Lorraine Hansberry Residence

overview

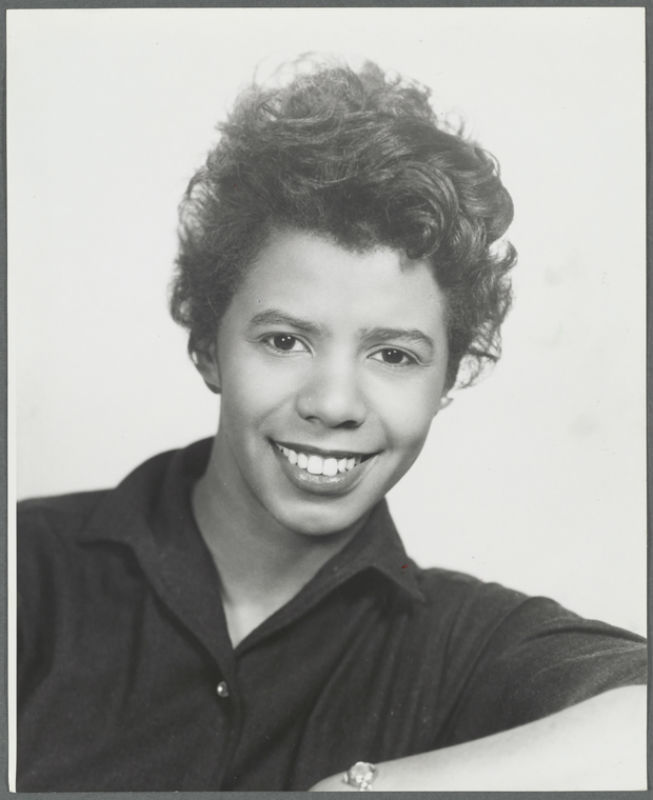

From 1953 to 1960, playwright and activist Lorraine Hansberry resided in the third-floor apartment of this building.

While here, Hansberry lived parallel lives: one as the celebrated playwright of A Raisin in the Sun, the first play by a Black woman to appear on Broadway, and the other, as a woman who privately explored her homosexuality through her writing, relationships, and social circle.

Through the efforts of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, this site was listed on the New York State Register of Historic Places and the National Register of Historic Places in 2021.

