135th Street Branch, New York Public Library

now part of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

overview

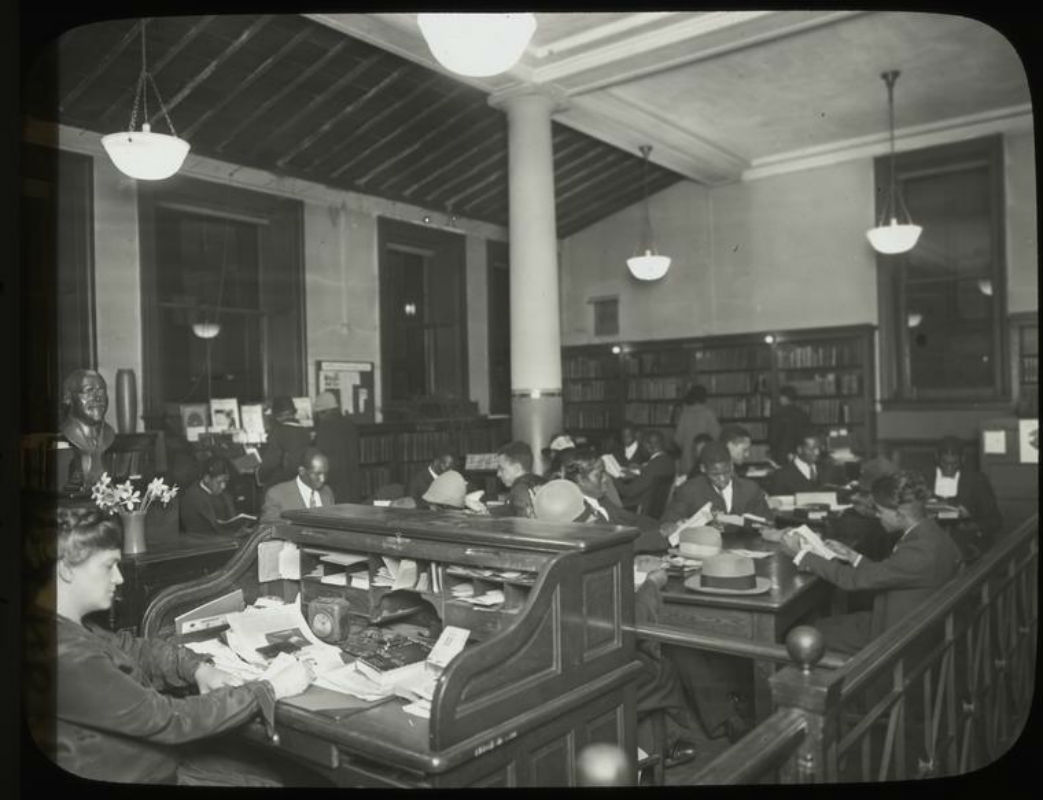

During the Harlem Renaissance, the New York Public Library’s 135th Street Branch served as an intellectual and artistic center for African Americans, including the likes of Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Claude McKay.

In the mid-1920s, the works of these gay poets were included in the newly formed Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints, which ultimately became part of the renowned Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

