Howard Cruse & Ed Sedarbaum Residence

overview

Cartoonist Howard Cruse, credited as the “godfather of queer comics,” and leading community activist Ed Sedarbaum lived in this Jackson Heights apartment building from 1979 to 2002.

During this period, Cruse created influential works, including Gay Comix, Wendel, and Stuck Rubber Baby, and Sedarbaum focused on community building through efforts such as Queens Gays and Lesbians United (Q-GLU) and SAGE/Queens Clubhouse, a center for LGBT elders.

History

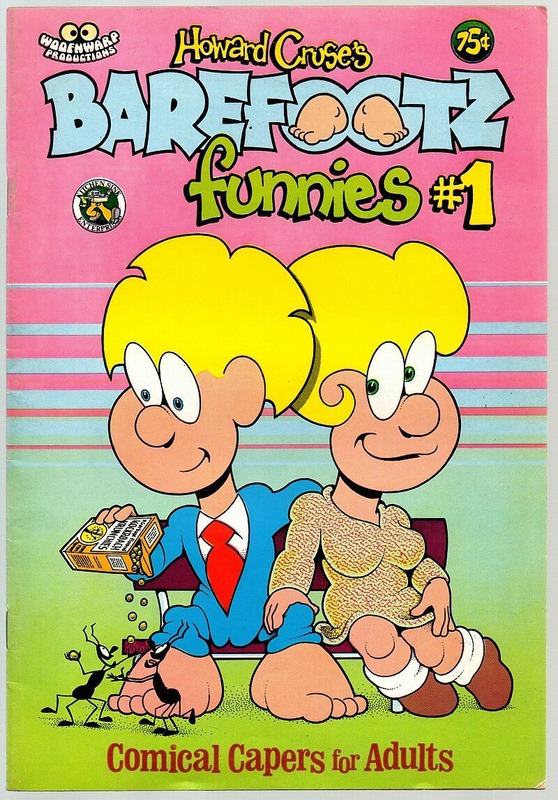

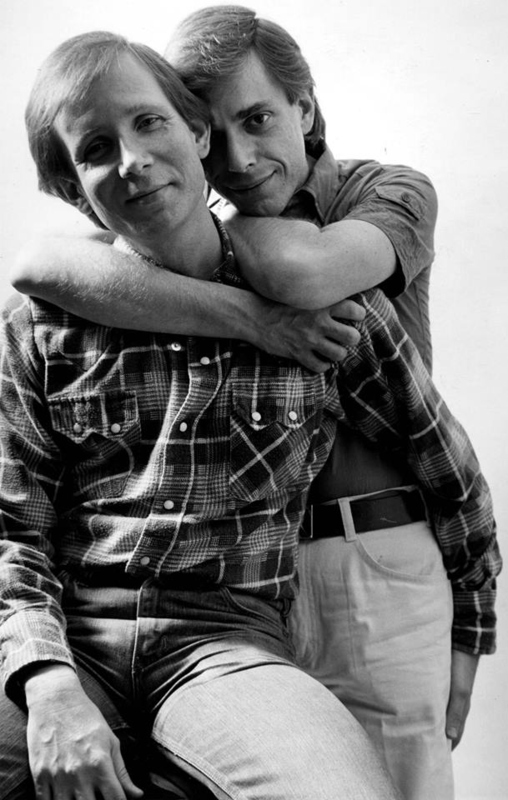

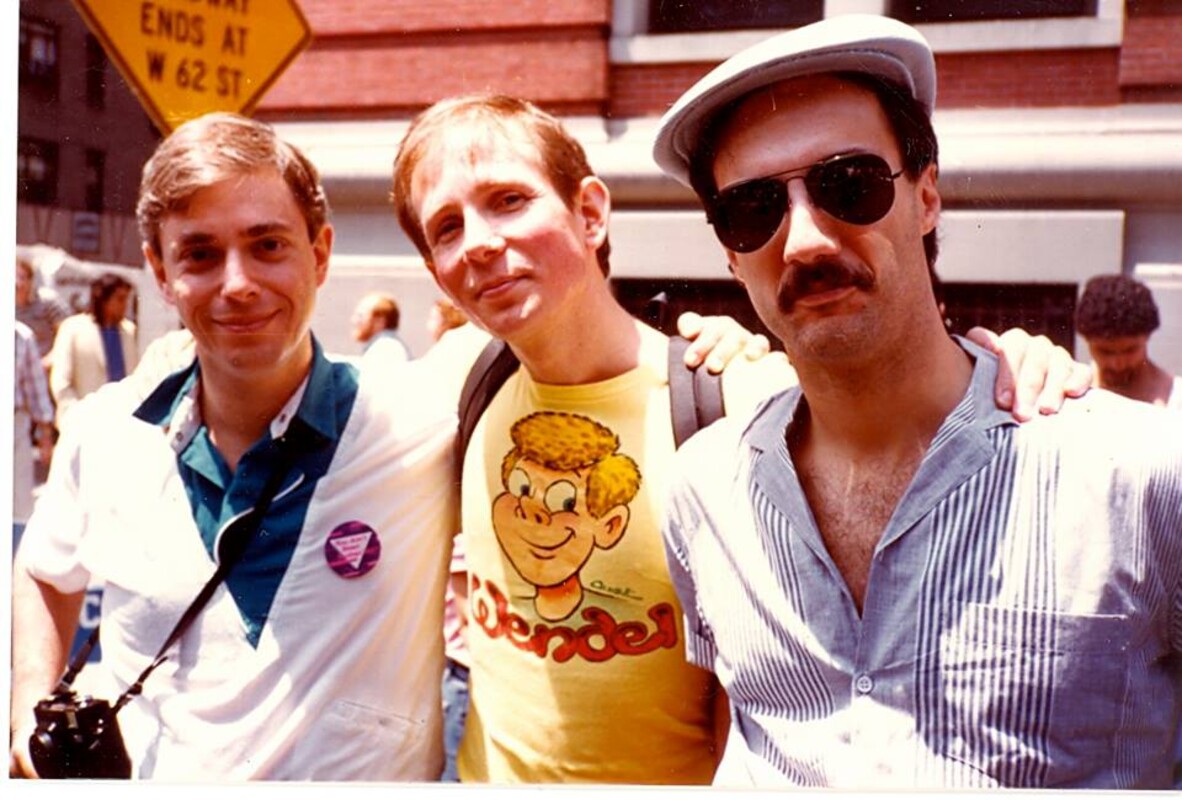

Howard Cruse (1944-2019) established himself as an underground cartoonist with the 1970s series Barefootz, which included a gay character that he eventually outed. He moved from Birmingham, Alabama, to New York City in 1976 and made a living as a freelance artist. In 1979, he met Ed Sedarbaum (1945-2024), who was then a caseworker at the NYC Department of Social Services. Sedarbaum, born in Brooklyn and raised in Queens, had recently left the Queens home he shared with his wife of ten years, who had known about his relationships with men. Seeking to help others who were also coming to terms with their sexuality, Sedarbaum began volunteering at the Gay Switchboard and led a rap session at Identity House, a walk-in counseling center in Manhattan.

Soon after they met, Cruse and Sedarbaum moved into an apartment at 88-11 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights, Queens, in 1979. Janine Utell, in her biography of Cruse, notes that he “would take up the apartment–floors, dining room table–with large-scale versions of his panels on Bristol board, working with undiluted focus once a story got going.” Sedarbaum, who became a freelance editor after leaving Social Services in 1981, edited Cruse’s work.

