Félix González-Torres Residence & Studio

overview

Artist Félix González-Torres was known for his conceptual, minimalist art installations that employed everyday objects to reflect on his experiences as an openly gay Cuban-American wrestling with both the personal and communal impacts of AIDS, discriminatory public policies, and censorship of LGBT artists.

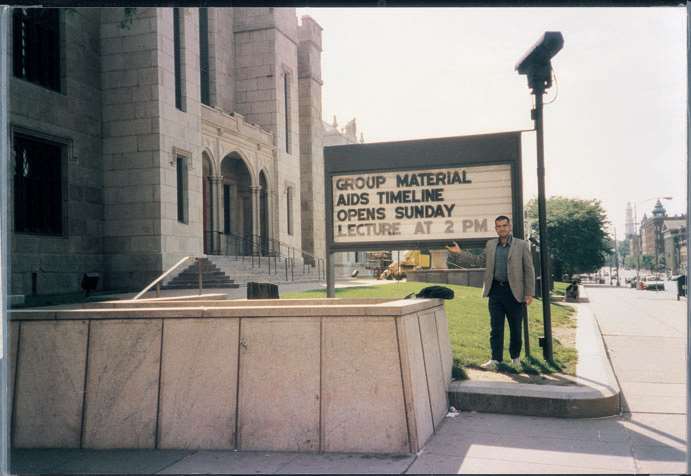

While living in this small studio apartment, from 1985 to 1990, González-Torres became a member of the art-activism collective Group Material, began teaching at NYU, had his first solo exhibitions, and initiated experiments with new mediums.

History

Félix González-Torres (1957-1996) was born in Guáimaro, Cuba, amidst the Cuban Revolution. He moved to New York in 1979 to study photography at Pratt Institute and participate in the Whitney Independent Study Program, in 1981 and 1983.

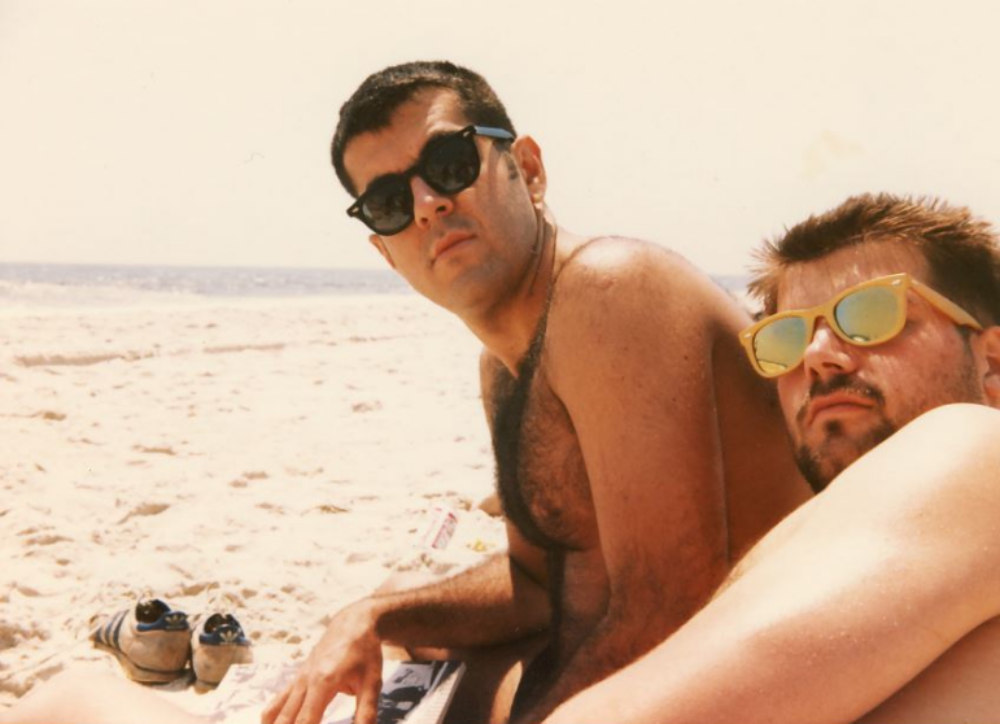

Also in 1983, González-Torres met Canadian Ross Laycock (1959-1991) at Boy Bar on St. Mark’s Place, Manhattan. A “Renaissance man,” as described by González-Torres, Laycock was an aspiring menswear designer who moved to New York in 1980 to attend FIT but returned to Canada shortly after meeting González-Torres to study Biochemistry and English, while also becoming a local AIDS activist and sommelier. Despite their geographic separation and disparate careers, González-Torres and Laycock quickly became “intertwined on a molecular level, like all great love relationships. Inseparable, yet unique,” in the words of their close friend, artist Carl George.

