Paul Thek Residence & Studio

overview

Paul Thek, who lived and worked at 254 East 3rd Street in at least the late 1960s, was a visual artist and one of the first to create installation art.

He became known in America in the 1960s for making realistic sculptures of meat and dismembered body parts, but by the end of his career his work had been largely eclipsed by other artists.

History

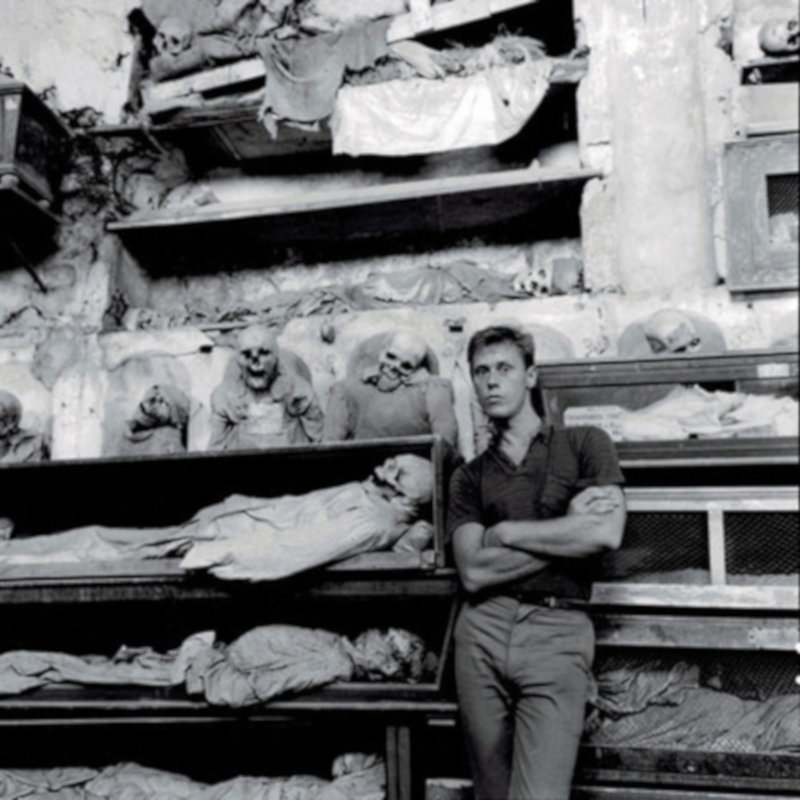

Paul Thek (1933-1988) was born in Brooklyn and studied painting at Cooper Union, starting in 1951. In the oppressively homophobic atmosphere of the 1950s, Thek managed to live a relatively open gay life with a circle of friends whom he met while studying. Set designer Peter Harvey and painter Joseph Raffael were among his circle and the three of them travelled, dated, and created together in a communal atmosphere. Thek met photographer Peter Hujar on a trip to Florida in 1957 and the two became lovers for several years. In 1963, Thek and Hujar journeyed to Sicily where they visited the catacombs of Palermo. This trip was an inspiration and Thek focused his art for the rest of his career on the themes of death, ephemerality, and time. He said of this experience, “It delighted me that bodies could be used to decorate a room, like flowers,” and one can see the impact of this in his most famous works of art.

Back in New York, Thek began making his “meat pieces” in 1965, his first commercially successful works of art. Realistic sculptures made of beeswax were painstakingly crafted by Thek to look like slabs of meat or disembodied body parts. Thek hated the then en vogue art movement of Minimalism; his “meat pieces” (collectively known as “Technological Reliquaries”) attacked the cold, clean lines of that movement and also lambasted the deadpan world of Pop Art. Thek placed the sculptures in pristine Plexiglass boxes, but reserved one to be placed inside one of Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box sculptures made one year prior in 1964, contrasting the banality of Warhol with Thek’s visceral, emotive sculpture. This work was celebrated at the time for bravely defying the dominant artistic movements holding sway over New York’s art world, and turned Thek into an iconoclastic cult figure.

At his apartment, which he also used as his studio, in 1967, Thek began work on The Tomb, which would become his most famous artwork. For this piece, Thek made a realistic cast of his own body, dressed it in a pink suit and laid it to rest in a pink ziggurat pyramid. Littered around the body were paraphernalia related to drug use, and on the figure’s face were laid psychedelically painted discs. The Whitney Museum of American Art exhibited the piece in a group show in 1968 and erroneously subtitled it “Death of a Hippie,” which led people to interpret it as the death of hippie culture and a response to the Vietnam War. Protestors of the war laid flowers next to The Tomb using Thek’s effigy as an ersatz fallen comrade. Critics hailed Thek’s work as a masterpiece of American sculpture, and requests came in from galleries across the country to recreate the installation. Thek eventually grew annoyed at the sculpture’s notoriety and it is now assumed to have been destroyed.

