Mary E. Dreier & Frances A. Kellor Residence

overview

In 1920, 43 Fifth Avenue was home to Mary Dreier and Frances Kellor, two leading Progressive reformers whose lives were dedicated to labor reform, suffrage, and assisting immigrants and African American women.

History

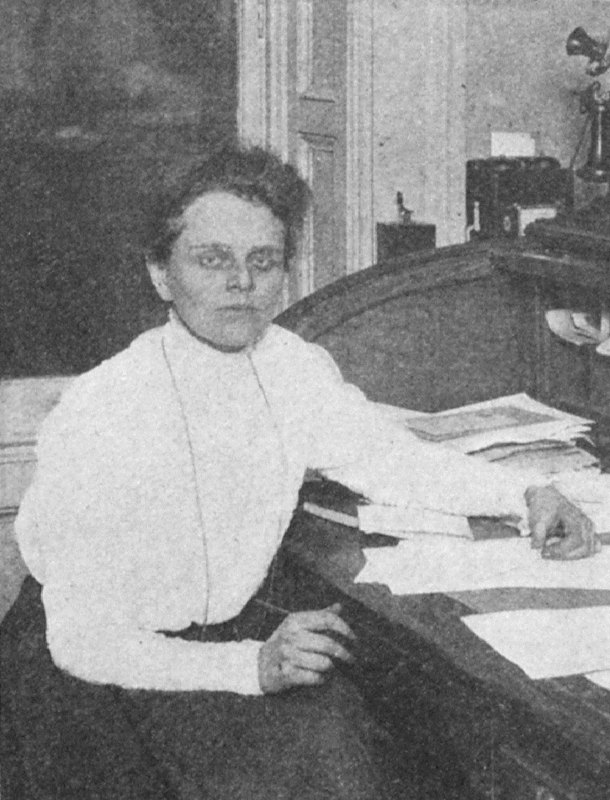

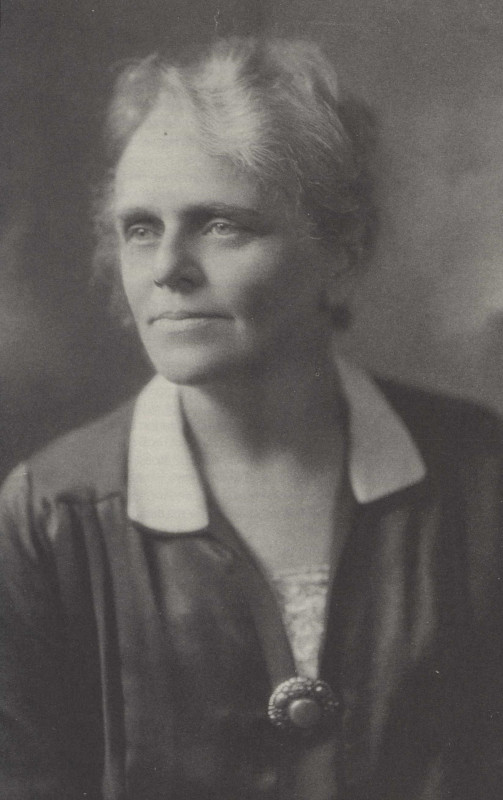

Mary E. Dreier (1875-1963) and Frances A. Kellor (1873-1952) were Progressive-Era social activists, who were part of a large network of lesbian reformers in early twentieth century New York. They met in c. 1903 and, despite their different backgrounds, lived for almost fifty years in what writer Victoria A. Brownworth calls a “passionate and consuming” relationship. Dreier was born into a wealthy family in Brooklyn, while Kellor grew up in poverty in the Midwest. Although well-educated as a child, Dreier did not go to college, while Kellor’s life was transformed by higher education, including a law degree from Cornell, and the study of sociology at the University of Chicago and social work at the New York School of Philanthropy. Dreier was a traditionally feminine woman, while Kellor was a more “butch” figure, often dressing in tailored, masculine clothing. But both were passionate activists who believed in the value of legislation to ameliorate conditions among the poor and downtrodden.

Dreier was especially active in the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), serving as president of the New York chapter (1906-1914), where she worked closely with fellow reformer Helen Marot. Founded in 1903, the League was the first national organization dedicated to fighting for women workers. Its board and membership comprised both women unionists and affluent supporters who fought against sexism in the labor movement. The organization attracted many women who thrived in the homosocial world that it provided.

In 1909, while picketing a shirtwaist factory, Dreier was arrested. When the magistrate realized that she was a wealthy supporter and not a worker he immediately dismissed the case, causing an outcry against the arbitrary treatment of strikers. Dreier was called “a guiding star” by one garment worker and was a mentor to labor leader Rose Schneiderman and, according to historian Ann Schofield, “a spiritual inspiration…patient, tolerant, totally devoted to the working woman’s cause, and one of the most generous people.”

