Paul Cadmus & Jared French Residence & Studio

overview

In 1935, the top floor of this Greenwich Village rowhouse became the home and studio of two of America’s most important mid-20th-century artists, Paul Cadmus and Jared French, both of whom frequently employed gay or homo-erotic imagery.

It remained Cadmus’s home and studio through the 1950s and was where many of his major paintings were completed.

History

Paul Cadmus (1904-1999) grew up in a poor but artistic family in Manhattan. In 1926, at the Art Students League, Cadmus met the New Jersey-born artist Jared French (1905-1988). They became lovers and life-long friends, with French persuading Cadmus to become a full-time artist.

In 1933, Cadmus moved into an apartment at 54 Morton Street (it is not clear if French lived there as well), where he remained for two years. During this period, Cadmus painted The Fleet’s In (1934), a satirical study of lustful sailors and their pickups on Riverside Drive. The painting propelled Cadmus to national renown when a Navy admiral removed it from an exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., clearly taking issue with a gay man in the painting picking up a sailor, even though commentary focused on the sailors and women. Cadmus said, “I owe the start of my career to the Admiral who tried to suppress it.” As historian George Chauncey describes it,

The man offering a cigarette to the sailor has the typical markers of a fairy: bleached hair, tweezed eyebrows, rouged cheeks, and red tie. The sailor’s eyes suggest he knows exactly what is being offered along with the smoke.

In 1934, Cadmus also painted Greenwich Village Cafeteria, an exaggerated image of the raucous goings-on at Stewart’s Cafeteria that includes a gay man looking over his shoulder beckoning any [male] viewer to join him in the bathroom.

In 1935, Cadmus and French rented a combined apartment and studio on the third floor of 5 St. Luke’s Place in Greenwich Village. This was Cadmus’s home and art studio for 25 years. Even after French married artist Margaret Hoening in 1937 and moved to 414 West 20th Street, French continued to share the studio (according to Cadmus, the Frenches eventually purchased the parlor and third floors and they moved into the St. Luke’s building). Indeed, the Frenches and Cadmus were inseparable for many years and the sexual relationship between the two men continued. The three summered together at Fire Island and Provincetown and began taking mostly staged photographs, under the name PaJaMa (an acronym of their first names). Many of these were nude images of gay men in their social circle. Cadmus frequently used French as his model, notably in Gilding the Acrobats (1935).

In c. 1936, both Cadmus and French received commissions for murals in new post offices. One of French’s murals, “Meal Time with the Early Coal Miners” in Plymouth, Pennsylvania, features four well-built, shirtless men and, in the background, the only male frontal nude in a Depression-era public mural. In order to paint their murals, the artists needed a large, well-lit space, so in 1937 they added a rooftop skylight to the center of their apartment/studio.

In 1937, Cadmus and French met Lincoln Kirstein and they became part of a wider gay artistic social circle. Kirstein was then involved with establishing a ballet company in America and Cadmus designed the costumes for Filling Station, a ballet with music by Virgil Thomson. The costume for the lead male character was entirely transparent. French designed the highly eroticized costumes for Billy the Kid, to music by Aaron Copland.

The scope of Cadmus’s social circle is evident in Stone Blossom: A Conversation Piece (1939-40), a portrait of the threesome Monroe Wheeler, Glenway Wescott, and George Platt Lynes. During this period, French began creating enigmatic paintings and drawings with stylized, statue-like muscular men in ambiguous relationships with other men or with women, generally set in empty landscapes. Little is known about the meaning of these works since French rarely spoke about his art, except, as historian Nancy Grimes relates, that they exemplify “man’s inner reality.” In 1939, the Renaissance technique of egg tempera was introduced into French’s work, beginning with Washing the White Blood from Daniel Boone and continuing in such works as Evasion (1947), both of which display French’s hyper-stylized male figures.

Cadmus soon also adopted egg tempera, which he liked for “its delicacy and its linear quality and the freshness of its color.” His final oil painting was another controversial work, Herren Massacre (1940). Commissioned by Life magazine, the painting is based on a 1922 event in Herren, Illinois. Life refused to print it, possibly because of the graphic manner in which Cadmus portrayed striking union workers murdering strikebreakers. The idealized, Renaissance-inspired dead and dying figures, virtually thrust into the viewers’ space, create a disturbingly homoerotic work. This work and French’s Murder (1942), with its ten nude male figures, were included in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1943 exhibition “American Realists and Magic Realists.”

