Justice for Julio March

overview

In 1990, Jackson Heights resident Julio Rivera was brutally attacked in the P.S. 69 schoolyard for being gay, and he soon after died at nearby Elmhurst Hospital.

A month later, a silent candlelight vigil called the Justice for Julio March ended outside the schoolyard, kicking off a series of public demonstrations that ultimately made Rivera’s murder the first gay hate crime to be tried in New York State.

History

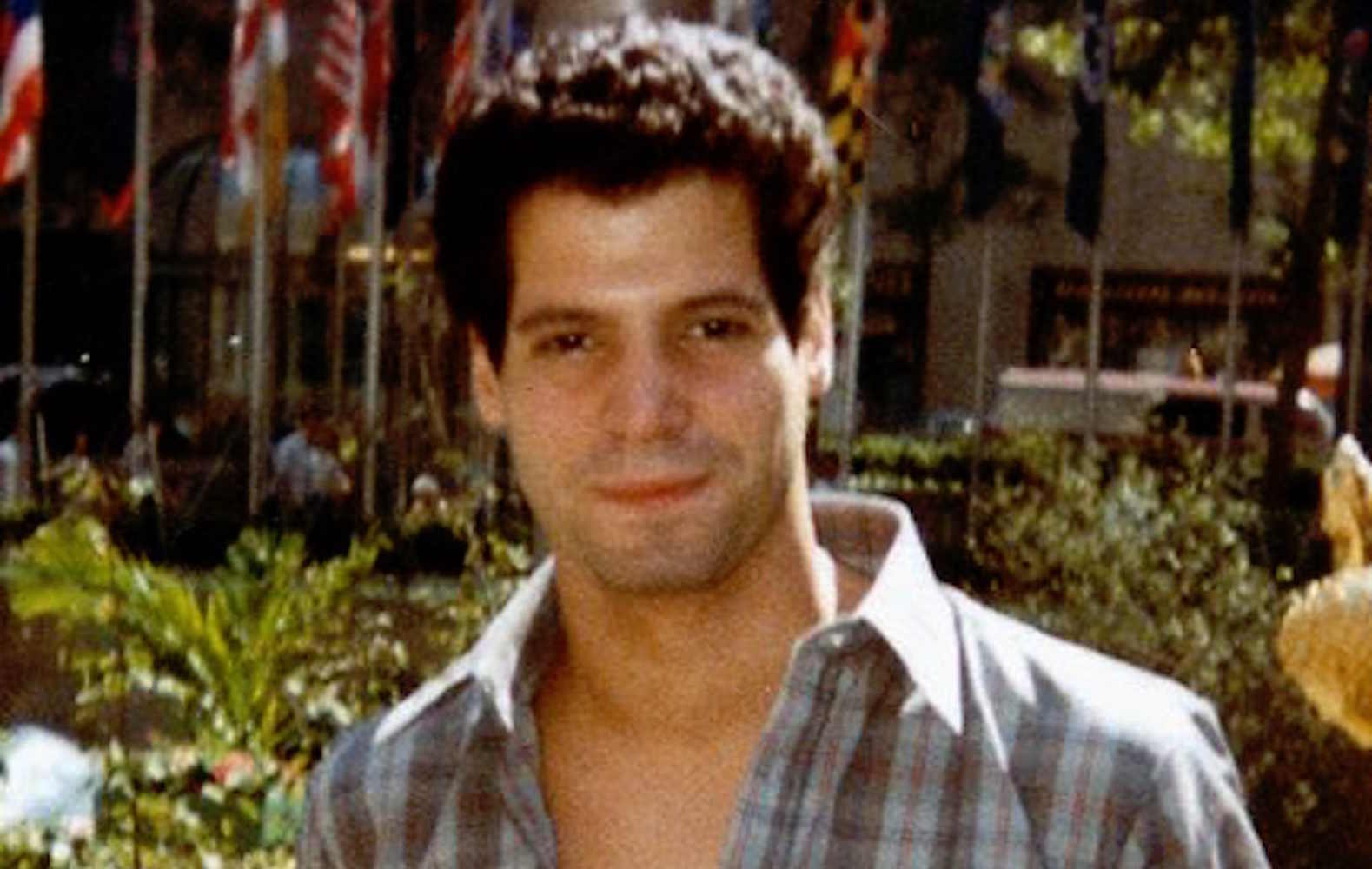

Julio Rivera (1961-1990), a 29-year-old Puerto Rican bartender raised in the Bronx, was living in Jackson Heights when, on July 2, 1990, three skinheads from a local street gang brutally attacked him in the schoolyard of P.S. 69, at the corner of 78th Street and 37th Avenue, because he was gay. He later died at Elmhurst Hospital.

Since the 1920s, Jackson Heights has been home to one of the largest LGBT communities in New York City, but at the time of the attack LGBT activism was largely non-existent in Queens. That changed beginning with Rivera’s murder, which Daniel Dromm called part of “Queens’s Stonewall.”

If it wasn’t for Julio the Queens LGBT movement would not have gotten as far as it has gotten. Julio did not die in vain. He changed people’s lives.

