Miguel Braschi & Leslie Blanchard Residence

overview

In 1986, following the death of his partner Leslie Blanchard, Miguel Braschi received an eviction notice from the landlord of the apartment they had shared for ten years because he was not on the lease and was not recognized as a member of Blanchard’s family.

Braschi fought the eviction in court and ultimately won in 1989, paving the way for the legal rights of other non-traditional families in New York and the nation.

History

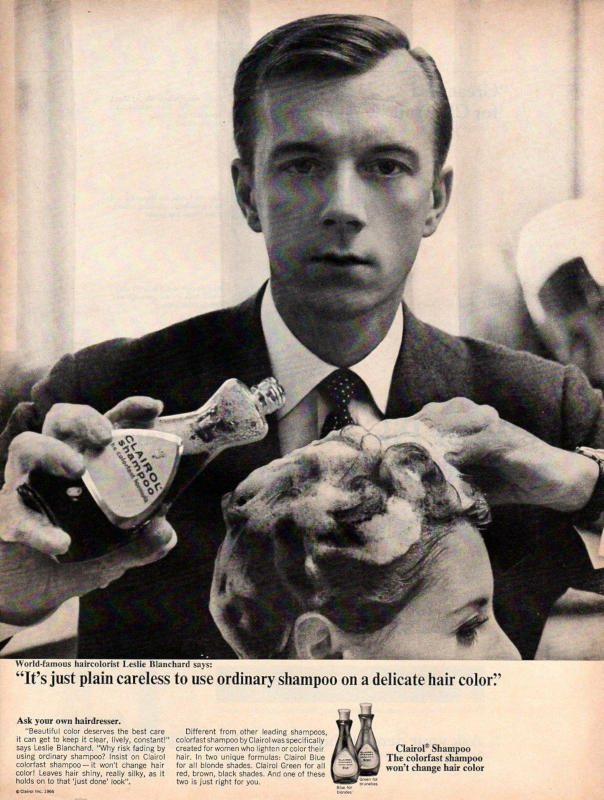

In 1976, Miguel Braschi (1956-1990) moved into the one-bedroom, rent-controlled apartment of his partner Leslie Blanchard (1934-1986), in the handsome building at 405 East 54th Street. The two lived together as a couple until Blanchard’s death from AIDS ten years later. Blanchard was a successful hair stylist with a salon, known as the Private World of Leslie Blanchard, at 19 East 62nd Street that catered to celebrities and socially prominent men and women. Blanchard’s photograph was also prominently featured in a series of magazine ads for Clairol. He met Braschi at a gay bar in Braschi’s native San Juan, Puerto Rico.

A few weeks after Blanchard’s death, Braschi began receiving letters from the building’s owner, Stahl Associates, ordering him to vacate the apartment since his name was not on the lease and, as a gay partner, he was not legally recognized as a member of Blanchard’s family. Braschi chose to fight the impending eviction. He won his case at the New York Supreme Court, but the victory was overturned at the Appellate Division. At this point, Bill Rubinstein, working at the American Civil Liberties Union’s Lesbian and Gay Rights Project, took over the case, aided by amicus briefs submitted to the Court of Appeals, New York State’s highest court, by the Legal Aid Society, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, and others. In 1989, the court ruled four to two in Braschi’s favor. The majority decision stated clearly that:

The intended protection against sudden eviction should not rest on fictitious legal distinctions or genetic history, but instead should find its foundation in the reality of family life.

Braschi’s victory recognized that non-traditional families had a right to succeed rent-controlled apartments. This was later extended to all rent-regulated apartments. The recognition of Braschi and Blanchard as a family influenced later LGBT rights legal cases in New York and elsewhere in the United States.

Sadly, Braschi died of AIDS shortly after the case was resolved.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (May 2021).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: George & Edward Blum

- Year Built: 1929-30

Sources

Carlos A. Ball, From the Closet to the Courtroom: Five LGBT Rights Lawsuits that Have Changed Our Nation (Boston: Beacon Press, 2010).

Enid Nemy, “Beauty from Head to Toe,” New York Magazine 4 (January 11, 1971), 59-62.

Museum of the City of New York, “Miguel Braschi: Fighting for Same-Sex Couples to Be Recognized as Families,” Hidden Voices: LGBTQ+ Stories in American History, 173-175.

Paris R. Baldacci, “Protecting Gay and Lesbian Families from Eviction from Their Homes: The Quest for Equity for Gay and Lesbian Families in Braschi v. Stahl Associates,” Texas Wesleyan Law Review 13 (2007), 619-644.

Paris R. Baldacci, “Pushing the Law to Encompass the Reality of Our Families: Protecting Lesbian and Gay Families from Eviction from Their Homes – Braschi’s Functional Definition of ‘Family’ and Beyond,” Fordham Urban Law Journal 21 (1994), 973-995.

William J. Rubinstein, “We are Family: A Reflection on the Search for Legal Recognition of Lesbian and Gay Relationships,” Journal of Law and Politics 8 (Fall 1991), 89-105.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?