History

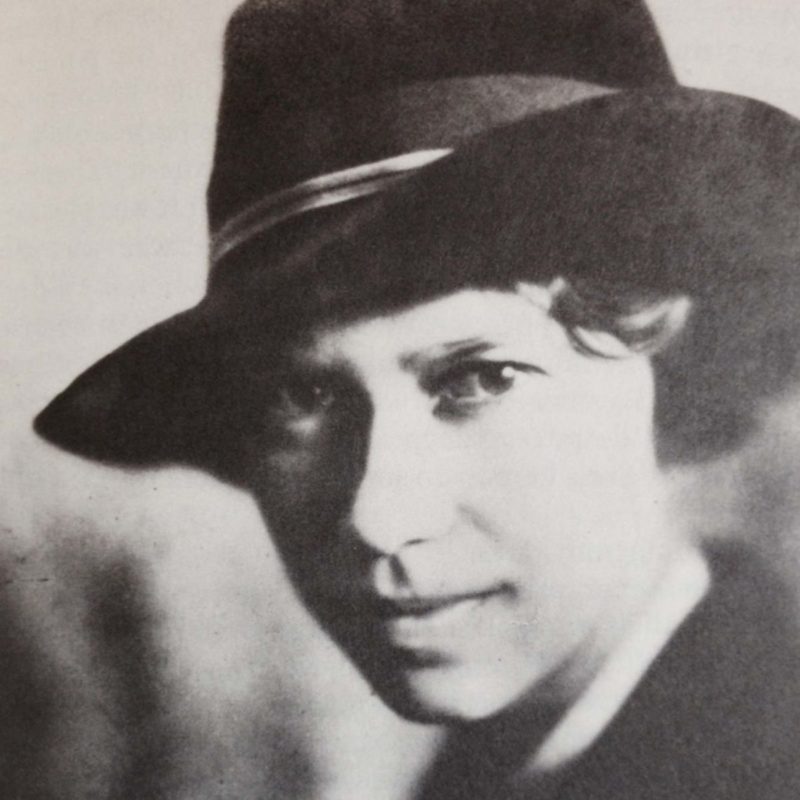

Playwright and activist Lorraine Hansberry (1930-1965) moved to New York City in 1950 where she eventually wrote for the Black newspaper Freedom, based in Harlem, on issues such as racial, economic, and gender inequality. After marrying Jewish songwriter/producer Robert Nemiroff in 1953, the couple moved to the third-floor apartment at 337 Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. (At the time they lived here, the upper two stories had one apartment per floor, which were accessed by the central door located between the two storefronts.) They separated in 1957, though they remained close friends. Hansberry kept the apartment.