When visiting one another, they stayed in Laycock’s kitsch-filled Toronto home, which they christened “Pee-Wee Herman’s Playhouse Part 2,” or in González-Torres’s small studio at 19-21 Grove Street. He began renting the first floor’s leftmost unit, 1B, in 1985 and later said of his time here, “I’ve never been so happy in my whole life.” Here, while completing master’s degrees at NYU and the International Center of Photography in 1987, González-Torres created his earliest works, experimenting with mediums he would later be known for using, including dateline photostats, billboards, stack pieces, and jigsaw puzzles. Later that year, he joined the art-activism collective Group Material and began teaching at NYU, but his art’s emphasis shifted sharply to Laycock after his AIDS diagnosis in 1988.

Laycock’s declining health inspired González-Torres’ most poignant works, which subtly addressed AIDS and homosexuality but also invoked universal themes of love, loss, hope, and mortality. His subtlety and decision to label pieces “Untitled” with only a parenthetical hinting at his interpretation was a refusal to “give the powers that be what they want, what they are expecting from [gay artists]”: explicitly “gay” art that could easily be sensationalized, politicized, and censored.

Gonzalez-Torres eschews the role of Latin artist or queer artist or even activist artist, while making use of everything his experience as a politically committed gay man has taught him.

This subversion averted censorship and enabled his work, as his posthumous Foundation says was his intention, to “always be present and open to new understandings and contexts” rather than being “circumscribed by the time frame and context in which [he] lived.”