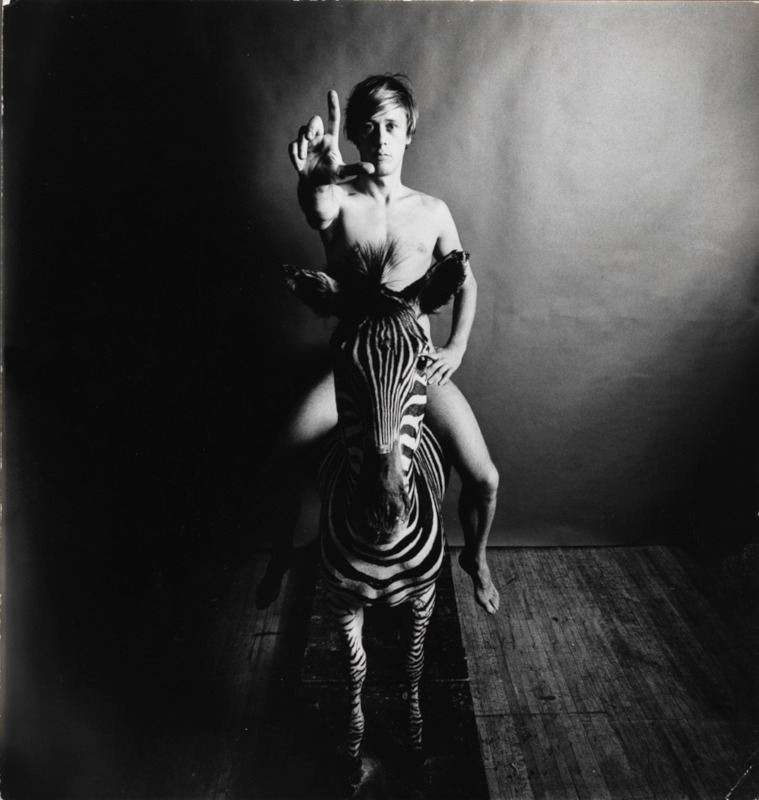

Thek left America at the height of his fame in 1967 to live in Europe. While there he became known for installation work, creating “environments” out of junk material that were designed to be ephemeral. He came back to New York in 1976 to discover he had been largely forgotten. He grew angry at the art world and struggled to regain its attention. He worked in supermarkets and as a janitor in hospitals to get by, exhibiting infrequently and without acclaim. He died in New York in 1988 of an AIDS-related illness at the age of 54. Despite famous friends, such as Susan Sontag and Robert Wilson, who gave eulogies at his funeral at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, his death passed without much comment. Since his death, The Whitney exhibited an extensive retrospective in 2010 intended to “introduce” Thek to a broader American audience, and in 2013 the Leslie Lohman Museum exhibited Thek’s work from the 1950s, which it argues was “the gayest of his entire career.”

Entry by George Benson, project consultant (April 2021).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Schneider & Herter

- Year Built: 1898

Sources

“Paul Thek: Diver, A Retrospective,” The Whitney Museum of American Art, bit.ly/3rtJcCV.

Holland Cotter, “Believing Is Seeing (Or, the Meat Of the Matter),” The New York Times, October 21, 2010, nyti.ms/3qtRTMc.

Sharmila Venkatasubban, “Reclaiming Paul Thek,” Carnegie Magazine, Spring 2011, bit.ly/3ehKcGJ.

“The Man Who Couldn’t Get Up,” Frieze, August 9, 1995, bit.ly/3bx3OoF.

John Perreault, “Paul Thek Revised: The Missing Years,” Arts Journal, November 15, 2010, bit.ly/3t0OE0x.

Maika Pollack, “Paul Thek and His Circle in the 1950s’ at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art,” Observer, June 18, 2013, bit.ly/3rG9LF2.

Julian Elias Bronner, “Paul Thek and His Circle in the 1950s,” Art Forum, bit.ly/2OhcbLU.

Emily Colucci, “Gay Pride and Self-Representation Under the Lavender Scare,” Hyperallergic, April 24, 2013, bit.ly/3kVBwaa.

Jonathan David Katz and Peter Harvey, “Paul Thek and His Circle in the 1950s,” Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, bit.ly/3v4DhXi.

“Paul Thek,” Wikipedia, (accessed March 8, 2021) bit.ly/38hptPx.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?