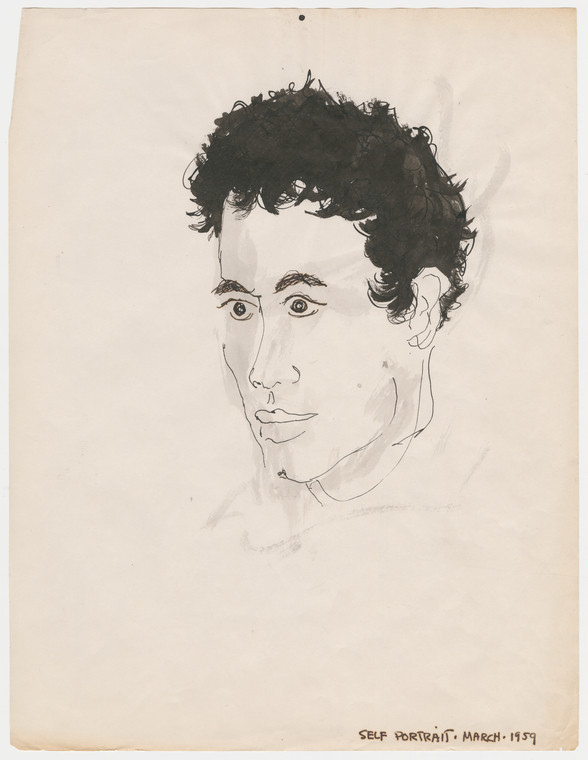

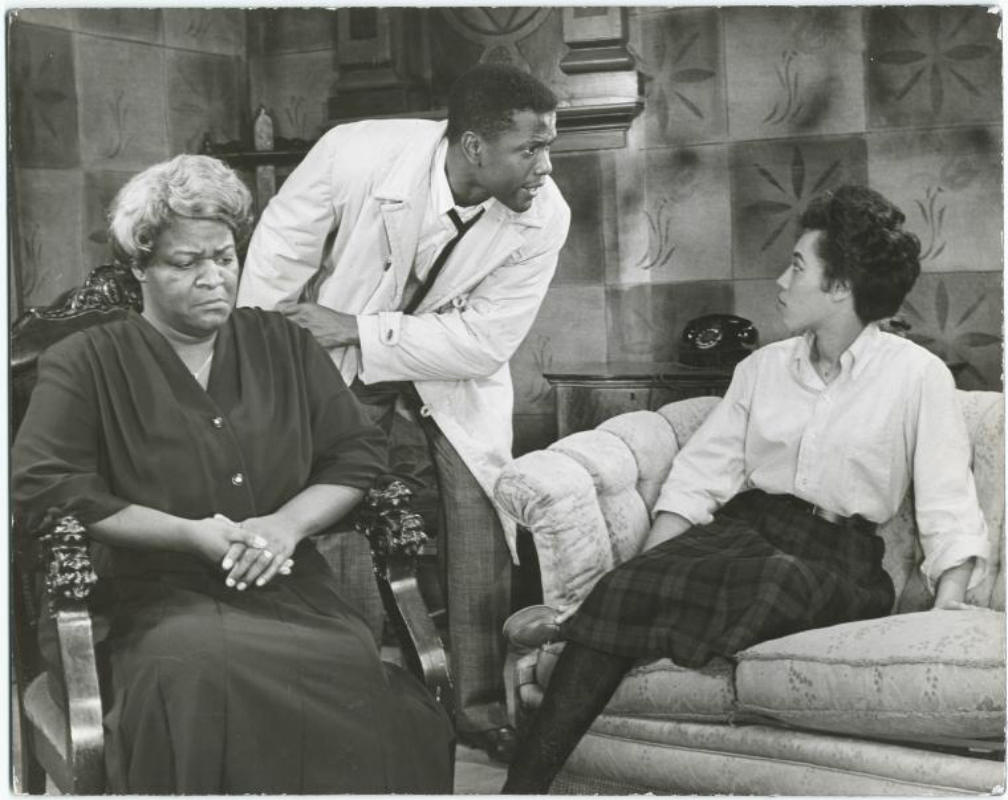

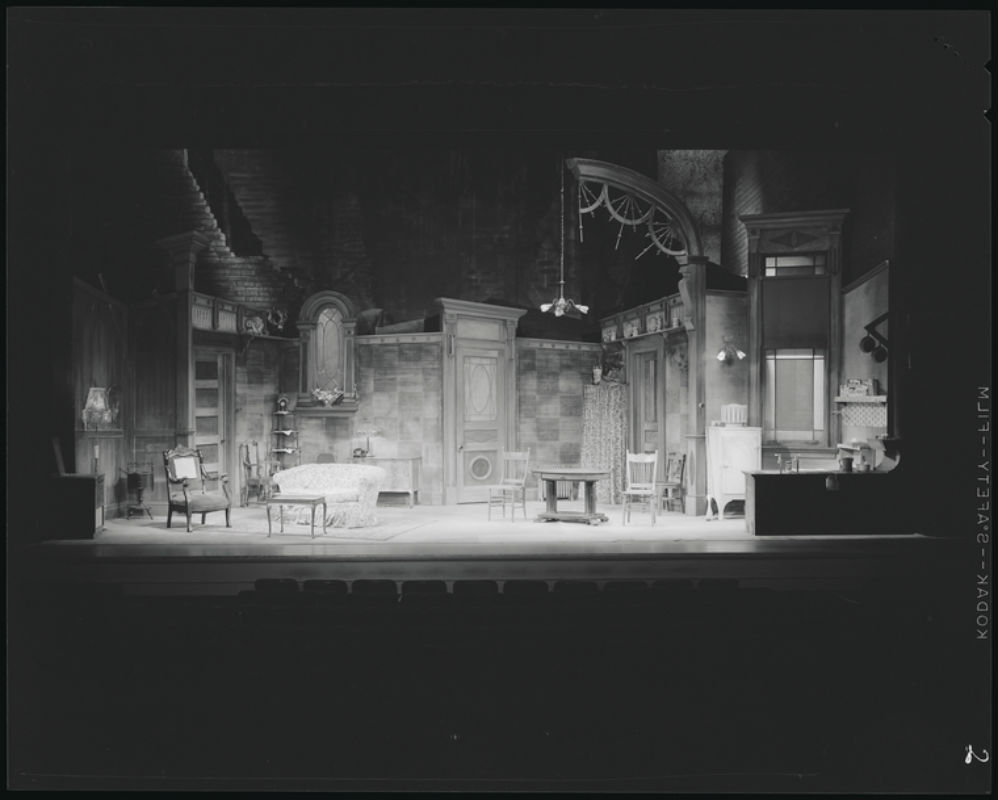

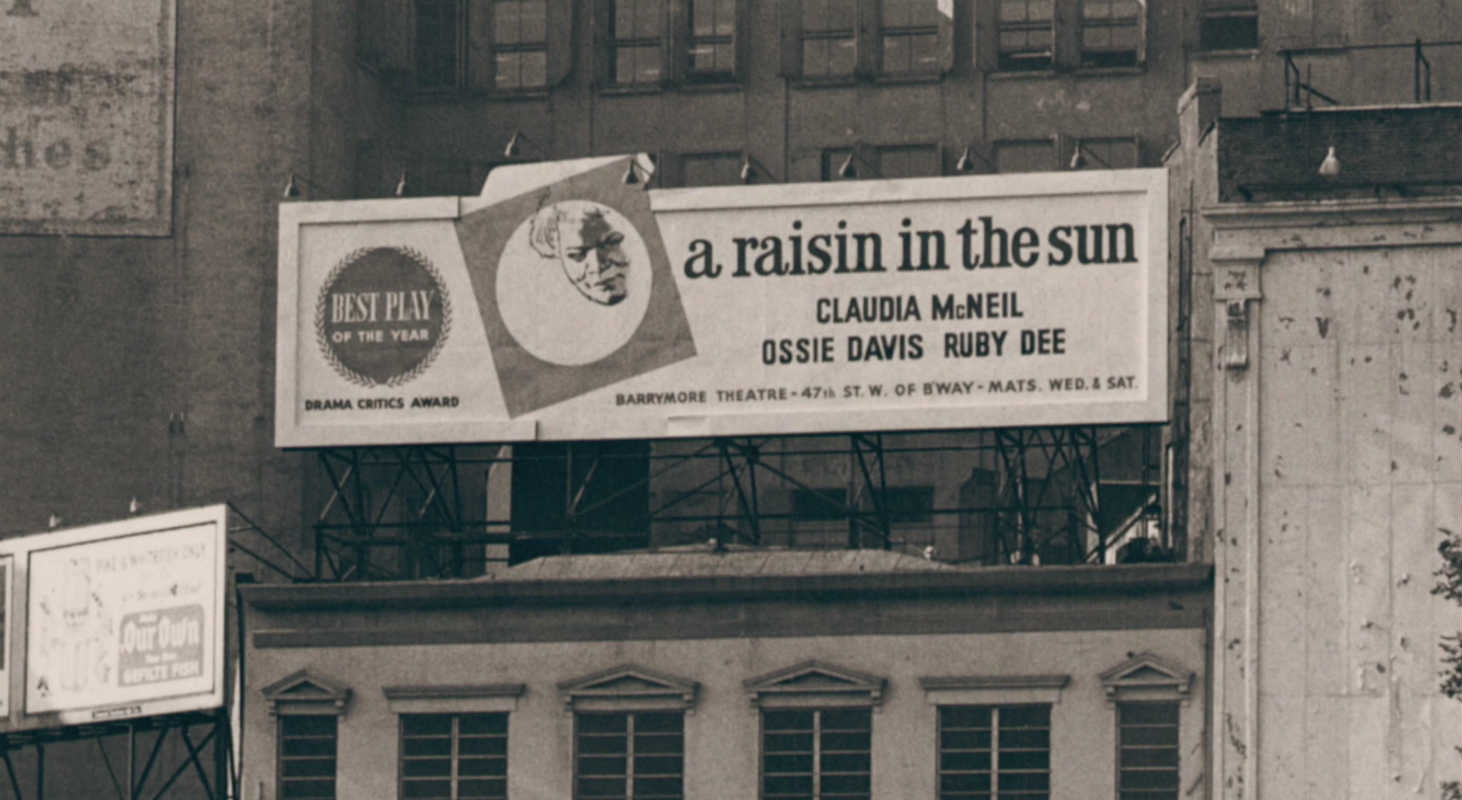

In 1956, Hansberry began to flesh out what would become her best known work: a dramatic play about a Black family in her native, segregated Chicago, called A Raisin in the Sun (the title comes from a line in the Langston Hughes poem “Harlem”). Its New York premiere on March 11, 1959, at the Ethel Barrymore Theater made Hansberry the first Black woman to have a play staged on Broadway. She also became the first African-American playwright, and the youngest playwright ever, to win the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best American Play. An instant celebrity, Hansberry was photographed in her book-lined apartment for Vogue Magazine one month later.

