Maurice Kenny Residence

overview

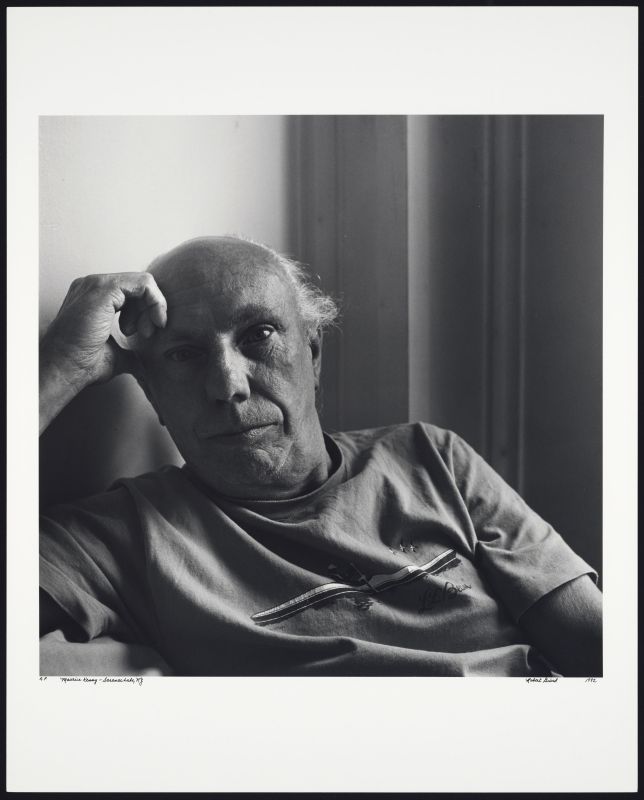

Poet Maurice Kenny, widely regarded as one of the first Native American writers to publish literature exploring Two-Spirit identity, rented a studio apartment on the top floor of this Brooklyn Heights rowhouse from 1967 to 1987.

While living here, Kenny entered one of his most prolific and transformative periods as a writer, publishing his first poetry with overtly queer and Native themes.

History

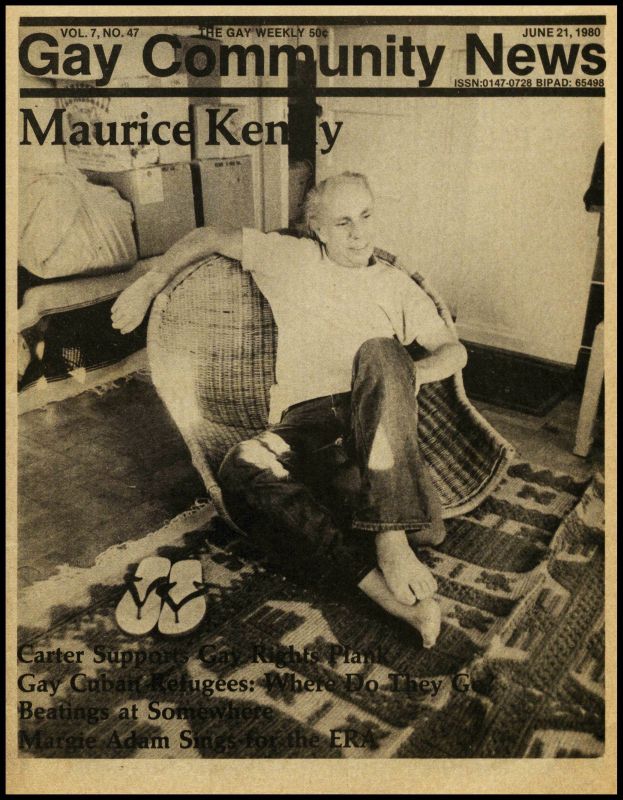

Poet Maurice Kenny (1929-2016; tribal nation: Mohawk/Seneca), who scholar Will Roscoe called “the recognized elder of gay Native writers,” was born in Watertown, New York. Through his poetry, Kenny explored themes of homosexual love, desire, and intimacy, weaving together his personal experiences and cultural heritage to explore the complexities of being a gay Native American in a society that marginalized both identities.

