Paul Taylor Residence

overview

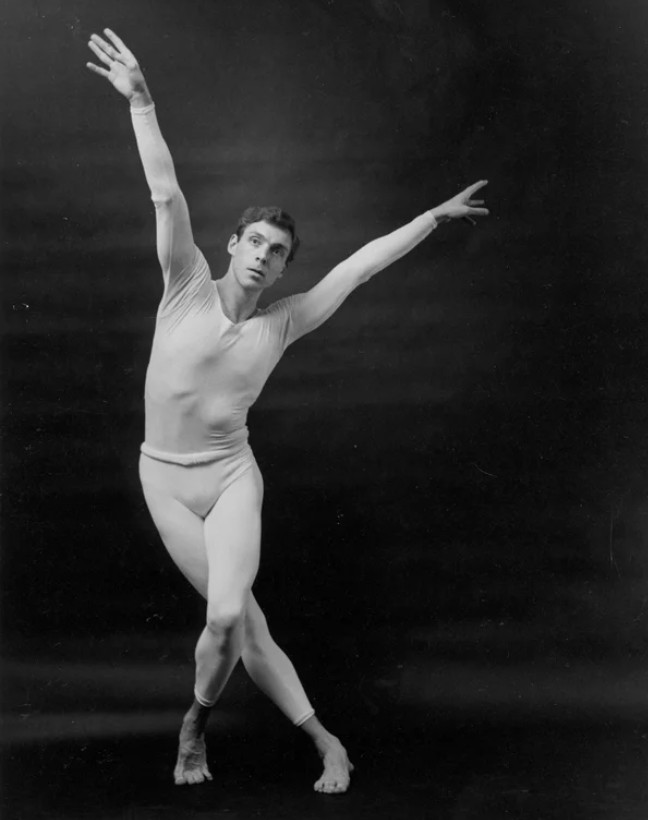

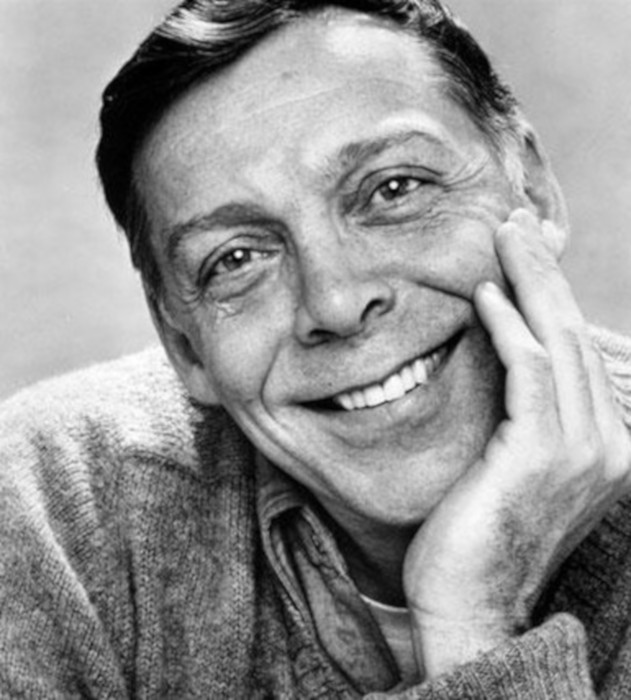

Paul Taylor, one of the creative geniuses of Modern dance, lived at 27 Vandam Street from c. 1970 until 2009, during which he mesmerized the public as a dancer and then as one of the most innovative and best loved Modern dance choreographers.

History

From c. 1970 until 2009, this small Federal style brick house was the home of Paul Taylor (1930-2018), dancer and pioneering American Modern dance choreographer whose Paul Taylor Dance Company was among the most popular in the world. (When he sold the house, the funds went to his dance company.)

Taylor discovered dance while at Syracuse University where he was studying art and was a member of the swim team. Taylor left Syracuse before his senior year and enrolled in dance classes at the American Dance Festival at the University of Connecticut, the Juilliard School, and at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. He studied with or danced for many of the most avant-garde dancers and choreographers of the day, including Merce Cunningham, Doris Humphrey, Pearl Lang, José Limon, Martha Graham, Jerome Robbins, Antony Tudor, and Charles Weidman.