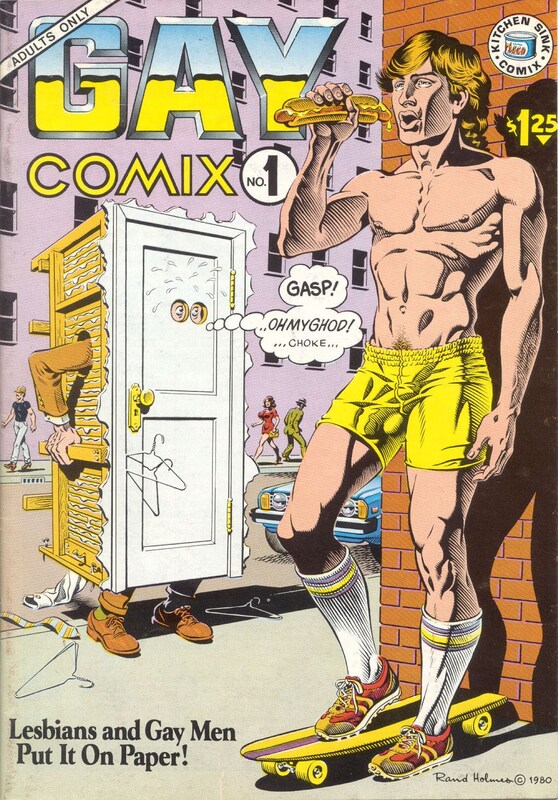

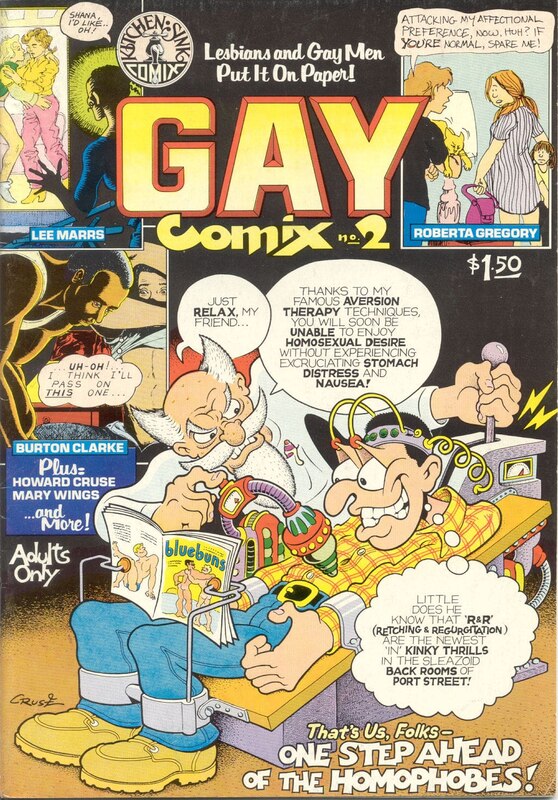

In 1980, Cruse was invited by publisher Denis Kitchen, who worked with him on Barefootz, to be the founding editor of a new series called Gay Comix. (The term “comix” refers to the underground comic book scene that arose following the Comics Code of 1954, which prohibited “controversial” topics.) Cruse, who was not yet out professionally, felt the series would provide much-needed visibility for LGBT people. He wrote a letter announcing the new publication to underground comix artists, straight and gay, which read, in part, “Many gay artists have never included the gay facets of their lifestyle in their published work, whether from fear of ostracism on a personal level, possible negative reactions from fans, or the chance that homophobia among editors or publishers could result in long-range career damage. As a gay artist myself, I have shared those fears.”

Utell writes that underground comix at the time was a straight man’s world where homophobia and misogyny were commonplace. Cruse, in developing Gay Comix as a three-dimensional portrayal of gay and lesbian experiences, drew inspiration from lesbian cartoonists who had pioneered the art form with lesbian-themed work in the early 1970s. Gay Comix was carried by several gay bookstores, including the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop. A young Alison Bechdel came across the first issue there in 1981, soon after moving to Manhattan, and credited it for shaping her career as an acclaimed cartoonist.

