overview

Opened in 1950, Bo Bo Restaurant was the first and most well-known of numerous New York City restaurants established by Esther Eng, an openly lesbian Chinese American former film director and actress.

Bo Bo was named after Eng’s friend who was stranded in New York with his theatrical troupe, and the restaurant became a haven for out-of-work Chinese actors.

History

Before becoming a restaurateur, Esther Eng (1914-1970), born Ng Kam-ha in San Francisco, was a pioneering figure in the United States and Hong Kong film industries, beginning in the 1930s. Eng was Hong Kong’s first female film director and the first Chinese American female director to make a film in Hollywood. Her ten films, produced from 1935 to 1949, were groundbreaking for the time, with Cantonese opera performers starring as strong female leads in genres ranging from action to romance.

According to S. Louisa Wei, Eng’s filmmaking career began in Hollywood in 1935 as co-producer of Heartaches, the first all-Chinese sound motion picture entirely produced in the United States, before her relocation to Hong Kong in 1936. Eng was openly lesbian throughout her career in Hong Kong, and was often rumored to be in relationships with her leading ladies who Chinese columnists referred to as Eng’s “bosom friends” and “good sisters.” Her sexuality was not known to have affected her career negatively; as S. Louisa Wei noted in her research on Eng, in 1938 the Hong Kong newspaper Sing Tao Daily remarked that she was “living proof of the possibility of same-sex love.” This was due in part to the fact that many early film actors came from the Chinese opera world where all-female troupes featuring male-impersonating actresses were commonplace and homosexuality was accepted. Eng’s masculine gender presentation was not out of the ordinary, and she was respectfully known as “Brother Ha” or “Ha Go” after her Cantonese name and due to her short, slicked back hair and typical clothing choices of suits and collared shirts. Eng returned to California in 1939 and directed and released Golden Gate Girl in 1941 before a hiatus during World War II. In 1946, Eng resumed her filmmaking career in Hollywood, and produced two color films before she quit filmmaking in order to take over her father’s film distribution business in 1949.

