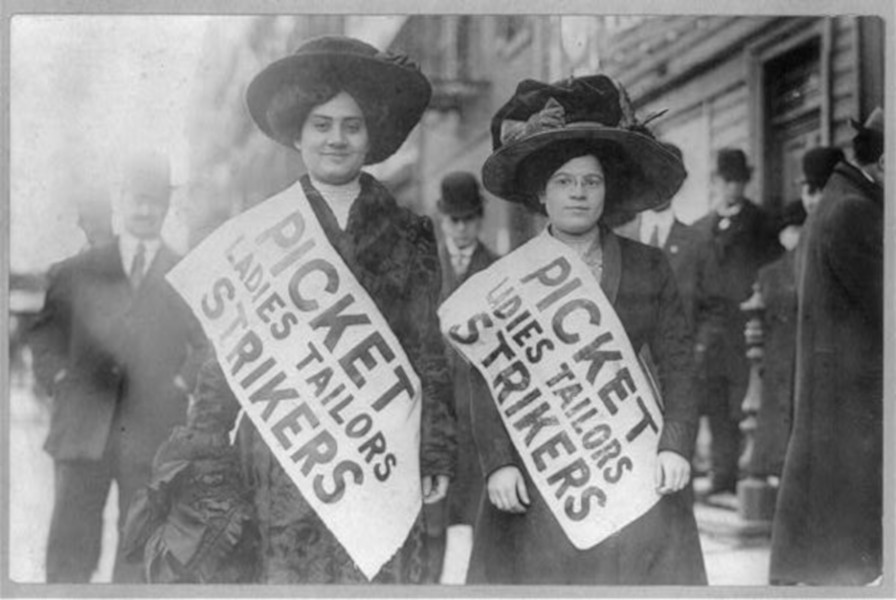

Pauline M. Newman (c. 1893-1986) immigrated to New York from Lithuania with her family in 1901. In 1904, when she was only 11, Newman went to work in a hairbrush factory and the next year was hired by the Triangle Waist Company to cut loose threads from shirtwaists, learning to hide, since she was underage, when inspectors came to the factory. She taught herself English and through her reading became a firm supporter of socialism, joining the Socialist Party in her teens (she ran for Congress on the Socialist ticket in 1915). Historian Annelise Orleck refers to Newman as “a die-hard union loyalist.” Newman joined the shirtwaist strike of 1909, known as the “Uprising of the 20,000,” and became a fiery speaker in both English and Yiddish (she carried her own soapbox when she campaigned for union organizing and in support of strikes throughout the country).

Newman’s prominence as a speaker during the shirtwaist strike led directly to her employment as the first woman organizer hired by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). She worked for the ILGWU for much of the rest of her life. She was the founder and then director of the ILGWU’s Union Health Center for over 60 years. She also worked as an inspector for the Joint Board of Sanitary Control, an organization established jointly by the union in the woman’s cloak industry and the factory owners, lectured extensively, and became a fervent advocate for suffrage. Newman was also active with the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), an advocacy group of wealthy and working-class women, led from the 1920s through the 1950s by her closest friend, Rose Schneiderman.

The 1911 Triangle fire that killed 146 shirtwaist workers, most of whom were women, had a profound impact on Newman, who had worked at the factory and knew many of the girls who had died in the blaze. She frequently noted that the job organizing for the ILGWU saved her life. Newman served as a factory inspector for the Factory Investigating Commission (FIC) that was established by New York State in the wake of the Triangle disaster, working with WTUL activist Mary Dreier, who was a member of the FIC, Frances Perkins, who was also an inspector, and with Schneiderman. These women became close friends and confidants. Orleck describes the impact of their friendship:

Through their friends, Schneiderman and Newman got the chance to participate in the building of the U.S. welfare state – a remarkable opportunity for two self-educated immigrant former shop girls.

Newman met Frieda S. Miller (1890-1973), the daughter of an affluent lawyer from Wisconsin, in 1917. Miller was working as a research assistant and lecturer in the economics department at Bryn Mawr College when she met Newman, who had established a branch of the WTUL in Philadelphia. Miller left Bryn Mawr to assist Newman, becoming secretary of the Philadelphia WTUL, and they were soon living together, a relationship that lasted for over 50 years.

In 1923, Miller and Newman attended the International Congress of Working Women in Vienna as U.S delegates. They then moved to New York, eventually settling, along with Miller’s daughter, into an apartment on the 14th floor of the new apartment building at 299 West 12th Street. Miller, like Newman before her, worked as an inspector for the Joint Board of Sanitary Control, and then went on to work as a researcher for the New York City Committee of State Charities Aid and for the Welfare Council.

From 1929 until 1938, Miller was the director of the New York State Department of Labor’s Division of Women in Industry where she was responsible for guiding the passage of a women’s minimum wage bill, a project that was forcefully advocated by her WTUL colleagues Rose Schneiderman and Molly Dewson; Newman was appointed to the state commission that reviewed the need for this law. In 1938, she was appointed as New York State’s Commissioner of Labor and, in 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt made her director of the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor. Unlike Newman, but like their friend and colleague Frances Perkins, Miller was able to gain power at state and federal levels, largely because of her middle-class background. Annelise Orleck examines this issue:

Pauline Newman, one of the most widely read and intellectually creative members of the [WTUL] network, was always limited to an advisory role. There are many reasons for this, but Newman’s blunt aggressiveness and fondness for masculine dress may have had something to do with it.

Both Newman and Miller dedicated their entire working lives to the improvement of conditions for workers, especially for women workers, focusing on both economic and social issues that would improve the lives of the working class.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (September 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Emery Roth

- Year Built: 1929-31

Sources

Annelise Orleck, Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

Francesco L. Nepa, “Frieda Segelke Miller,” National American Biography, 1999.

Marilyn Elizabeth Perry, “Pauline Newman,” National American Biography, 1999.

Nancy Schrom Dye, As Equals & As Sisters: Feminism, Unionism, and the Women’s Trade Union League of New York (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1980).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?