Tommy Grimaldi, owner of the Magic Touch, a popular Jackson Heights gay bar, and Alan Sack, Rivera’s friend and former lover – and one of the people to find him dying on the sidewalk – contacted the New York City Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project (now the NYC Anti-Violence Project; AVP) the morning after Rivera died. Working with AVP’s then-executive director Matt Foreman, Sack later attended a Queer Nation meeting at the LGBT Community Center in Manhattan and gave an impassioned plea for help in organizing a vigil. Ed Sedarbaum, a gay rights activist and social worker from Jackson Heights, became highly involved after attending this meeting.

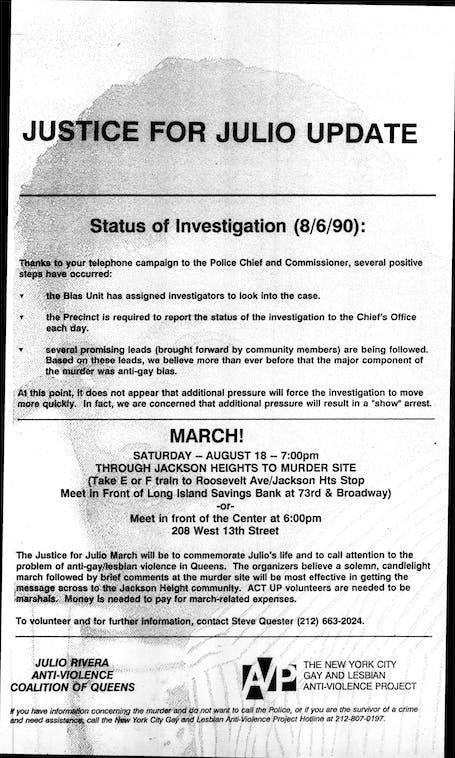

Planning for the vigil, which became the Justice for Julio March, largely took place in the basement of the Magic Touch. On August 18, 1990, at 7:00 p.m., six weeks after Rivera’s murder, his friends and family, members of the Latino (largely Puerto Rican) community, AVP, the Julio Rivera Anti-Violence Coalition of Queens, ACT UP, and Queer Nation, which brought hundreds of LGBT New Yorkers, participated in the silent candlelight vigil. Attendees met in front of the Long Island Savings Bank, at 73rd Street and Broadway, or the LGBT Community Center in Manhattan. The route moved through Jackson Heights, ending at the murder site.

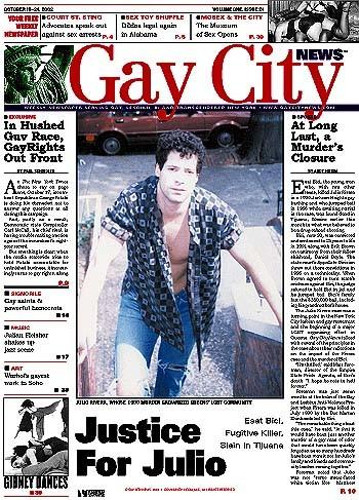

Considered the first gay public demonstration in Queens since a 1969 event in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the vigil was significant in expanding LGBT activism beyond Manhattan and connecting activists in both boroughs. It also marked the first time since 1969 that the gay community took a stand against homophobic hate crimes in Queens, which had included the deaths of at least six people and numerous gay bashings over several decades, and demanded that law enforcement finally address gay bias attacks (the police, for example, initially labeled Rivera’s murder as drug-related and assigned the case to an out-of-town detective). Additional advocacy efforts, such as two separate demonstrations in October 1990 to pressure Mayor David Dinkins into publicly acknowledging the murder, ultimately made Rivera’s case the first gay hate crime to be tried in New York State.

Reaction to his death also led to the formation of several important organizations, some of which include Queens Gays and Lesbians United (Q-GLU), the Lesbian and Gay Democratic Club of Queens, and Queens Pride House. Sedarbaum, co-founder of Q-GLU, worked with AVP to develop a training program for the 115th Police Precinct to help improve the relationship between the police and the LGBT community. Rivera’s sister-in-law, Peg Rivera, became a tireless advocate for LGBT issues and was the first ally elected to AVP’s board of directors. In 1993, the Queens Lesbian and Gay Pride Committee established the Queens Pride Parade. The route passes the site of Rivera’s murder, which is now marked by a street sign, Julio Rivera Corner, installed in 2000.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (March 2017; last revised December 2024).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Sources

Andy Humm, “Tears for Julio Rivera 25 Years After his Murder,” Gay City News, July 9, 2015. [source of pull quote]

Bill Parry, “Julio Rivera’s 1990 Murder to Be Remembered in Jackson Heights,” Gay City News, June 30, 2015.

David Gonzalez, “At Site of Gay Man’s Murder, a Street Corner Acknowledges Its Past,” The New York Times, March 20, 2016.

Eric Pooley, “With Extreme Prejudice: A Murder in Queens Exposes the Frightening Rise of Gay-Bashing,” New York Magazine, April 8, 1991, pp. 36-43.

Jeremiah Moss, “Julio of Jackson Heights,” Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York, March 18, 2011.

Joseph P. Fried, “2 Accomplices Guilty of Murder in ‘Gay Bashing’ Case in Queens,” The New York Times, November 21, 1991.

Luis Gallo, “Julio Rivera and the Making of a Hate Crime,” Latino USA, June 24, 2016.

Matt Foreman, e-mail to Ken Lustbander/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, September 10, 2018.

Richard Shpuntoff, Julio of Jackson Heights, documentary, 2016.

Richard Shpuntoff, phone call with Amanda Davis/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, July 17, 2018.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?