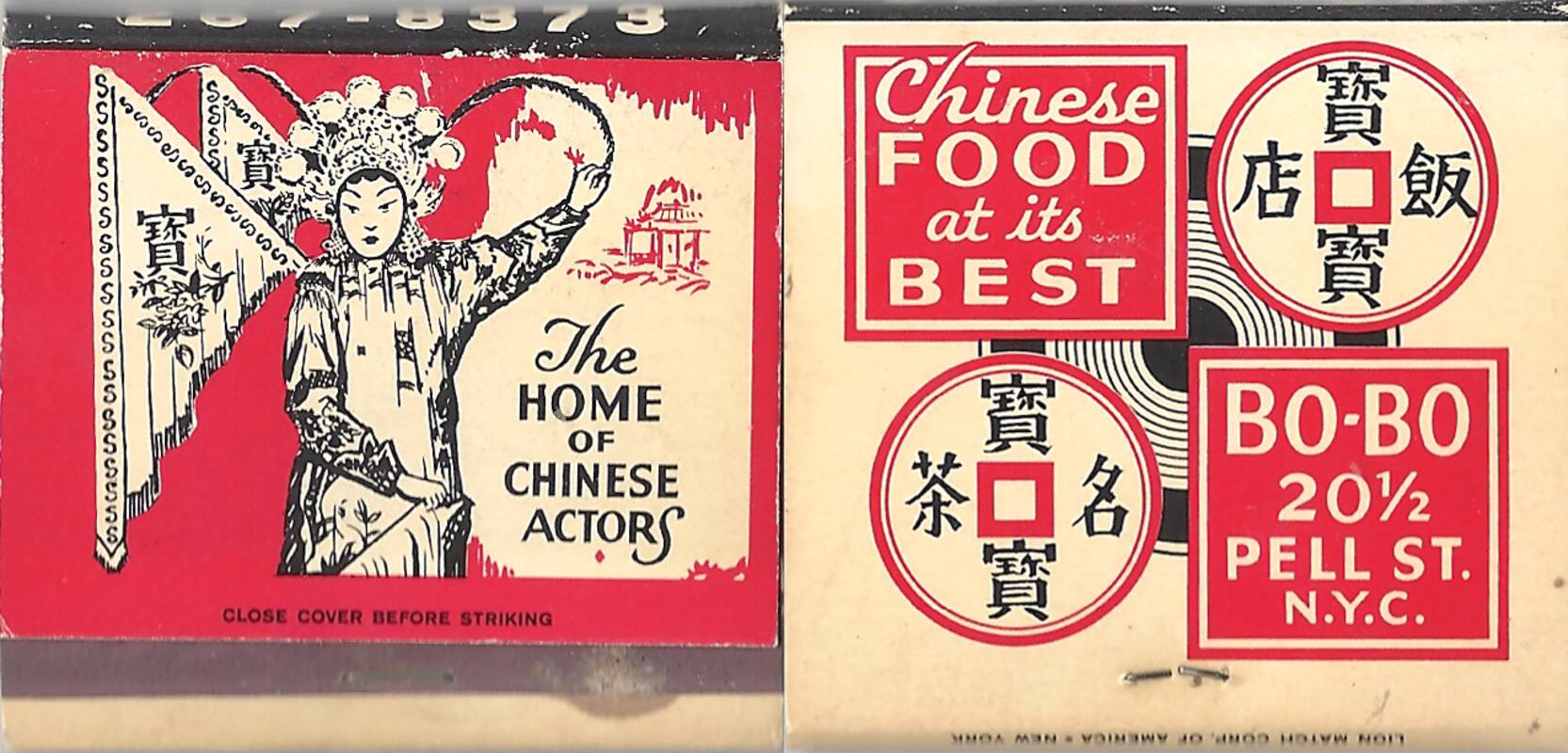

Eng’s next venture was as a New York restaurateur. After moving from San Francisco in 1950, Eng met an old friend, Bo Bo (a common Chinese nickname meaning “baby” or “darling”), who, along with his non-English speaking theater troupe, was unable to return to China after the Communist victory the year prior. Eng opened her first restaurant, Bo Bo, at 20½ Pell Street in Chinatown, to provide work to the troupe, and over time the restaurant became a refuge for out-of-work Chinese theater and film actors. Bo Bo’s matchbooks depicted a Cantonese opera singer with the tagline “the home of Chinese actors,” a reminder of the restaurant’s theatrical roots and staff makeup. According to Bruce Edward Hall’s 1998 memoir, Eng was an outspoken lesbian during her career as a restaurateur. Hall wrote she maintained her masculine dress and haircuts, and her ex-girlfriends often managed her restaurants. Eng also continued to distribute Hong Kong films and ran a theater that showcased Cantonese film and Cantonese opera.