Kenny published his first collection, Dead Letters Sent (1958), while studying under eminent poet Louise Bogan at New York University, crediting her as a “guiding light” who helped him “return home” and explore his roots. The collection included an introduction by another mentor, Samuel Loveman, who Kenny met while managing a Marboro Books near Carnegie Hall and came to consider “the most vivid and extraordinary individual who distinctively affected my writing.”

During this time, from 1957 to 1962, Kenny lived in a boarding house at 66 Morton Street, in Greenwich Village, where he befriended author Willard Motley. He then traveled to Mexico (as Motley’s secretary), the Caribbean, and Chicago, eventually moving into a Brooklyn Heights studio apartment at 62 Clark Street in 1967. Kenny “filled the room with bright colors…magenta, cobalt, acid greens, melon, and lemon, all the colors [he] had grown to love in Mexico and the Caribbean.”

Soon thereafter, Kenny began writing about his heritage and sexuality, galvanized by the Occupation of Alcatraz in 1969, the Wounded Knee Occupation in 1973, and the time he spent in San Francisco with Gay American Indians co-founders Barbara May Cameron (Lakota) and Randy Burns (Paiute). These poems were included in many of the publications that proliferated during the post-Stonewall gay cultural renaissance and the concurrent Native American Renaissance.

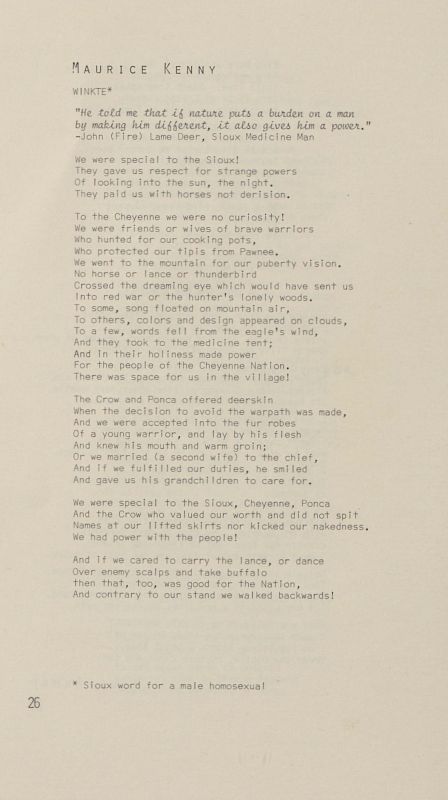

In 1976, Gay Sunshine published Kenny’s “Tinseled Bucks: A Historical Study of Indian Homosexuality.” In the “silence-shattering article,” Kenny reclaimed the power Two-Spirits had historically held, outlining how settler colonialism repressed knowledge of their existence and perpetuated homophobia in Native communities. Its poetic counterpart was “Winkte” (the Lakota term for Two-Spirit people), first published in ManRoot in 1977. In recognizing Kenny with a Native Writers’ Circle Lifetime Achievement Award, Craig Womack (Creek-Cherokee) spoke of the profound impact the poem had on him:

In terms of my own personal revolution, it was part of a growing intellectual epiphany as a Native gay man that allowed me to imagine myself outside a context of sin and shame.