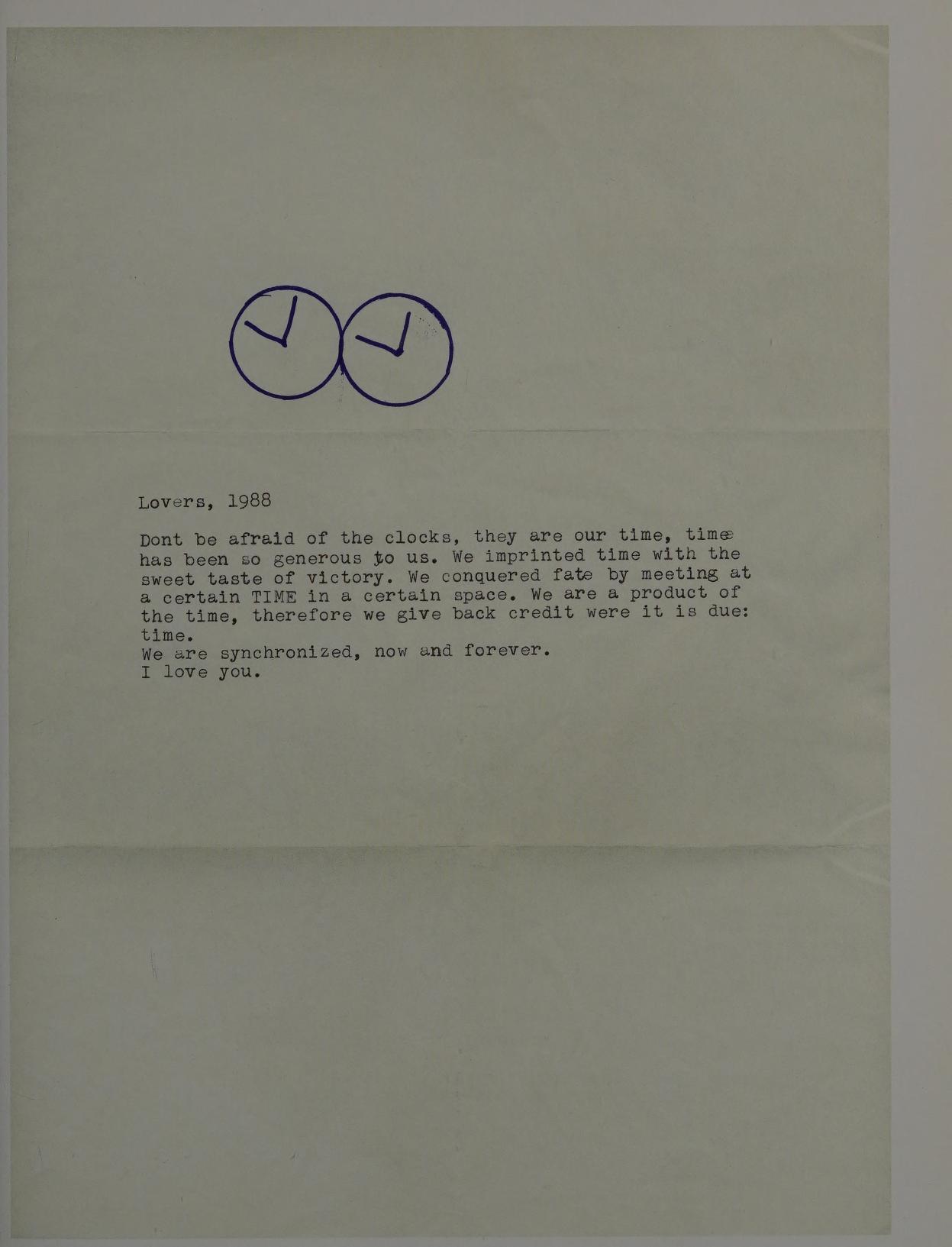

In “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers), a seminal piece conceptualized in 1987, two identical, commercially-available clocks are synchronized and hung with their edges gently touching. As one clock’s batteries would inevitably die first, allegorical for Laycock’s impending death, González-Torres instructed their replacement and resynchronization, effectively immortalizing his undying love for Laycock. The piece also revealed the effectiveness of his subtlety when a conservative US Senator, expecting obscenity, threatened to close González-Torres’ 1994 exhibition but ultimately left with unmet expectations. Unperturbed, González-Torres suspected that it would remind the senator of his wife, and, therefore, “his own ability to be moved by two clocks side by side, ticking together, will mean that my love is equal to his love.”

After leaving Grove Street in 1990 to teach in California, González-Torres created “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in LA), a candy spill whose ideal weight equals Laycock’s healthy body weight. Inviting viewers to consume the candy, the sculpture’s gradual diminishment would parallel that of Laycock and, as art educator Matthew Isherwood observes, “remind viewers of their complicity” in the AIDS epidemic.

In a way this ‘letting go’ of the work, this refusal to make a static form, a monolithic sculpture, in favor of a disappearing, changing, unstable, and fragile form was an attempt on my part to rehearse my fears of having Ross disappear day by day right in front of my eyes.

On January 24, 1991, these fears were realized when Laycock died in Toronto. Upon returning to New York, González-Torres moved to 215 West 10th Street, Apt. 5D, and created “Untitled,” a photographic billboard of his empty bed. The impressions of two bodies evoke absence and grief, but González-Torres’s decision to thrust the bed, generally considered private, into a public context also asserts, as MoMA curator Anne Umland analyzes, that the bed “stands as a legislated and socially contested zone” for LGBT individuals.

By 1993, Gonzalez-Torres lived in London Terrace, 420 West 24th Street, Apt. 16B, splitting his later years between there and Miami, where he succumbed to AIDS in 1996 after a prolific decade of art-making that made strides in his “desire to make this place a better place.”

Entry by Ethan Brown, project consultant (August 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Bruno W. Berger

- Year Built: 1891

Sources

Alex Fialho, “Finding Aid,” Carl George/Felix Gonzalez-Torres/Ross Laycock Archive (New York: Visual AIDS Archive Project, 2018).

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, interview by Robert Storr, “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Être un espion / Being a Spy,” Art Press (January 1995), 24-32.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, interview by Ross Bleckner, “Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” BOMB Magazine, April 1, 1995 (accessed July 18, 2022), bit.ly/3NJ8gAe.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, interview by Tim Rollins, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (New York: A.R.T. Press, 1993). [source of second pull quote]

Shawn Diamond, “Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Ross Laycock & Carl George: An archive of love and loss at Visual AIDS,” The Visual AIDS Blog (accessed July 18, 2022), bit.ly/3RUuwul.

Matthew Isherwood, “Toward a Queer Aesthetic Sensibility: Orientation, Disposition, and Desire,” Studies in Art Education (Autumn 2020), 230-239.

M.H. Miller, “A Colossal New Show Revisits a Conceptual Art Icon,” The New York Times, May 11, 2017 (accessed July 18, 2022), nyti.ms/3aYPHL6.

Robert Storr, “Setting Traps for the Mind and Heart,” Art in America (January 1996), 71-77. [source of first pull quote]

Read More

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?