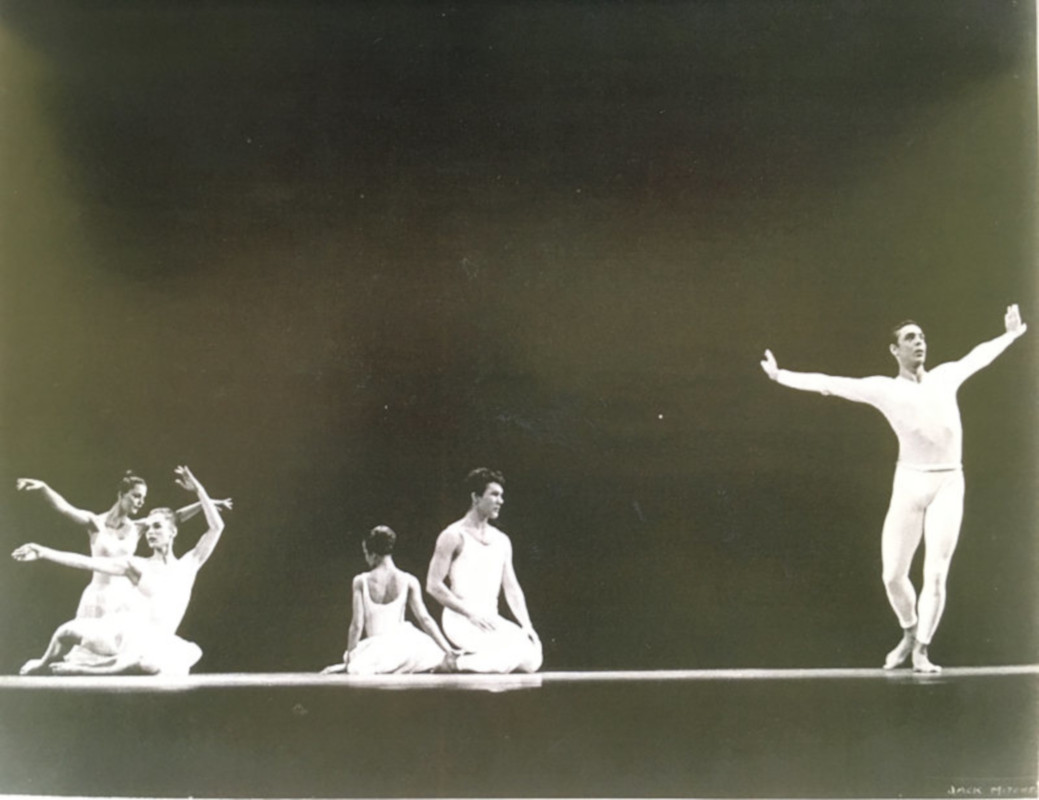

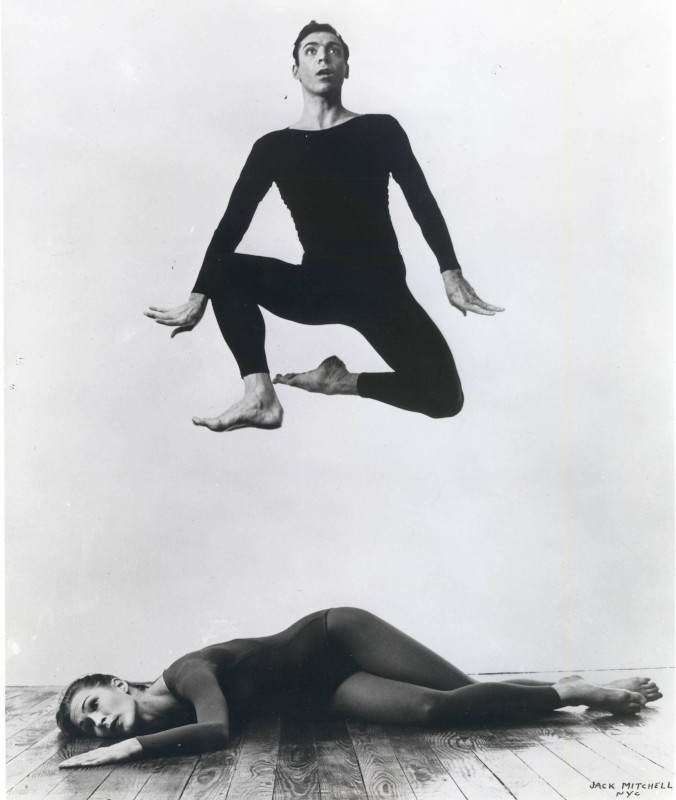

In 1954, Taylor met Robert Rauschenberg, and fell into a crowd of progressive artists that included Rauschenberg’s then-partner Jasper Johns, composer John Cage, and artist Ellsworth Kelly, all of whom would collaborate with Taylor on his dance works. Beginning in 1955, the tall, athletically-built Taylor danced for Martha Graham. He also started choreographing on the side, creating experimental pieces such as Duet (1957), a 4½-minute work set to Cage’s music, with costumes by Rauschenberg, where he stood next to a woman seated on the floor and neither moved.