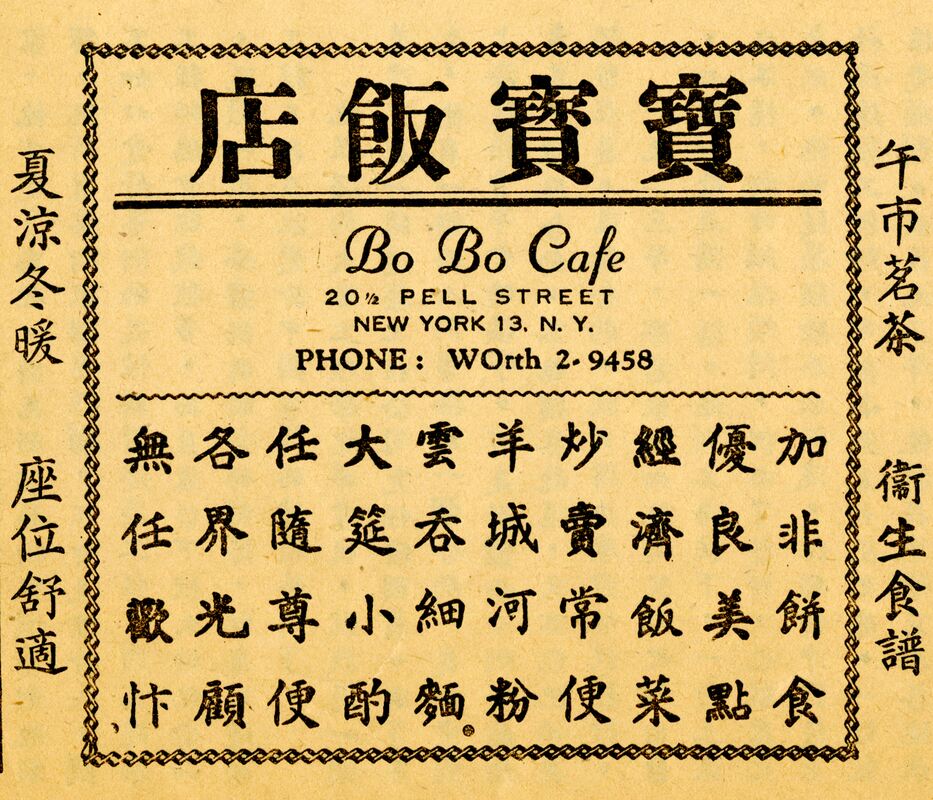

Bo Bo was well known for its food, with customer favorites including lobster egg rolls and duck with lychee. Chinese language ads promoted more downhome Cantonese dishes such as rice noodles and wontons at economical prices. The restaurant was also highly regarded in New York’s restaurant world. In 1964, it received a two-star rating from longtime New York Times critic Craig Claiborne, who remarked that the restaurant’s food was “made with a fine Chinese hand”. Claiborne noted that the only issue with Bo Bo was its extreme popularity, but that the long wait for a table was well worth it. Eng eventually sold her stake in the restaurant once the staff spoke enough English to run the establishment themselves.

Shortly after selling Bo Bo in 1959, Eng opened her second restaurant, the eponymous Esther Eng at East 57th Street and Second Avenue. While its food was not as well reviewed, the short-lived restaurant became a gathering spot for celebrities such as Tennessee Williams, Marlon Brando, and Italian actress Anna Magnani. Eng eventually closed the restaurant due to poor business.

