Manhattan Plaza

overview

Known as “Broadway’s Bedroom,” Manhattan Plaza is a subsidized housing complex predominantly restricted to people working in the performing arts.

Opened in 1977 shortly before the onset of the AIDS epidemic, Manhattan Plaza was soon the building with the highest per-capita concentration of AIDS-related deaths in the world, but residents responded to the crisis through the Manhattan Plaza AIDS Project, a community initiative that provided care for their neighbors living with AIDS.

History

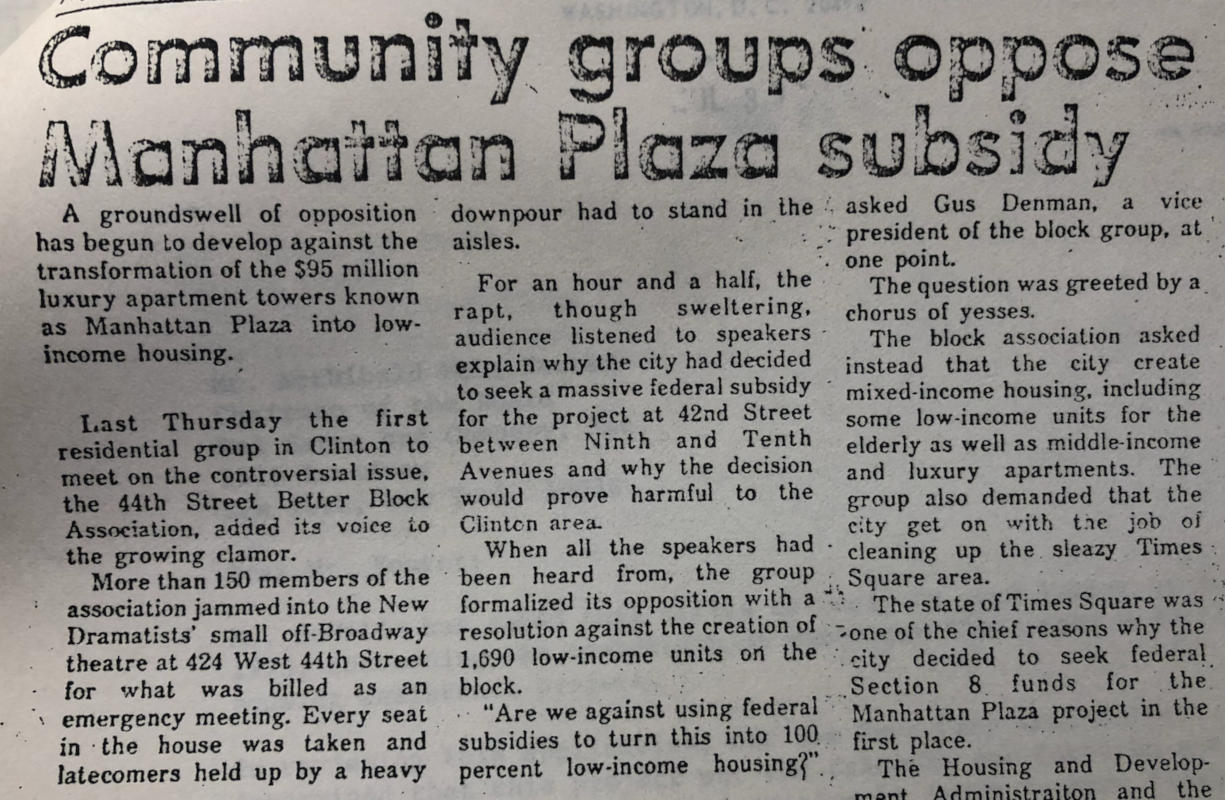

As part of a broader strategy to revitalize the Times Square/Clinton/Hell’s Kitchen neighborhoods, Manhattan Plaza was originally financed under New York State’s Mitchell-Lama program, which provided housing to qualified middle-income families. However, when the development was nearing completion in 1975, the New York City financial crisis and inflation resulted in the need for increased subsidy to ensure affordable rents.

Through a contentious public process, community residents pushed back against a greater subsidy for the complex, which consisted of two apartment buildings with 1,692 apartments, a parking garage, a health club, music and dance practice spaces, and commercial space. Residents were worried that a heavily subsidized project would attract sex workers, drug addicts, and crime to the neighborhood, rather than financially stable professionals.

City leaders and the developer came to the agreement that the City would use some of the scant funding allocated to it through the federal Section 8 program to finish underwriting the complex, but occupancy would be limited to people working in the performing arts, a demographic already rooted in the community due to the proximity of the Broadway theater district, and that also met the income requirements. The New York Times noted that Westbeth Artists Housing, another subsidized complex, could have served as a model for these occupancy restrictions.