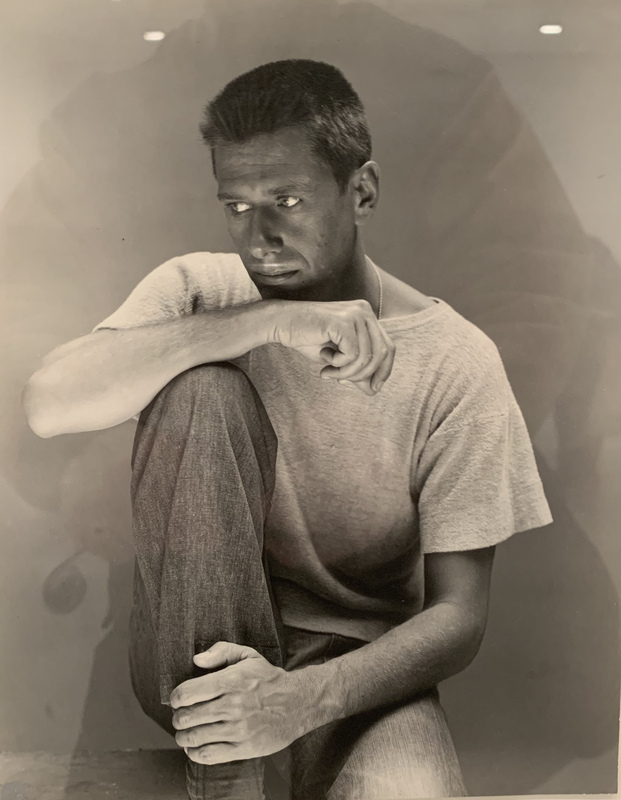

In 1944, Cadmus met George Tooker (1920-2011) and they became lovers. Tooker also worked in egg tempera and created enigmatic paintings that often border on surrealism. While Cadmus and French continued to share the St. Luke’s Place studio, Tooker rented one nearby. Referring to this arrangement, Cadmus quipped, “I had Jerry in the daytime and George at night.” George Platt Lynes took several photographs in the studio that subtly illustrate the complexity of the relationship between Cadmus, French, and Tooker. In one, Tooker is sitting alone in a chair beside a mirror in which Cadmus and French, clearly seen as a couple, are reflected. Lynes also took many individual photographs of the three artists, as well as images of Cadmus and French together. In 1947, when Cadmus was at the beach, his friend, writer E. M. Forster, stayed at the St. Luke’s Place apartment. In 1949, Tooker ended his relationship with Cadmus, largely because of the constant presence of the Frenches.

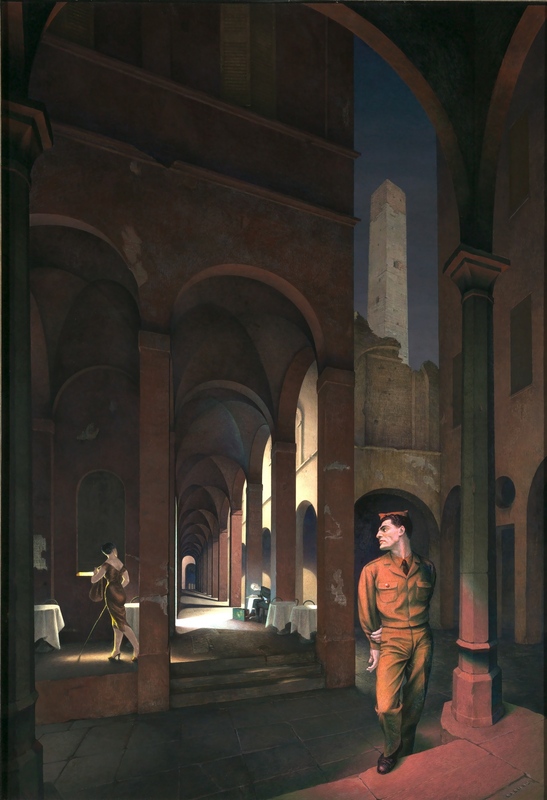

Cadmus believed that his best work was Night in Bologna (1953), a human triangle set beneath the arcades of Bologna, with an Italian soldier eyeing a prostitute who stares at an American tourist, whose interest lies in the soldier. Cadmus was also one of the first artists to sensitively examine gay men in everyday settings that balance domesticity or work life with a level of eroticism. This is most evident in The Bath (1951), which shows two naked men in their tenement bathroom preparing for the day.

Cadmus’s complex relationship with the Frenches subsided in 1951 when they moved to Rome and Jared fell in love with an Italian. Cadmus lived and worked on St. Luke’s Place until the building was sold in the late 1950s. He settled on Remsen Street in Brooklyn Heights in 1961 before moving to Weston, Connecticut, in 1975 with Jon Anderson, the subject of scores of nude drawings. Having met in 1964, they lived together for the remainder of Cadmus’s life.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (February 2025).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown

- Year Built: 1851-52

Sources

Bryan Martin, “Paul Cadmus and the Censorship of Queer Art,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2021, bit.ly/3CNgt71.

David Leddick, Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein, and Their Circle (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000). [source of “I had Jerry in the daytime…” quote, 185]

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994). [source of pull quote, 64]

Jarrett Earnest, ed., The Young and Evil: Queer Modernism in New York, 1930-1955 (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2019).

Jeffrey Wechsler, The Rediscovery of Jared French (New York: Midtown Payson Galleries, 1992).

Jonathan Weinberg, “Cruising with Paul Cadmus,” Art in America 80 no. 11 (November 1992): 101-8.

Josephine Gear, “Cadmus, French, & Tooker: The Early Years,” New York: Whitney Museum of Art at Philip Morris, 1990.

Lincoln Kirstein, Paul Cadmus (New York: Imago Imprint, 1984).

Nancy Grimes, “French’s Symbolic Figuration,” Art in America 92 no. 11 (November 1992): 110-15. [source of Grimes quote, 111]

Nancy Grimes, Jared French’s Myths (San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1993).

“Paul Cadmus: The Male Nudes,” New York: D C Moore Gallery, 2024.

“Paul Cadmus: The Queer Artist Who Undressed America’s Soul,” Prism & Pen, December 8, 2024.

Philip Eliasoph, Paul Cadmus: Yesterday & Today (Oxford, Ohio: Miami University Art Museum, 1981), bit.ly/40KFB6v.

Smithsonian Archive of American Art, “Paul Cadmus: Oral History Interview with Judd Tully,” March 22-May 5, 1998, bit.ly/4gzvM0V.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?