I had no career goals until I picked up [Gay Comix], and I knew at that moment what I was going to do with my life. [Howard Cruse] created a path for me and many other queer cartoonists.

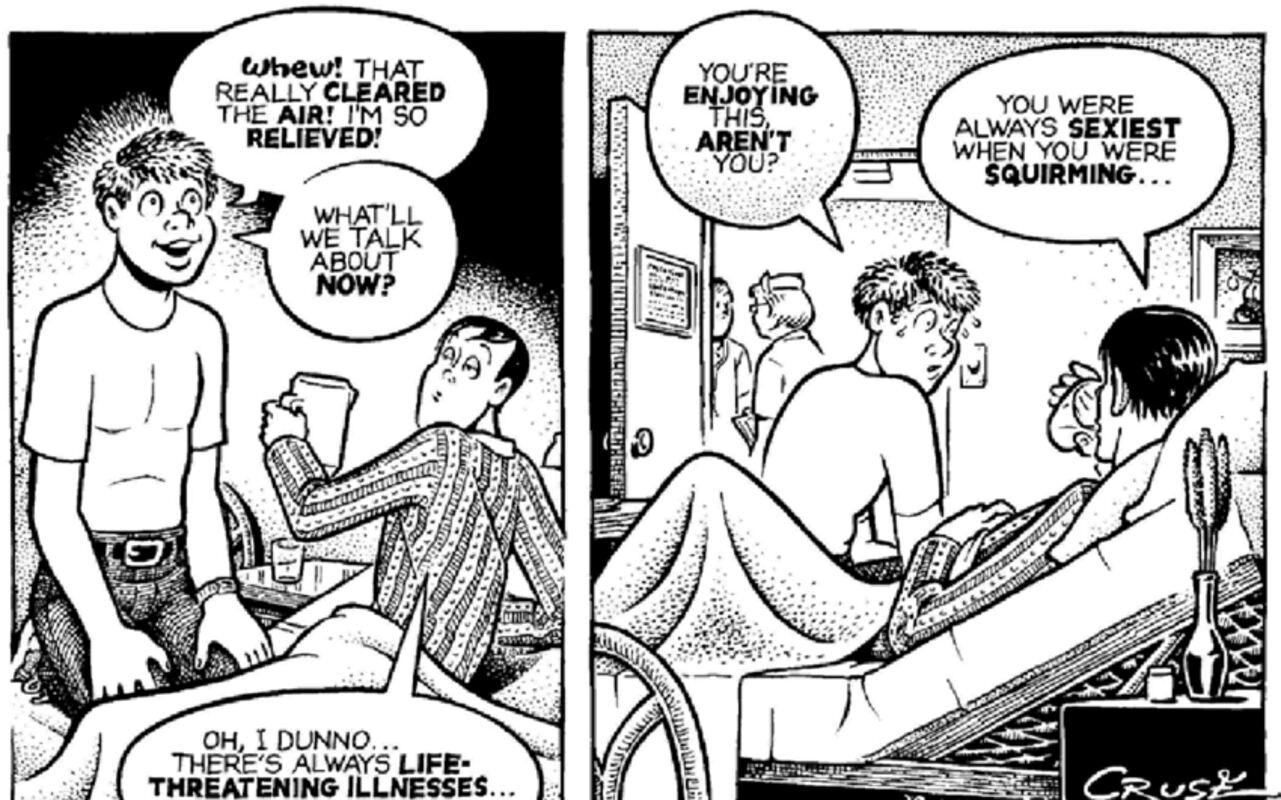

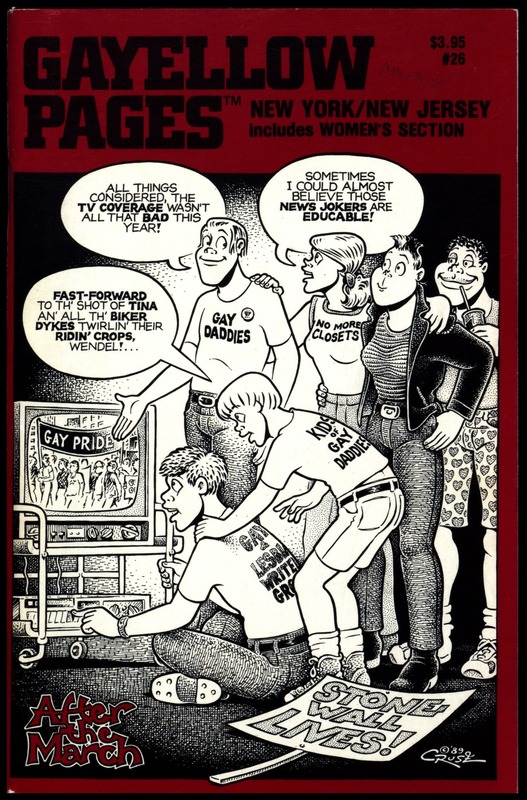

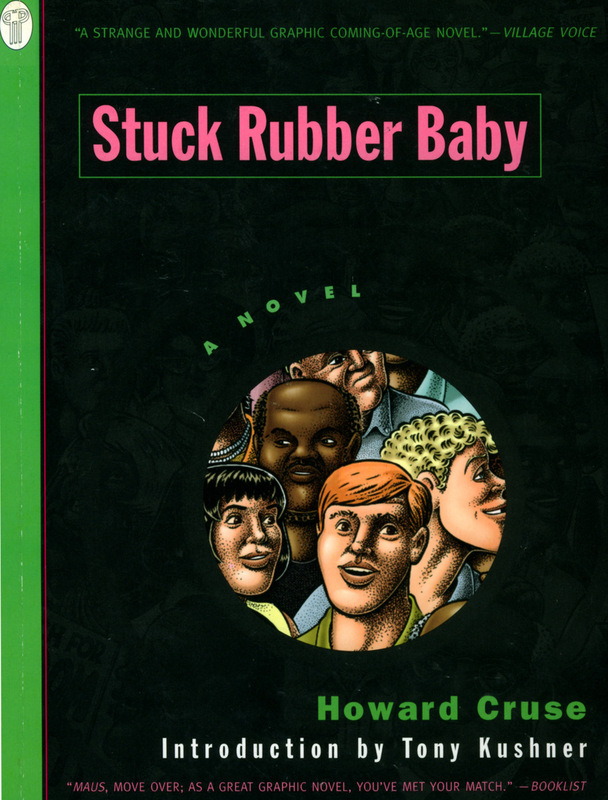

Cruse was the editor of Gay Comix for four issues before moving on to create Wendel, about a gay man and his lover during the early years of the AIDS epidemic, which appeared nationally in The Advocate from 1983 to 1989. His semi-autobiographical graphic novel, Stuck Rubber Baby (1995), received an Eisner Award and a Harvey Award, two of the highest honors in comics.

