Frances Perkins Residence

overview

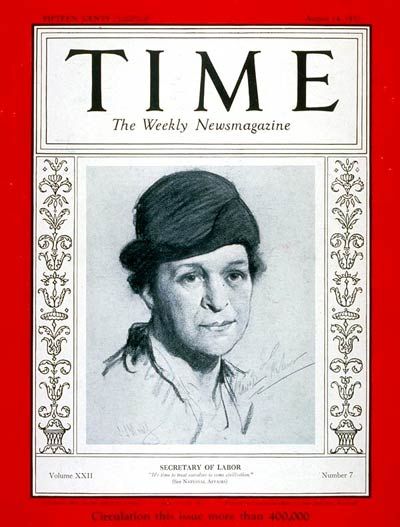

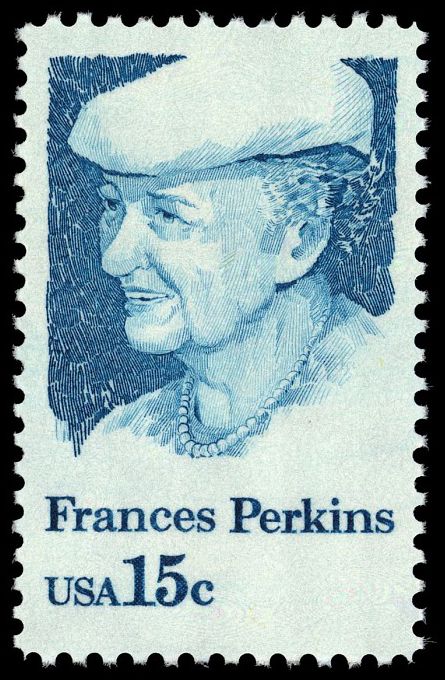

Labor reform advocate Frances Perkins was a trusted adviser to Franklin D. Roosevelt, serving as Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor throughout his gubernatorial and presidential administrations.

The first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet, Perkins lived in this Greenwich Village apartment building in the early 1910s.

History

On the afternoon of March 25, 1911, Frances Perkins (1880-1965), the director of the New York Consumers League, was having tea with a friend on Washington Square North when they heard a tremendous commotion on the street. Perkins went to investigate and watched as workers at the Triangle Waist Company jumped from the eighth and ninth floors of their burning factory. In total, 146 people, mostly young, Eastern European Jewish and Italian immigrant women, died in this notorious fire. Perkins was stunned by the horror of the event and, according to her biographer Kirsten Downey:

It is without doubt that the Triangle fire was a turning point. It reoriented her life.

Perkins was born in Boston to a family with early roots in Maine (the family homestead in Newcastle, Maine, which Perkins was attached to, is now a National Historic Landmark). She studied science at Mt. Holyoke College and then moved to Chicago for a teaching job where she also volunteered at Jane Addams’ Hull House, confirming her interests in settlement work, labor reform, and suffrage. In 1909, Perkins enrolled in a graduate program at Columbia, receiving a Master’s in Sociology and Economics. She briefly lived at Hartley House and at Greenwich House, two New York settlements, before moving into a small apartment at 164 Waverly Place in Greenwich Village in about 1910. After graduation, Perkins became Executive Secretary of the Consumers League, an organization that fought for labor reform. Shortly after the Triangle fire she attended the memorial held at Carnegie Hall where she responded to the call to action demanded by Rose Schneiderman in her fiery speech at the event.

Perkins left the Consumers League and, at the recommendation of Theodore Roosevelt, became the executive secretary to the Committee on Safety of the City of New York, where, in 1913, she successfully lobbied for a bill in the state legislature capping work weekly hours of women and children at 54. In this role, she also worked behind the scenes with the Factory Investigating Commission to assure the passage of a package of reform laws in response to the Triangle fire. In that year she also married Paul Caldwell Wilson, but kept her maiden name for her professional work. After their marriage, Perkins and Wilson moved to 121 Washington Place in 1913. Soon after, Wilson began to show signs of mental illness and spent much of the rest of his life in and out of institutions.

In 1919, Governor Al Smith appointed Perkins to the Industrial Commission of the State of New York. She was the first woman to hold an administrative position in New York State’s government. A decade later, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her the New York State Industrial Commissioner, where she advocated for a 48-hour work week for women and for unemployment insurance. With FDR’s election as president, Perkins became Secretary of Labor — the first woman cabinet member in U.S. history. She retained this position throughout the Roosevelt administration and was responsible for the development of Social Security, the funding of public works projects such as post offices and schools, and the Fair Labor Standards Act, and has been called “the Architect of the Civilian Conservation Corps.” In 1944, Collier’s magazine enthused that it was “not so much the Roosevelt New Deal, as … the Perkins New Deal.”

In 1933, on arriving in Washington, D.C., Perkins moved into the townhouse of Mary Hartman Rumsey, a wealthy friend from New York who, like Perkins, was a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt and a Democratic Party activist, as well as a social leader in the capital. Rumsey had been involved in settlement work and was the founder of the Junior League, originally the Junior League for the Promotion of the Settlement House Movement. FDR appointed her to chair the Consumer Advisory Board, a new government consumer rights group. Perkins and Rumsey had a close and loving relationship, entertaining as a couple and spending weekends at their houses on Long Island and in Virginia. But, as Kirsten Downing notes “it is probably impossible to know whether Frances’s relationship with Mary was also sexual or romantic.” Shortly after Rumsey died in 1934, Perkins moved into the Washington home of New York congresswoman Caroline O’Day.

Following FDR’s death, President Truman appointed Perkins to the U.S. Civil Service Commission and in 1955 she became a lecturer at Cornell University’s new School of Industrial Relations.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (July 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Bernstein & Bernstein

- Year Built: 1907

Sources

“Frances Perkins,” National Park Service, bit.ly/3De45JY.

“Frances Perkins: From Greenwich House to the White House,” Village Preservation, November 20, 2019, bit.ly/3OgHX80.

Frances Perkins Center, bit.ly/3pUytpJ.

“Frances Perkins, the First Woman in Cabinet, Is Dead,” The New York Times, May 15, 1965, 1.

Kirsten Downey, The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR’s Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2009). [source of pull quote, p. 36, and “Frances’s relationship” quote, 166]

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?