Hart Crane Residence

overview

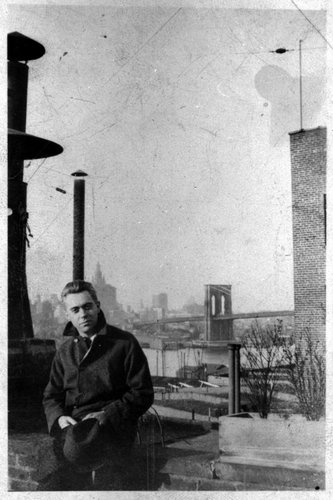

Posthumously considered an influential figure in modernist poetry, Hart Crane lived at 45 Grove Street during two separate stints in 1923 and 1924.

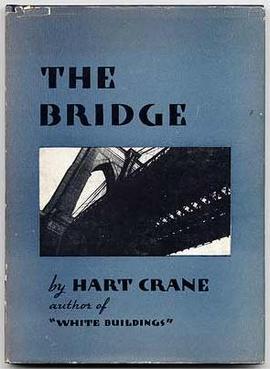

During this short but important period, he started on the first draft of his ambitious long poem, The Bridge, which is not only an epochal investigation of the American experience but also a mirror of the cultural and historical conditions of gay life.

History

Hart Crane (1899-1932), born in Garrettsville and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, moved to New York City at the age of 18 in 1917. Even though only a small portion of his life was spent in the city, it offered him a sanctuary as a poet, inspired his imagination, influenced his poetry, and, as his biographer Clive Fisher has noted, “introduced him to the idea of metropolitan literary culture.”

The city is ablaze with life … the avenues sparkle and money seems to just roll in the gutters. I am looking on it all with different, keener eyes than ever before.

In his early years in the city, from January 1917 to November 1919, Crane was struggling financially while working in advertising for several publications. He worked at the Little Review and lived above its office at 24 West 16th Street. In January 1923, during a trip back to Cleveland, Crane conceived the idea of The Bridge (1930), which would become his most ambitious work. He described it as “a mystical synthesis of ‘America.’”

From June to November 1923 and January to February 1924, Crane lived at 45 Grove Street, which he considered to be a writing sanctuary. Another tenant in the building at this time was the drama critic Stark Young. While living here, Crane continued working on The Bridge and discussed the project in letters to his mother and close friends. At 45 Grove Street, Crane finished an early draft of “Atlantis,” which would become the final section of The Bridge. From contemporaneous correspondence it appears that this was among the happiest periods in his life. In his large, second-floor room, he wrote:

…I am all fixed up in my own room and as happy as a bug in a rug! … I have a fine large table to write on. When my luck turned it seemed to turn equally favorably in every direction.

In the summer of 1923, when living at 45 Grove Street, Crane also composed short poems about his personal life cruising for sex. He channeled his worries and gratification into obscure verses that he later summarized as “the imponderable phenomena of psychic motives.” Possessions, from September 1923, has a metaphorical narrative with subtle homosexual undertones:

Accumulate such moments to an hour:

Account the total of this trembling tabulation.

I know the screen, the distant flying taps

And stabbing medley that sways —

Rounding behind to press and grind,

And the mercy, feminine, that stays

As though prepared.

Crane moved often throughout his short life, including elsewhere in the Village: 6 Minetta Lane, the Hotel Albert at 23 East 10th Street, and 15 Van Nest Place (now 15 Charles Street). In April 1924, Crane moved to 110 Columbia Heights (demolished) in Brooklyn, which was the house of his lover Emil Opffer’s father. From a window there, Crane could see the Brooklyn Bridge, the subject of The Bridge. By this time, he finished Voyages (1923), a poem dedicated to Opffer, and the first draft of The Bridge, which was published in 1930. After this time, Crane’s residences in the city included 77 Willow Street, 130 Columbia Heights (demolished), and 190 Columbia Heights, all in Brooklyn.

In the last years of his life, Crane went into a personal, economic, and creative decline. As a result, in 1932, during his travels in Mexico on a Guggenheim Fellowship, Crane committed suicide by jumping into the Gulf of Mexico at the age of 33.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Crane was considered a failed Romantic poet. However, his work was rediscovered by academics of modernist poetry in the 1960s as well as queer theorists, such as Tim Dean, in the 1980s. As a result, Crane is now considered an exceptional poet who reflected the cultural and historical conditions of queer life in his work. In Hart Crane’s Queer Modernist Aesthetic (2015), author Niall Munro notes, “Hart Crane created an alternative form of literary modernism, queering modernist experience. It goes beyond representations of sexuality in the texts to show how Crane employs queerness as an intellectual strategy in order to engage with and interrogate a number of modernist concerns.”

Entry by Hongye Wang, project consultant (August 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown; Benjamin G. Wells (addition)

- Year Built: 1830; 1871 (combined with neighboring building and given two-story addition)

Sources

Brom Weber, ed., The Letters of Hart Crane, 1916-1932 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1965).

Clive Fisher, Hart Crane: A Life (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002). [source of Fisher quote]

“Hart Crane Papers: 1909-1937,” Archival Materials, Box 13-17, Butler Library, Columbia University.

“Hart Crane,” Poetry Foundation, May 7, 2019, bit.ly/3BImaAs.

Lawrence Kramer, ed., Hart Crane’s The Bridge: An Annotated Edition (New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 2011).

Niall Munro, Hart Crane’s Queer Modernist Aesthetic (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). [source of Munro quote]

Warner Berthoff, Hart Crane, A Re-Introduction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?