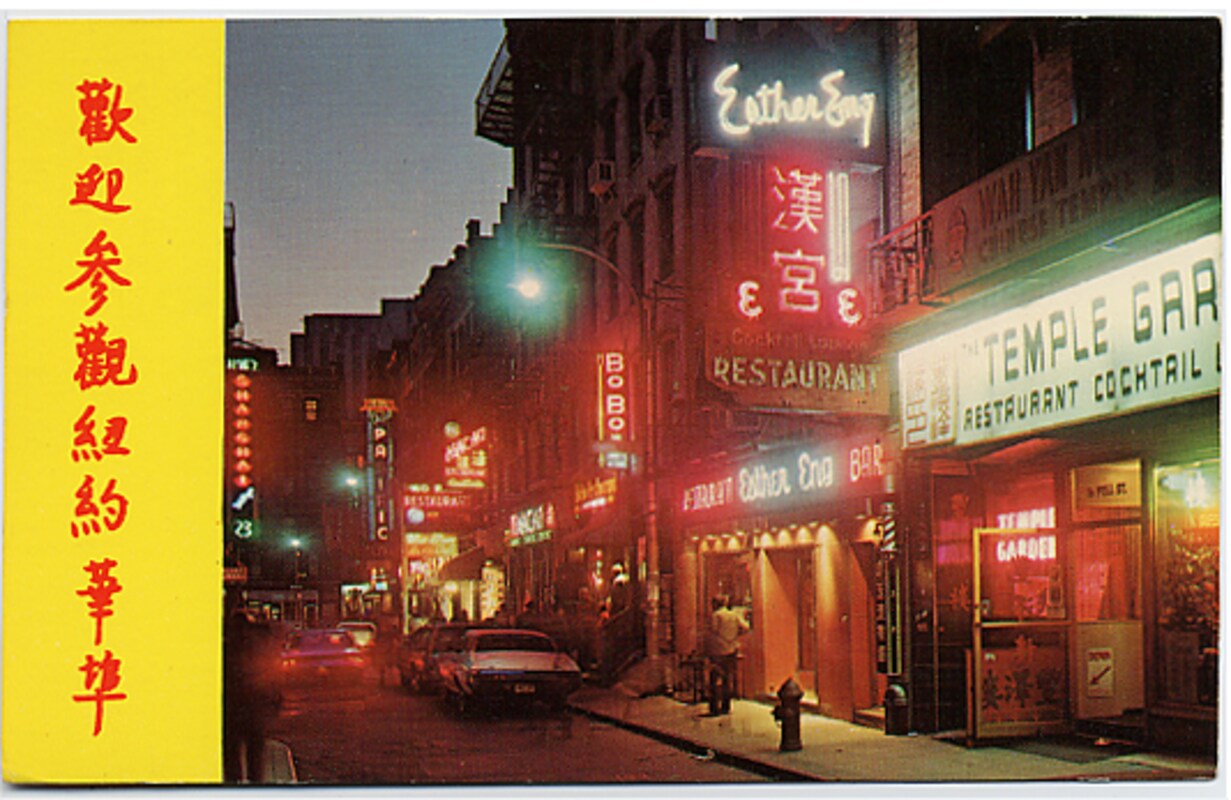

After closing her uptown restaurant, Eng opened a number of restaurants near Bo Bo – Macao at 22 Pell Street, Eng’s Corner at 1 Mott Street, and a relocated Esther Eng (named Han Palace in Chinese) at 18 Pell Street. She also opened Hing Hing (named after the woman who managed it) at 100 Second Avenue in the East Village. Eng’s new restaurants were a rousing success with diners, with her newly located self-titled restaurant being the most notable. Eng, who lived at 50 Bayard Street in Chinatown at the end of her life, continued to operate her restaurants until her early death from cancer at 55 in 1970.

Entry by Conrad E. Grimmer, project consultant (August 2024).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown

- Year Built: 1910

Sources

“Bo Bo in 1950: Where Chinese Actors Served Chow Gai Kew,” New York Magazine, 2024.

Bruce Edward Hall, The Tea That Burns: A Family Memoir of Chinatown, 1998.

Christiane A. Gadd, “Esther Eng (1914-1970): Filmmaker, Restaurateur, Gender Rebel,” OutHistory, 2016.

Chitralekha Basu, “Gay forever,” China Daily, October 24, 2010.

Craig Claiborne, “Food: Oriental Fare: Another Chinese Restaurant Opens – Menu Lists Cellophane-Wrapped Fowl,” The New York Times, June 19, 1959.

Craig Claiborne, ed., The New York Times Guide to Dining Out in New York, 1964.

Craig Claiborne, “Utensils and Edibles for Oriental Dishes Are in Abundance,” The New York Times, October 23, 1958.

Derek Elley, “Golden Gate Silver Light,” Film Business Asia, June 4, 2013.

“Esther ENG (1914-1970),” Hong Kong Film Archive, 2023.

“Esther Eng, Owned Restaurants Here,” The New York Times, January 27, 1970.

Frank Bren, “Electric phantom – the indomitable Esther Eng,” China Daily, January 23, 2010.

Frank Bren, “Esther Eng – Electric Shadow,” in Transcending Space and Time—Early Cinematic Experience of Hong Kong Vol.3, 2014, 36-69.

Kathleen McLaughlin, “Clothes and Food Spur Chinatown Economy,” The New York Times, June 29, 1967.

Lisa Cam, “Why haven’t we heard of early LGBTQ+ icon Esther Eng, Hollywood’s first Chinese female filmmaker?,” South China Morning Post, January 29, 2020.

“Restaurants Pace 2d Av. Growth,” New York Herald Tribune, May 3, 1959.

S. Louisa Wei, “Esther Eng,” Women Film Pioneers Project, 2014.

Tim Gray, “Pioneering Filmmaker Esther Eng Made Movies in the ’30s and ’40s on Her Own Terms,” Variety, June 21, 2019.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?