While some of the other wealthy women involved with the WTUL, including Marot, became less focused on working closely with immigrant Jewish and Italian workers, Dreier retained her commitment to improving the lives of all working women and continued to actively support the WTUL financially and with her time. Dreier and other women at the WTUL eventually became disillusioned with the labor movement because of its sexism and turned to both suffrage and advocating for reform legislation as more successful tools for ameliorating conditions of women workers. She was one of the few suffrage leaders who actively sought the inclusion of working women in the movement at a time when most suffrage leaders took a more elitist view. Dreier was a leader in the New York Women’s City Club where she began working with reformers such as Frances Perkins and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Dreier was also concerned about rights for Black women and supported the national meeting where the NAACP was founded in 1909. After the Triangle Waist Company fire in 1911, which killed 146 garment workers, most of whom were women, Dreier was the only woman on the New York Factory Investigating Commission, which successfully recommended many reforms passed by the state legislature. As Schofield has stated:

She didn’t carry a trade union card, but there was no more devoted trade unionist than Mary Dreier.

Kellor initially worked in settlement houses, including Jane Addams‘s Hull House in Chicago and the College Settlement in New York. In the course of her career, she served on many boards and committees and was actively involved with labor reform and efforts to improve the lives of immigrants and African American women. Many of her investigations resulted in influential books and articles, including Out of Work (1904), which explored the exploitative conditions among employment agencies; and The Criminal Negro (1901), which was one of the first works to argue that criminality among Black Americans was not hereditary, but the result of environmental conditions, such as poor educational opportunities, low pay, and discrimination. Kellor was especially concerned about the plight of Black women moving to New York who were exploited and often forced into low-wage service jobs or into prostitution upon arrival in northern cities. She founded the National League for the Protection of Negro Women, which sought to educate women before they left the South and to meet women at transit depots and make sure that they had respectable housing and jobs. Her organization merged with several others in 1911 to form the National Urban League.

Kellor was also focused on improving the living and working conditions of immigrants. She actively fought against nativist efforts to restrict immigration, but also believed that efforts should be made by business and government to assimilate and Americanize new immigrants.

Dreier and Kellor moved many times. In 1920, they shared an apartment at 43 Fifth Avenue, on the corner of East 11th Street. When apart, Kellor wrote highly eroticized letters to Dreier that are preserved at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library. They are buried together at Green-Wood Cemetery.

Additional LGBT History at 43 Fifth Avenue

Before moving to their longtime residence at 2 Fifth Avenue a few blocks south, Edie Windsor and Dr. Thea Clara Spyer lived in an apartment on the eighth floor of 43 Fifth Avenue from 1965, the year they began dating, to 1975. They had met in 1963 at Portofino, a discreet meeting place in Greenwich Village for lesbians on Friday nights. The couple was “harassed” into leaving 43 Fifth Avenue, according to Windsor’s second wife, Judith Kasen-Windsor. Windsor would later go on to become an international icon for LGBT rights as the lead plaintiff in the Supreme Court case United States v. Windsor, which overturned Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act. See Edie Windsor & Dr. Thea Clara Spyer Residence to learn more about the couple’s legacy.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (May 2021; last revised August 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Henry Andersen

- Year Built: 1905

Sources

Allen P. Davis, Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement 1890-1914 (New York: Oxford, 1987).

Ann Oakley, Women, Peace and Welfare: A Suppressed History of Social Reform, 1880-1920 (Chicago: Policy Press, 2018).

Ann Schofield, “To Do & To Be”: Portraits of Four Women Activists, 1893-1986 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997). [source of all Schofield quotes]

Judith Kasen-Windsor, comment on @nyclgbtsites Instagram post, January 4, 2022, bit.ly/3fJOFS8.

Lillian Faderman, To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America – A History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999).

Marilyn Elizabeth Perry, “Mary Elisabeth Dreier,” American National Biography, 1999.

“Mary Elisabeth Dreier,” in Biographical Dictionary of American Labor, Gary M. Fink, ed. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1974), 193-94.

Ralph A. Pearson, “Frances Kellor,” in Biographical Dictionary of Social Welfare in America, Walter I. Tattner, ed. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1986), 449-453.

Susan Amsterdam, “The National Women’s Trade Union League,” Social Service Review 56 (June 1982), 259-272.

Victoria A. Brownworth, “Frances Kellor and the Birth of Multiculturalism,” Erie Gay News, November 2018.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?