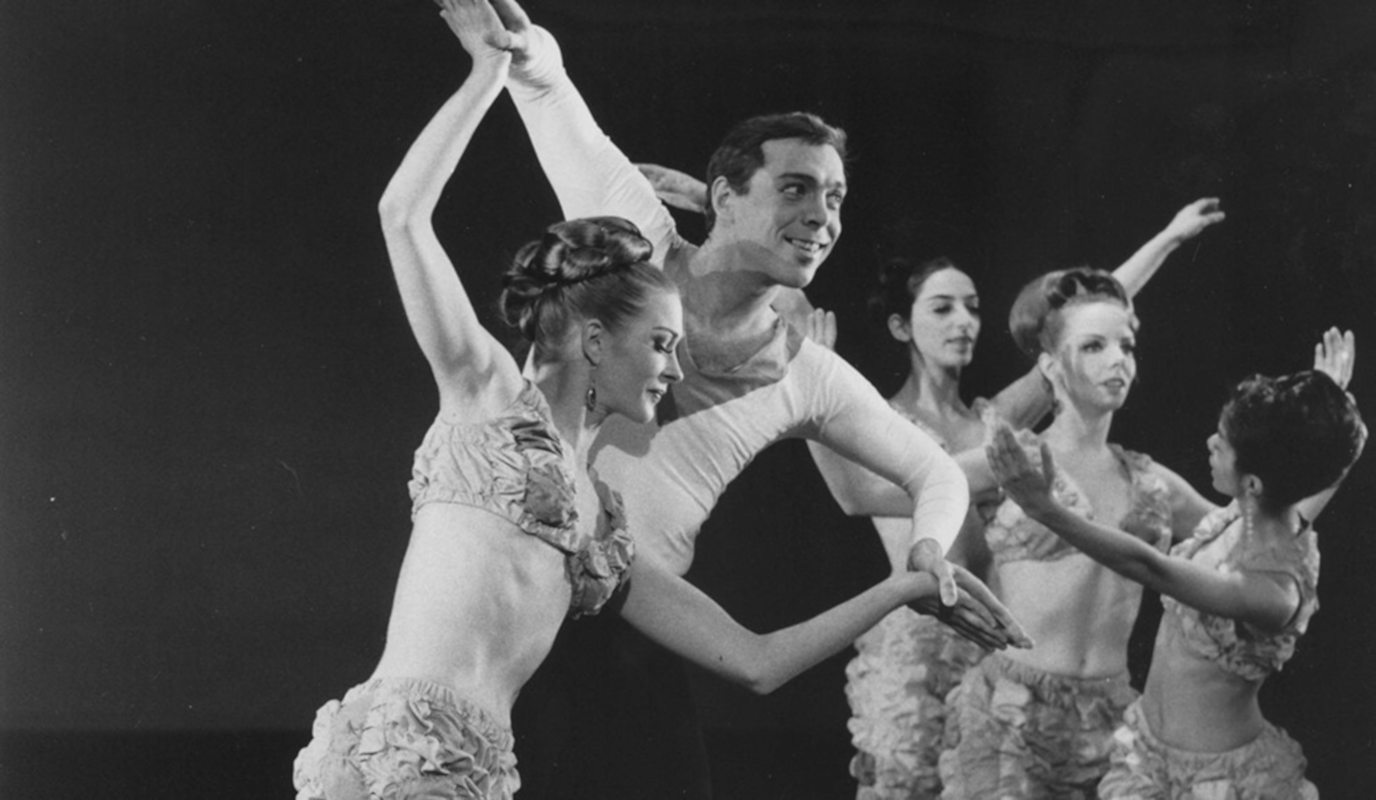

In 1958, Taylor established his own company, the Paul Taylor Dance Company. Over the next six decades he created scores of new works (he is credited with 147 pieces). Taylor danced in many of his works, until retiring from the stage in 1974. A major transformation in his style came in 1962 with the premiere of Aureole, a lyrical piece set to music by Handel which was widely popular (this piece caused a rupture in his relationship with Rauschenberg and many of his other avant-garde colleagues). In 1968, it was staged by the Royal Danish Ballet (a recording of the Danish Ballet dancing Aureole, with Rudolf Nureyev dancing the role Taylor originated, is linked below), the first of many Taylor works mounted by ballet companies around the world. Taylor’s style, quite different from traditional ballet style, is one of bodies anchored to the ground, and he reveled in creating dance from every day “found” movements (much as Rauschenberg and Johns used everyday objects in their art). Nowhere was this more evident than in his masterpiece Esplanade (1975), where there are no traditional dance steps, but the dancers walk, run, skip, fall, rise, slide, roll, and jump in joyous, sad, and tender movements to Bach violin concertos. Taylor’s output was extremely varied, ranging from lyrical, to funny, to dark works that explored the depravity of human beings, such as Last Look (1985). As he said:

I categorize my dances as pretty ones and ugly ones … then there’s an in-between category … works that are just funny.

He could also choreograph moving works, most evident in Promethean Fire (2002), his response to 9/11.

Taylor kept his personal life private. In the mid-1950s, he met George Wilson, a deaf man who lived with him (Taylor learned sign language), first as a lover and then as a friend, until Wilson’s death in 2004. Although men and women often dance interchangeably in Taylor’s ballets, especially in works with large numbers of dancers, only in rare instances is there actual same-sex partnering. Of Piazzola Caldera (1998), a work Taylor described as “about physical sex,” he said, “I cast seven men and five women knowing that at times we were going to have to have same-sex partnering because, again, it’s another human trait” . A homoerotic sub-text can also be seen in the “I Can Dream, Can’t I” section of the World War II themed Company B (1991), choreographed to music by the Andrews Sisters, where a woman dreams of her boyfriend who is seen in the background far more interested in another man.

During his career, Taylor received many prestigious awards, including the Kennedy Center Honors, the National Medal of the Arts, and induction into France’s Legion d’Honneur. In 2014, Taylor established Paul Taylor American Modern Dance, a new company that would present his work and that of other important Modern dance choreographers, as an effort to insure that these works survived the death of their choreographers.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (May 2021).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: unknown

- Year Built: c. 1822

Sources

Alastair Macaulay, “A Virtuoso Who Gave Wings to Modern Dance,” The New York Times, August 31, 2018.

Angela Kane, “A Catalogue of Works Choreographed by Paul Taylor,” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, 14 (Winter 1996), 7-75.

Angela Kane, “Paul Taylor: Chronology and Dancers (1954-1996),” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, 14 (Winter 1996), 5-7.

Angela Kane, “Through a Glass Darkly: The Many Sides of Paul Taylor’s Choreography,” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, 21 (Winter 2003), 90-129.

Brian Bromberger, “Remembering Paul Taylor,” Bay Area Reporter, September 12, 2018.

Josh Barbanel, “A Choreographed Move,” The New York Times, August 2, 2009.

Paul Taylor, Private Domain: An Autobiography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987).

Robert Gottlieb, “Remembering Paul Taylor, Dancemaker of Genius,” New York Observer, August 31, 2018.

Sarah Kaufman, “Paul Taylor, Prolific Modern Dance Choreographer, Dies at 88,” Washington Post, August 30, 2018.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?