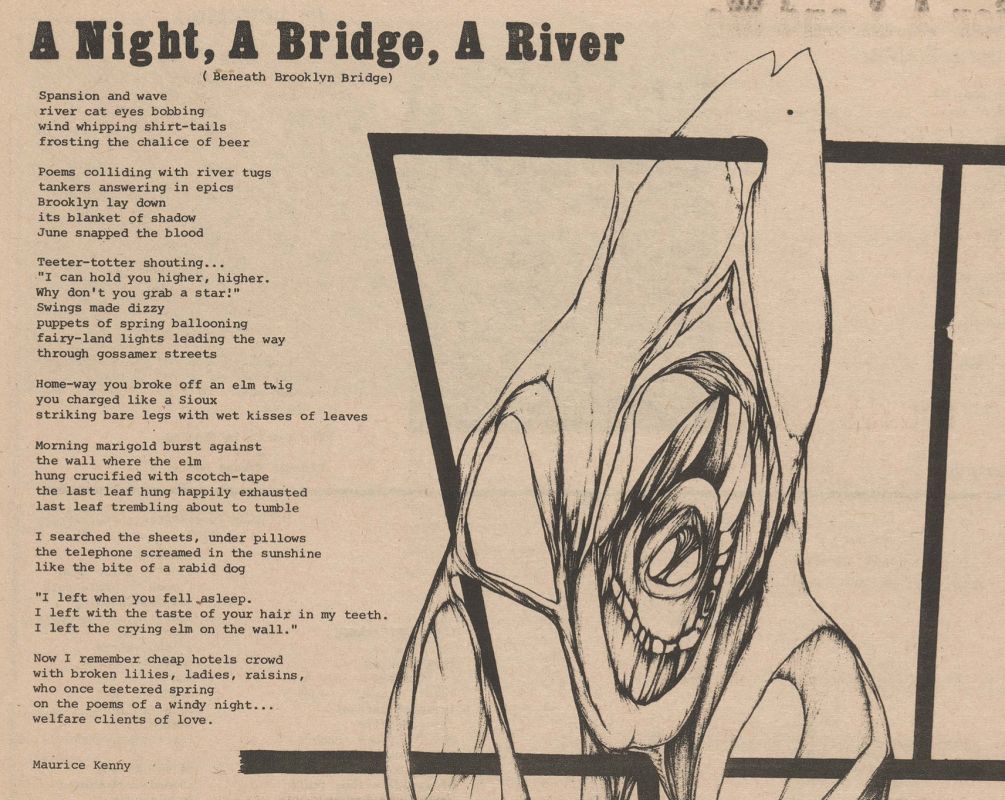

Kenny’s poems also appeared in Fag Rag and Andrew Bifrost‘s Mouth of the Dragon, most of which were later included in Only as Far as Brooklyn (1979), Kenny’s first collection with overtly homosexual themes. In many, he channeled past LGBT poets, honoring their contributions while positioning himself within a broader tradition of queer literature. He imitated ancient Roman poet Catullus, incorporated lines by Edna St. Vincent Millay, and referenced Arthur Rimbaud, Walt Whitman, and Hart Crane. He also parodied the poems of Lord Byron and A.E. Housman, adopting their meter and structure, yet injecting them with overt homoeroticism—a technique that researcher Lisa Tatonetti says was “common not only to post-Stonewall-era gay journals but also to Indigenous oral traditions, which often include trickster stories that…reference sex, the erotic, desire, and genitalia.”

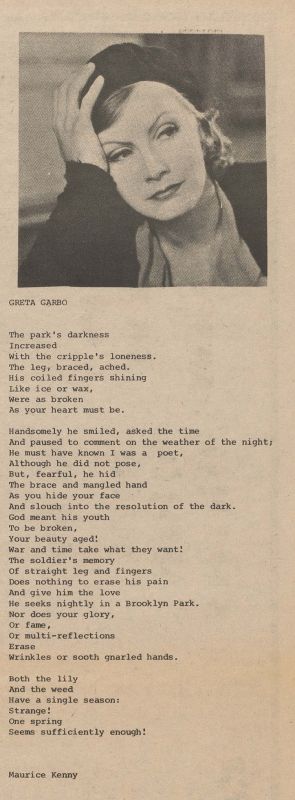

In other poems, Kenny alluded to queer spaces like Hotel St. George or the cruising area beneath the Brooklyn Bridge and to discrete LGBT figures like Greta Garbo. By doing so, Tatonetti argues, “Kenny hails those in the know, both citing and creating community through an articulation of queer geography.”

In 1976, Kenny established Strawberry Press, an exclusively Native American press named in honor of the strawberry’s ceremonial significance as a “symbol of life to Iroquois people.” Through Strawberry Press, Kenny published his own poems and those of upcoming and established Native poets, including Joy Harjo (Muscogee/Creek) and Paula Gunn Allen (Laguna Pueblo).

That same year, Kenny and Josh Gosciak founded Contact/II Press “as an opposing force to the established Pub. [Publisher] Barons.” Though they met at various makeshift offices, “the real work,” Gosciak said, took place in his East Village apartment or in Kenny’s Brooklyn Heights apartment, often involving “a home-cooked meal, some wine, and an all-night reading of poetry, reviews, and ideas for articles or mini-anthologies.” The bimonthly magazine, Contact/II, included work by James Purdy and those involved in the Nuyorican Poets Cafe and ABC No Rio, as well as issues devoted to Audre Lorde and Judy Grahn.