Apartments in the building were quickly leased, with 10% of the apartments reserved for people meeting Mitchell-Lama income limits, mostly middle-income families, and the rest more heavily subsidized through the Section 8 program with lower income restrictions. In addition to income restrictions, 70% of the apartments were reserved for people working in the performing arts, 15% for elderly or disabled people, and 15% for current neighborhood residents. This decision was supported by unions like the Actors’ Equity Association and Screen Actors Guild, as it provided new, high quality, and convenient housing for its members.

In the early 1980s, soon after the apartments were occupied, the AIDS epidemic began. Originally focused on meeting the needs of elderly residents, the complex’s Stay Well Center transitioned to providing care for residents living with AIDS. Formed by residents in 1985 after the building’s first AIDS-related death in 1983, the Manhattan Plaza AIDS Project (MPAP) was a cooperative that assigned caregivers to help clean, perform errands and schedule doctors’ appointments for, and provide emotional support to neighbors living with AIDS. Through MPAP, residents created a community built upon a shared interest in the performing arts, providing mutual aid and care when such programs were sparsely funded during the presidency of Ronald Reagan.

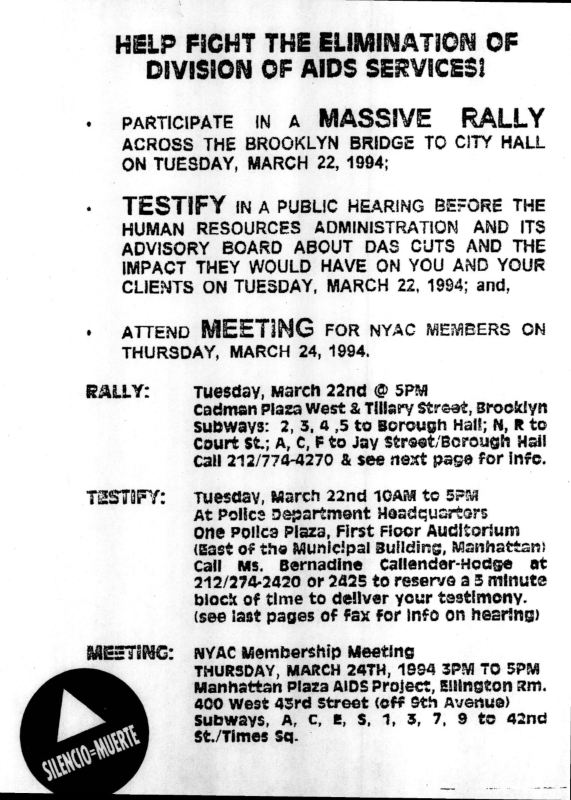

MPAP gradually formalized into an organization with a budget and paid staff, and grew its services to provide educational programming, counseling, information about treatments and therapies, and legal services, expanding operations to other buildings and even at-home care. MPAP partnered with the Gay Men’s Health Crisis to provide training for staff and hosted numerous meetings of AIDS activists and coalitions, including the New York AIDS Coalition and United for AIDS Action.

I don’t know what would have happened without the [AIDS] program here — I would have been dead.

MPAP was the partial brainchild of Rodney Kirk, an Episcopal priest who was hired by the developer to manage and oversee operations of Manhattan Plaza because of his strong sense of community. Kirk laid the groundwork for MPAP by encouraging tenant collectives for shared needs like childcare, helping residents to develop connections with each other. Another major contributor to the formation of MPAP was Marietta LaFargue, a resident who co-founded MPAP after some of her relatives and close friends died from AIDS-related complications.

In 1989 Manhattan Plaza was declared to have the highest AIDS-related per-capita death rate out of any residential building in the country by city officials. Kirk retired after serving two decades as managing director of the complex, and the Stay Well Center transitioned back to elder care and aging-in-place initiatives as AIDS cases declined.

Among the many LGBT residents of Manhattan Plaza have been:

- Barry Hoff, Broadway dresser and member of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis Speaker’s Bureau, and his partner David Carson, an Off-Broadway actor and director, have lived in the building together since 1985.

- Tom Keegan and Davidson Lloyd, openly gay performance artists, lived at Manhattan Plaza from 1977 to 1989, publicly coming out in a 1982 performance titled I’ll Love You Forever.

- James Kirkwood Jr., Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning playwright best known for co-authoring the book for A Chorus Line (1975), lived here in at least 1979.