In “Sweet Lorraine” (1969), her friend James Baldwin explained the play’s significance: “I had never in my life seen so many black people in the theater. And the reason was that never before, in the entire history of the American theater, had so much of the truth of black people’s lives been seen on the stage. Black people had ignored the theater because the theater had always ignored them.” The screenplay she wrote for the 1961 movie version was heavily edited by the studio to cater to white audiences.

Even before the play’s success, Hansberry privately identified as a lesbian and wrote letters — signed “L.N.H.” or “L.N.” — to The Ladder, the monthly national lesbian publication of the Daughters of Bilitis. Two DOB co-founders, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, of San Francisco, acknowledged in their 1972 anthology Lesbian/Woman that Hansberry was an early member of the New York chapter and contributed to DOB’s magazine (1956-1972) in its earliest years. Hansberry’s inner conflict regarding societal expectations for women and her same-sex desires are often revealed in these letters:

I wanted to leap into the questions raised on heterosexually married lesbians. I am one of those. How could we ever begin to guess the numbers of women who are not prepared to risk a life alien to what they have been taught all their lives to believe was their natural destiny–AND–their only expectation for ECONOMIC security?

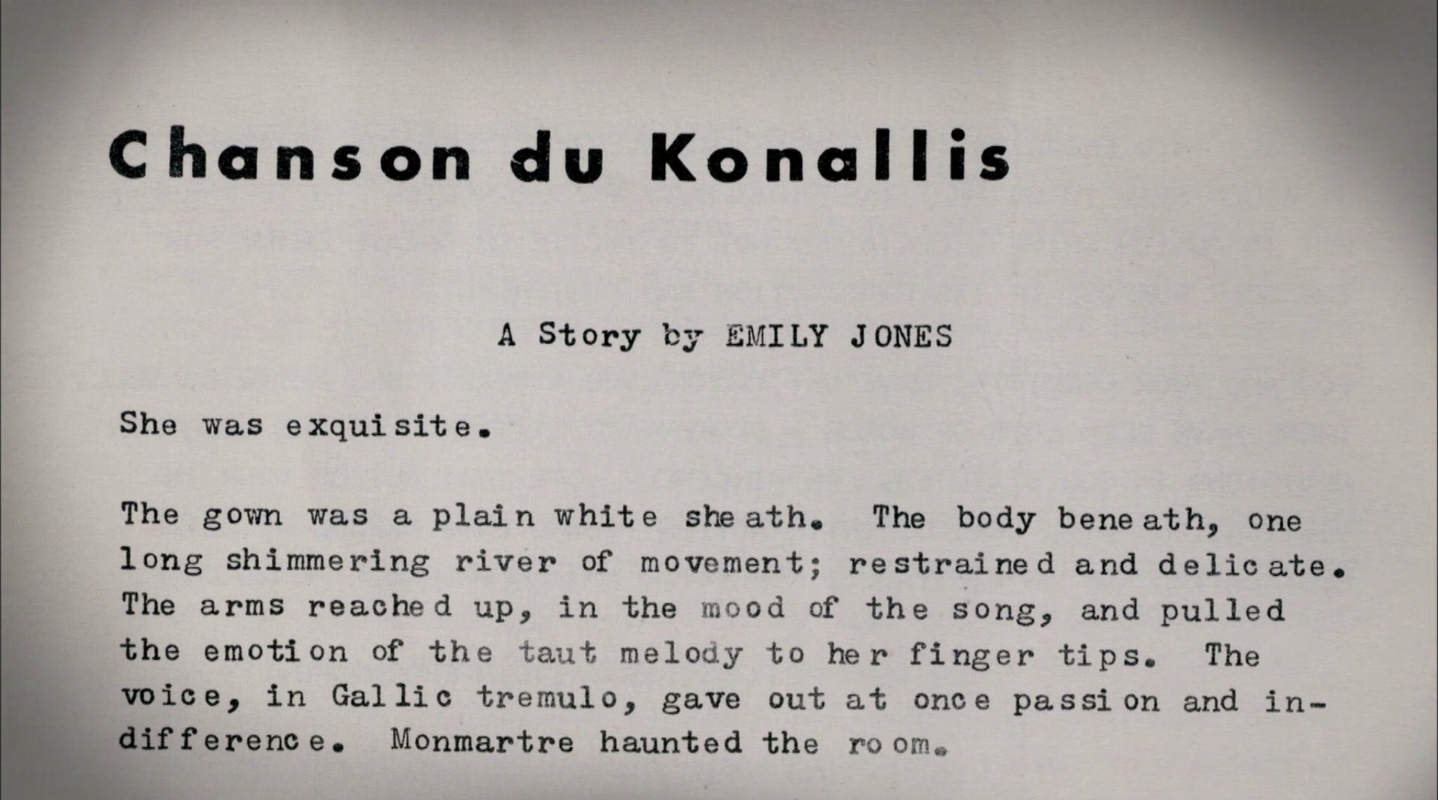

Using the pen name Emily Jones, she also wrote four lesbian-themed short stories: The Budget, The Anticipation of Eve, and Renascence, appearing in the major Los Angeles gay magazine ONE, and Chanson du Konallis, in a 1958 issue of The Ladder.

A few weeks before Raisin’s premiere, Hansberry went to her first of many lesbian house parties in Greenwich Village; one fellow guest, Renee Kaplan, with whom Hansberry had what was likely her first same-sex relationship, attended the premiere. She later dated writer Eve Ward (which was not her real name). Her lesbian social circle consisted of white women, including writers Marijane Meaker, Louise Fitzhugh, and Patricia Highsmith, and future LGBT rights