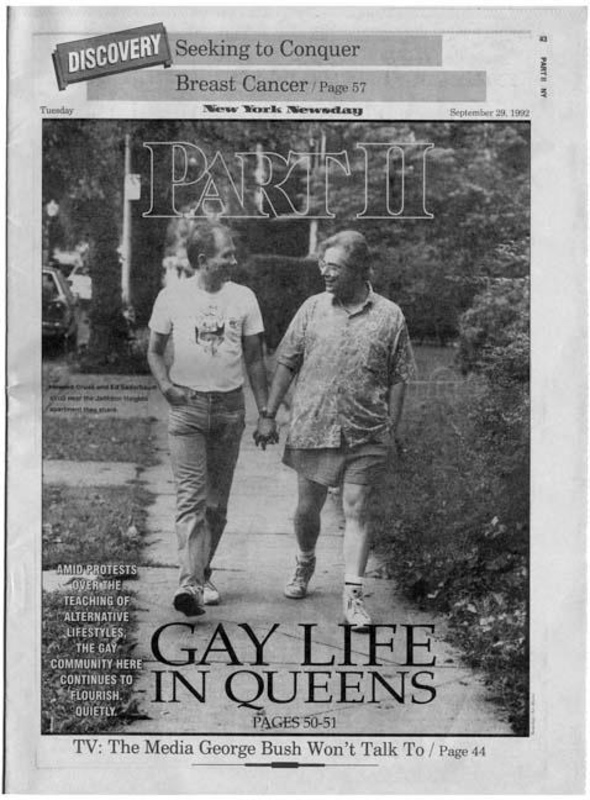

In the early 1990s, Cruse and Sedarbaum, whose gay social and activist life had been centered in Manhattan, became involved with the burgeoning LGBT rights movement in Queens following the murder of Julio Rivera. Sedarbaum, in particular, was a leading figure. In response to Rivera’s murder, and other gay hate crimes in the borough, Sedarbaum worked with the Anti-Violence Project (AVP) to develop a training program for the 115th Police Precinct to help improve the relationship between the police and the LGBT community. In 1991, he co-founded Queens Gays and Lesbians United (Q-GLU) with Susan Caust to address the needs of LGBT residents in their home borough. The first meeting was held at Cruse and Sedarbaum’s apartment; later meetings were held at the nearby Community United Methodist Church (Cruse provided artwork for various efforts, including those for Q-GLU and the Queens Pride Parade). Through Q-GLU, Sedarbaum also took part in the March for Truth, organized in 1993 to counter homophobic backlash to the NYC Department of Education’s “Children of the Rainbow” curriculum.