History

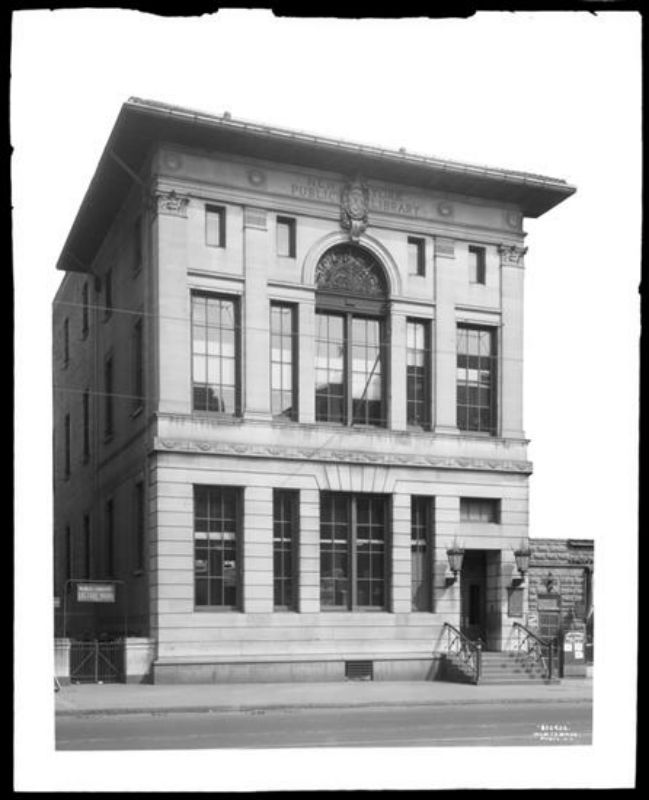

The third of 12 Carnegie libraries designed by the preeminent firm of McKim, Mead & White for the New York Public Library (NYPL), the 135th Street Branch opened in 1905. Within the next ten years, African Americans started to move to Harlem in large numbers. Under newly-appointed white librarian Ernestine Rose in 1921, the 135th Street Library made significant changes to better serve a burgeoning Black community. That same year, it became the first NYPL branch to have an integrated staff. Nella Larsen began working here in 1922; while there is currently no documentation to suggest that she was a lesbian or bisexual, her book Passing (1929) — about two light-skinned Black women passing for white — has been interpreted and taught by some scholars as a lesbian-themed text.