activist Edie Windsor. While Hansberry was the only Black woman, and therefore isolated from other Black lesbian artists, her work would later inspire Audre Lorde, who wrote in her 1986 book, I Am Your Sister: Black Women Organizing Across Sexualities, “When you see the plays and read the words of Lorraine Hansberry, you are reading the words of a woman who loved women deeply.”

Hansberry bought and moved to the residential building at 112 Waverly Place in 1960.

Landmark Designations for LGBT Significance

In April 2021, through the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project’s extensive research and writing, the Lorraine Hansberry Residence was listed on the National Register of Historic Places by the U.S. Department of the Interior, following the site’s listing, in March 2021, on the New York State Register of Historic Places. The National Register report is available in the “Read More” section below.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (March 2018; last revised April 2021).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown

- Year Built: 1861

Sources

335-337 Bleecker Street, I-Card, New York City Housing Preservation & Development, April 30, 1958.

Elise Harris, “The Double Life of Lorraine Hansberry,” Out, September 1999, pp. 96-101, 174-175.

Imani Perry, Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018).

James Baldwin, “Sweet Lorraine,” (1969) in Lorraine Hansberry in Her Own Words: To Be Young, Gifted and Black, adapted by Robert Nemiroff (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), xviii.

Kevin Mumford, “Opening the Restricted Box: Lorraine Hansberry’s Lesbian Writing,” OutHistory, bit.ly/2pclVHA.

Melissa Anderson, “Lorraine Hansberry’s Letters Reveal the Playwright’s Private Struggle,” February 26, 2014, The Village Voice, bit.ly/2pc2QWb.

Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz, “Opening Remarks to Outing Lorraine at the Schomburg Center,” CUNY Academic Works, City University of New York, 2014.

Trish Bendix, “Lorraine Hansberry’s Secret Lesbian Herstory Touched Upon in New Documentary,” Into, January 18, 2018, bit.ly/2tNhvMl.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?