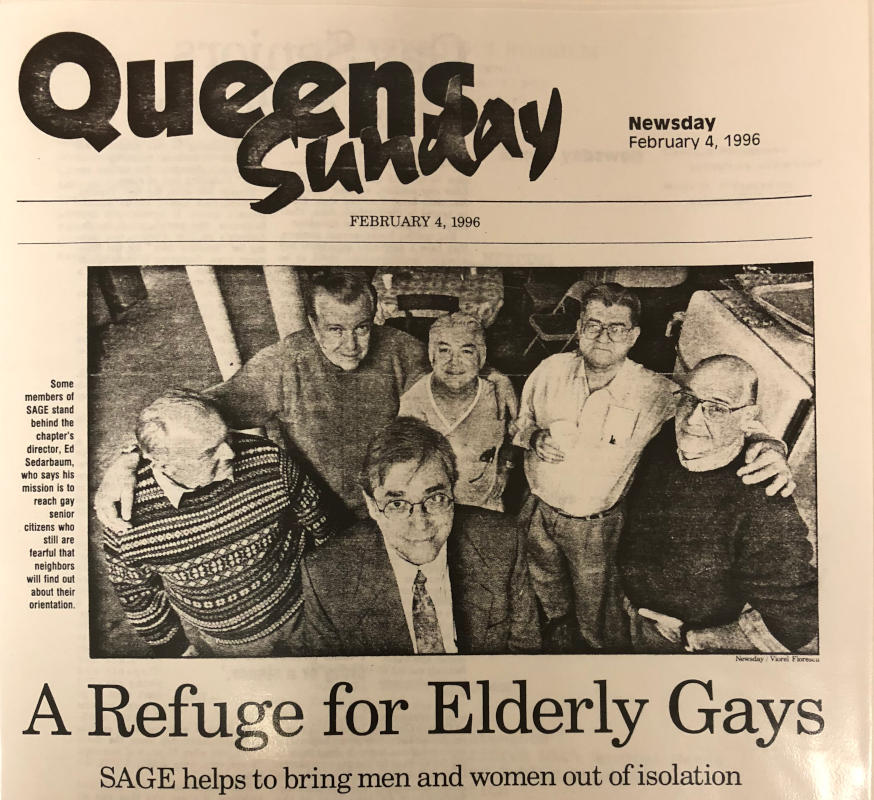

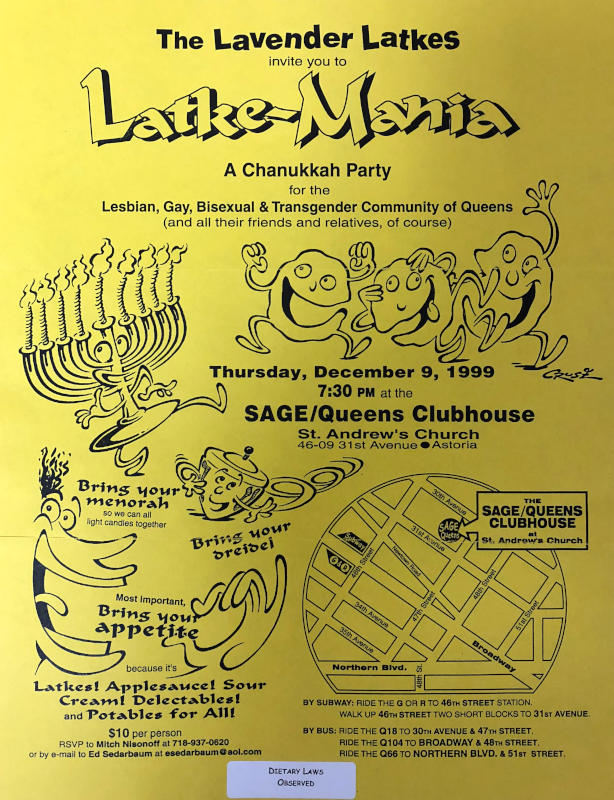

In 1995, Sedarbaum used his background as a former social worker to found SAGE/Queens Clubhouse, a center for LGBT elders that opened at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Astoria, Queens. He ran unsuccessfully in the 1998 race for the New York State Senate. That same year, he was the head of the Anti-Violence Project’s Hate Crimes Bill Coalition. Cruse and Sedarbaum left their Jackson Heights apartment in 2002 and settled in the Berkshires. They married in 2004 after same-sex marriage was legalized in Massachusetts.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (December 2023; last revised December 2024).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Philip Birnbaum

- Year Built: 1950

Sources

“A Three-Way Race,” The New York Times, August 30, 1998, CY8.

Alison Bechdel, “The Godfather of Queer Comics,” introduction to 25th anniversary edition of Howard Cruse’s Stuck Rubber Baby, published in Slate, July 21, 2020, bit.ly/41mXsAd.

Ed Sedarbaum, “Classes Improved Gays’ Ties to Police [letter to the editor, April 23, 1993],” The New York Times, May 4, 1993, A24.

Ed Sedarbaum, email to Amanda Davis/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, April 17, 2023.

Ed Sedarbaum, interview with Richard Shpuntoff, December 30, 2010.

Harrison Smith, “Howard Cruse, underground cartoonist and ‘godfather of queer comics,’ dies at 75,” The Washington Post, December 4, 2019, bit.ly/3QEa6WN.

Janine Utell, Howard Cruse (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2023).

Jeffrey Schmalz, “For Gay People, A Time of Triumph and Fear,” The New York Times, March 7, 1993, 37.

Norimitsu Onishi, “In a Gay Haven, a Sense of Community Builds,” The New York Times, December 4, 1994, CY9.

Richard Goldstein and Jay Blotcher, “Pioneering gay cartoonist Howard Cruse dies at 75,” LGBTQ Nation, December 2, 2019, bit.ly/3TxqI5J.

Richard Sandomir, “Howard Cruse Dies at 75; His Cartoons Explored Gay Life,” The New York Times, December 4, 2019, bit.ly/3Tf3Nvu. [source of pull quote]

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?