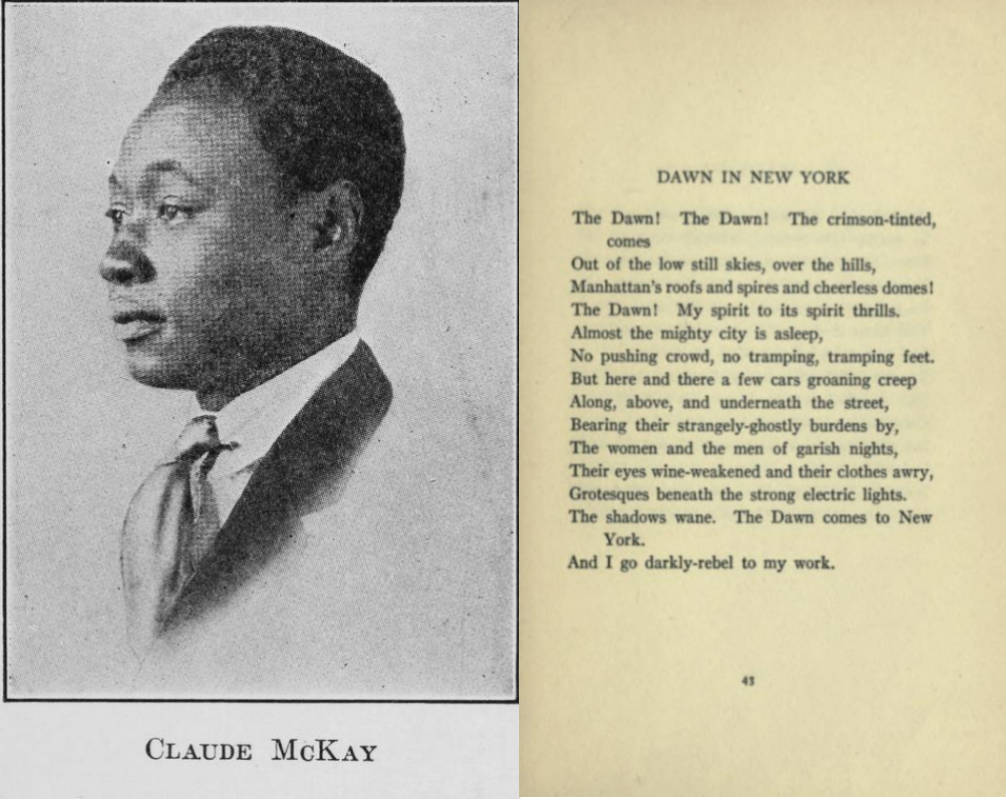

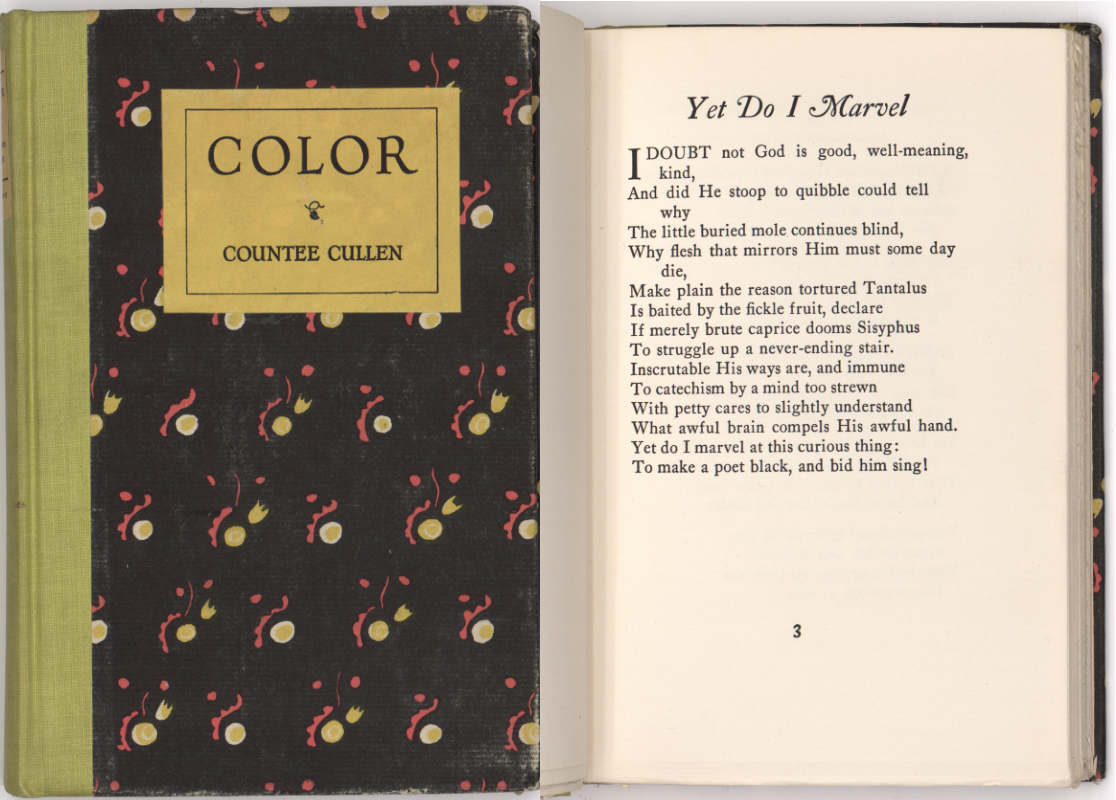

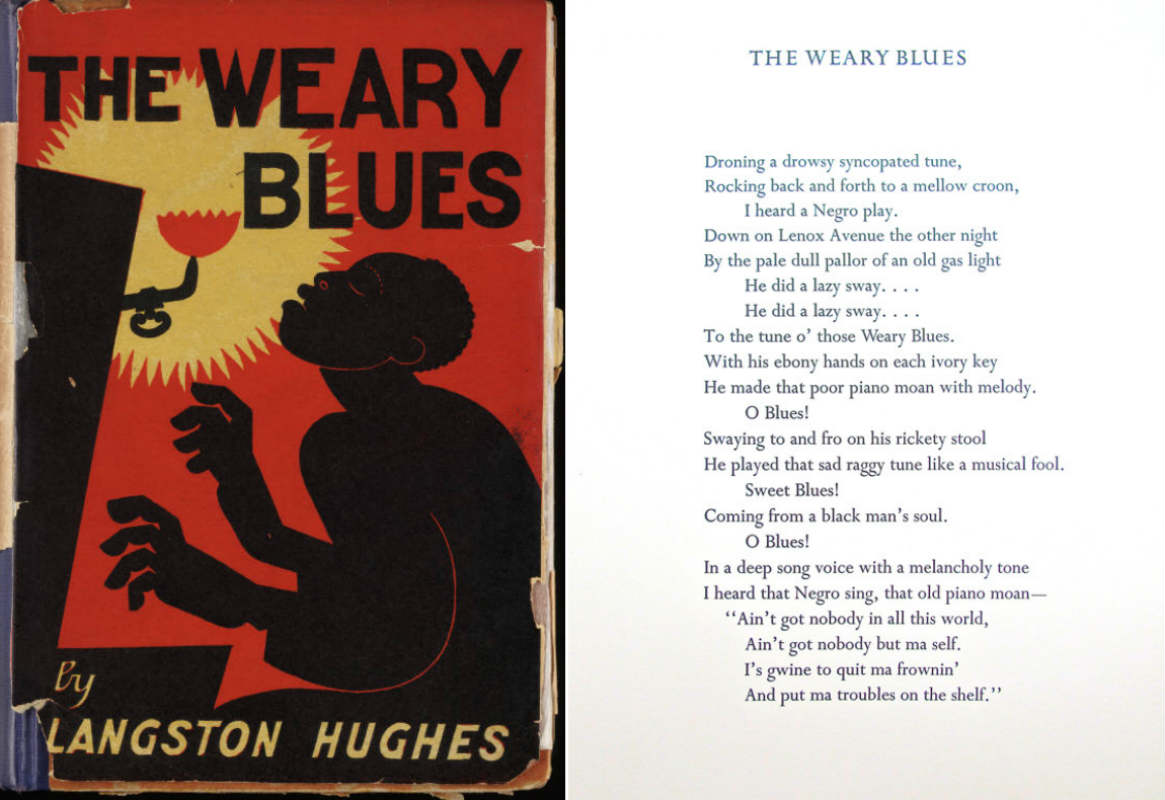

The 135th Street Branch, with its literary gatherings, art exhibitions, theatrical and musical productions, and lectures, was known as “the place to go” during the Harlem Renaissance. Importantly, the library provided a rare public platform for Black artists, writers, and performers as well as the opportunity to share their work with audiences of color. A young Langston Hughes made a point to visit the library the day he arrived in Harlem in 1921 (he later wrote about it in his 1963 essay “My Early Days in Harlem”). Other Harlem Renaissance luminaries who frequented the branch included poet Countee Cullen (who met Hughes here), performer Florence Mills, poet Claude McKay and writer Eric Walrond, the latter two of whom also reserved space here to work. In 1926, the Krigwa Players Little Negro Theatre, which included playwright Harold Jackman, performed plays by, about, and for people of color in the library’s basement. (The American Negro Theatre still performs here.)