- Lionel Mitchell, the author of Traveling Light (1980), a novel about a young Black man living in the East Village in the 1960s, lived in the building until his death from complications due to AIDS in 1984.

- Patrick Pacheco, journalist and author of Newsday’s theater column, has lived in the complex since 1992.

- Nick Pippin, founder of the People with AIDS Theatre Workshop, a theater program featuring people living with AIDS, lived in the complex from 1978 until his death in 1990.

- Tennessee Williams, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, was attracted by the complex’s swimming pool and leased a 44th-floor apartment from 1977 to 1980.

Acclaimed performing arts photographer Martha Swope, known for taking photos of numerous LGBT artists, including Lily Tomlin, Tommy Tune, and Michael Bennett, as well as the debut production of The Normal Heart (1985) at the Public Theater, leased an apartment and studio space in the building in 1980.

In addition to being home to people working in the performing arts, Manhattan Plaza became a destination with the West Bank Cafe, opened in 1978. It became a popular hangout for people in the theater and the LGBT community after the creation in 1980 of “Theater Row,” a collection of 10 Off-Off-Broadway theaters on the south side of 42nd Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues. The Cafe’s Downstairs Theater Bar, opened in 1979, had robust cabaret programming that was featured in the first issue of New York Gay Press in 1980 and soon became a venue for people to try out new material. It was renamed the Laurie Beechman Theater in 1988 and has hosted LGBT performers including comedian Sara Cytron and playwright Hilary Sloin, and numerous drag acts.

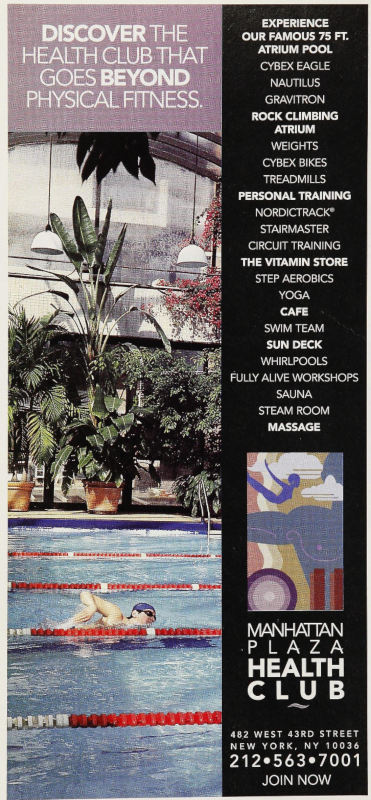

The Manhattan Plaza Health Club was known for its gay clientele, taking out advertisements in The Advocate to attract new members.

Entry by Evan Tuten, project consultant (November 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: David Todd

- Year Built: 1974-1977

Sources

Bruce Lambert, “On the Block Where AIDS Hits Hardest, Residents Rally,” The New York Times, September 8, 1989, 1, 28.

Constance L. Hays, “James Kirkwood, Author of Book For Musical ‘Chorus Line,’ Dies,” The New York Times, April 22, 1989, 88.

David Bird, “For Some Theatre People, Home is Low-Cost Luxury,” The New York Times, September 14, 1979, 29, 45.

Donald Spoto, The Kindness of Strangers: The Life of Tennessee Williams (Boston: Little, Brown, 1985).

Marietta Federici-La Fargue, “AIDS — A Community Answers the Call,” Confronting the AIDS Epidemic: Cross-cultural Perspectives on HIV/AIDS Education (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1997), 153-158.

Nahma Sandrow, “How the Rent Numbers at Manhattan Plaza Add Up,” The New York Times, June 9, 2002, 385.

“Nick Pippin, 35, Dies; Founded AIDS Group,” The New York Times, July 29, 1990, 30.

Patrick Pacheco, “Manhattan Plaza: Guardian Angel in Hell’s Kitchen,” After Dark: The Magazine of Entertainment, February 1978, 71-75.

Rob Waters, “Forged by AIDS, Storied NYC Residence Boosts Aging in Place,” Health Affairs (September 2020), 1472-1478.

Suzanna Bowling, “Meet the Former and Present Residents of Manhattan Plaza,” Times Square Chronicles (accessed August 28, 2022), bit.ly/3ww8WDy.

Stuart Timmons, “Stage Trippers: New York Performers Come West,” The Advocate, October 11, 1988, 18-20.

Tom Keegan and Davidson Lloyd, Story Corps, [Audio Interview], August 25, 2018, bit.ly/3RFESNG.

Wolfgang Saxon, “Rodney Kirk, 67, Director of Manhattan Plaza, Is Dead,” The New York Times, July 17, 2001, 7.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?