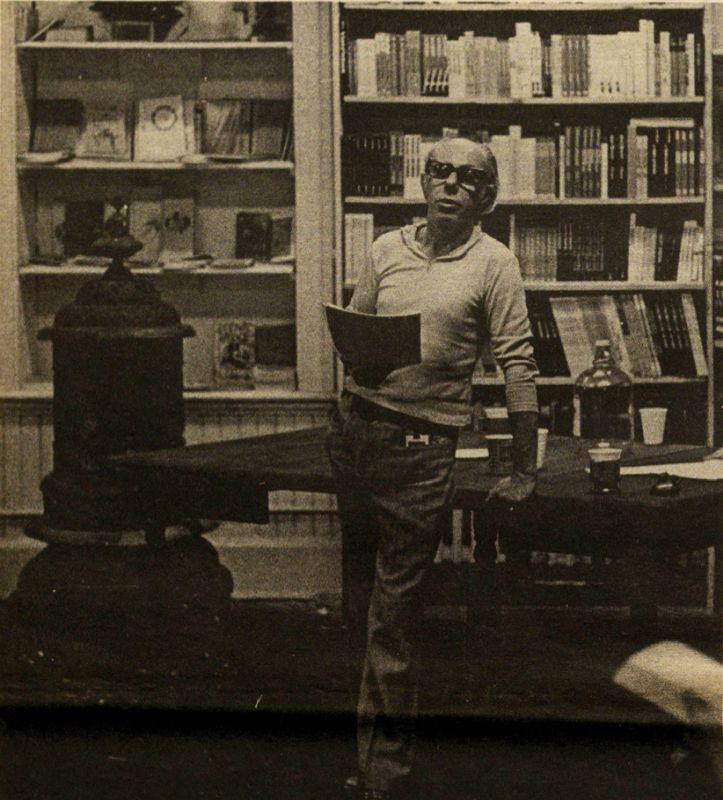

While living on Clark Street, Kenny was twice nominated for the Pulitzer Prize and was involved in the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, in the East Village, and the American Indian Community House, where he was poet-in-residence from 1981 to 1985.

During his final years in Brooklyn, Kenny wrote a series of vignettes describing scenes from his apartment window, published as Last Mornings in Brooklyn (1991). At some point, Kenny temporarily moved next door to 60 Clark Street, then returned upstate to Saranac Lake in 1987.

Entry by Ethan Brown, project consultant (June 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: James Forsyth (owner/developer)

- Year Built: 1853

Sources

Chad Sweeney, “An Interview with Maurice Kenny,” World Literature Today (Norman: University of Oklahoma, May-August 2005), 66–69.

Charley Shiveley and Clover Chango, “Maurice Kenny: Gay Native American Poet,” Gay Community News, June 21, 1980 (accessed December 23, 2022), bit.ly/3GbbLhp.

John Motyka, “Maurice Kenny, Who Explored His Mohawk Heritage in Poetry, Dies at 86,” The New York Times, April 26, 2016, nyti.ms/46d9xdw.

Josh Gosciak, “Contact II, 1970s – 1990s: When Poetry Mattered More,” Poets House, bit.ly/3Ck82fP.

Lisa Tatonetti, “The Native 1970s: Maurice Kenny and Fag Rag” in The Queerness of Native American Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

Maurice Kenny, Angry Rain: A Brief Memoir (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2018).

Maurice Kenny, “The Creative Process: Wild Strawberry,” Wíčazo Ša Review (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, Spring 1985), 40–44.

“Maurice Kenney [sic],” Will Roscoe Papers and Gay American Indians Records (1970-2007), Archives of Sexuality and Gender. [source of pull quote]

Penelope Myrtle Kelsey, ed., Maurice Kenny: Celebrations of a Mohawk Writer (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2011).

“Remembering Maurice Kenny,” Dawnland Voices, May 14, 2017, bit.ly/3MoKKes.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?