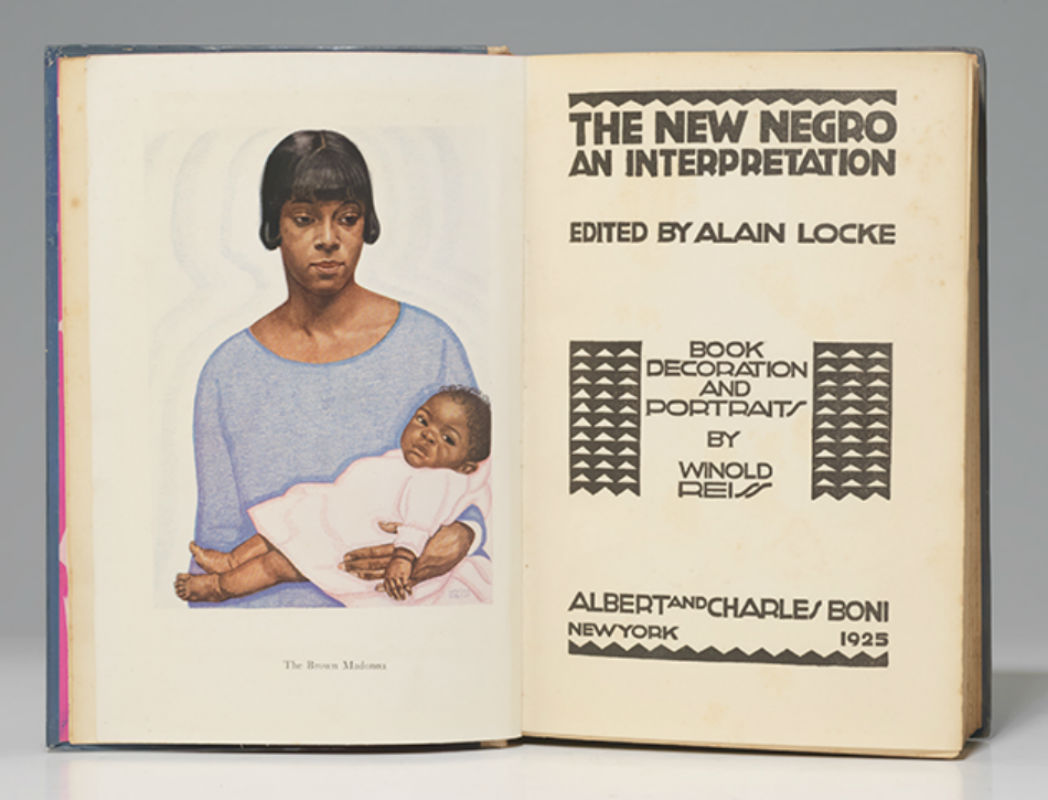

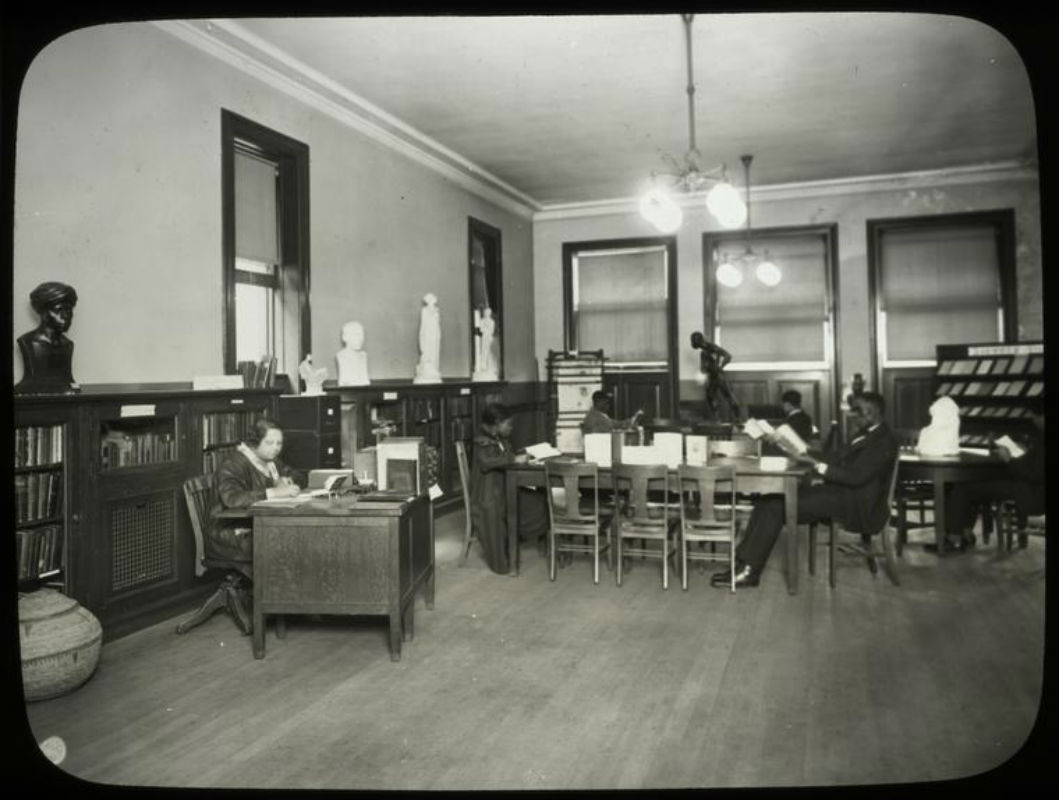

The Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints — the precursor to today’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture — was formed on the third floor in 1925; today it is considered the library’s most significant legacy. Aside from Arturo Schomburg’s large collection that he donated in 1926, some of the earliest acquisitions included McKay’s Harlem Shadows (1922), Cullen’s Color (1925), writer Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925), and Hughes’s The Weary Blues (1926). As scholar Sarah A. Anderson noted, “The library provided a space in which a people, long denied an understanding and appreciation of their own history and culture, could explore what it meant to be black.” Indeed, its holdings would later have a profound influence on a young James Baldwin.

I went to the 135th Street library at least three or four times a week, and I read everything there. I mean, every single book in that library. In some blind and instinctive way, I knew that what was happening in those books was also happening all around me. And I was trying to make a connection between the books and the life I saw and the life I lived.

In 1972, the branch became one of four designated NYPL research libraries. The collection ultimately moved to the neighboring Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The Countee Cullen Branch is located on the north end of the block.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (February 2018).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: McKim, Mead & White

- Year Built: 1904-05

Sources

Amanda Casper, “Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Philadelphia: National Park Service, Northeast Regional Office, October 15, 2015).

David Levering Lewis, When Harlem Was in Vogue (USA: Oxford University Books, 1981).

Paula Martinac, The Queerest Places: A Guide to Gay and Lesbian Historic Sites (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1997).

Salamishah Tillet, “The Real Surprise of ‘Passing’: A Focus on Black Women’s Inner Lives,” The New York Times, November 19, 2021, nyti.ms/3H9i4k3.

Sarah A. Anderson, “‘The Place to Go’: The 135th Street Branch Library and the Harlem Renaissance,” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, Vol 73, No. 4 (October 2003), pp. 383-421.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?