Cole Porter Residence at the Waldorf Towers

the apartment hotel, with its own entrance on East 50th Street, located on the upper floors of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel

overview

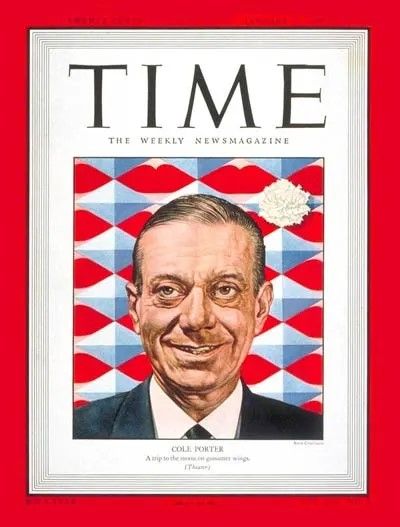

Cole Porter, one of the great songwriters of the 1930s and 1940s and a key figure in the American Songbook, moved into the Waldorf Towers in 1935 and lived here, in two different apartments, until his death in 1964.

Although he never wrote overtly homoerotic songs, Porter’s complex lyrics have often been given gay interpretations and his songs remain among the most popular ever written.

History

The work of songwriter Cole Porter (1891-1964) evokes an era of romantic glamor both on Broadway and in Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. He was the composer and lyricist for many staples of the American Songbook, including such classic songs as “Let’s Do It, Let’s Fall in Love” (1928; Porter’s first big hit), “Love for Sale” (1930), “Night and Day” (1932), “Easy to Love” (1934), “You’re the Tops” (1934), “Anything Goes” (1934), “I Get a Kick Out of You” (1934), “Begin the Beguine” (1935), “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” (1936), “My Heart Belongs to Daddy” (1938), “Another Opening Another Show” (1948), and “I Love Paris” (1953).

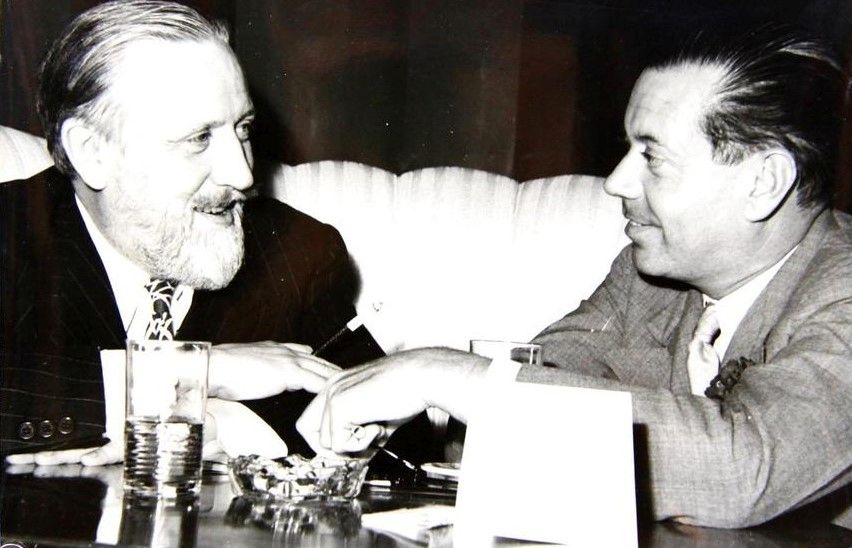

Porter was born into a wealthy family in Peru, Indiana. He attended Yale where he wrote songs for student productions and football games, including the ever popular “Bingo” and “Eli Yale.” While at Yale he met his lifelong friend, actor and director Monty Woolley, best known for playing Sheridan Whiteside in the play and movie The Man Who Came to Dinner. After college, Porter spent much of his time in Paris and Venice or traveling in Europe with a new set of wealthy, often titled, friends.

In 1918, he met the well-heeled and glamorous Linda Thomas in Paris and they soon married. Thomas had been in an abusive relationship and was happy with her sexless marriage with Porter. She accepted his homosexuality so long as it was not public and they developed a close and affectionate relationship. According to Ray Kelly, a friend and sometime lover of Cole’s, “until she was sold on the song, Porter keeps working at it.”

According to biographer Charles Schwartz, Porter favored “tall and burly truck-driver and sailor types,” including both white and Black men. Porter and Woolley were known to have frequented the “buffet flat” in Harlem of Clinton Moore at 304 West 147th Street, where Porter paid for sex (as he often did, according to Schwartz, using a number of other pimps to find available men). However, he did have several important romantic relationships over the years, first with Boris Kochno, the régisseur for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe (and once Diaghilev’s lover), then in the 1930s with architect Ed Tauch (a friend of Porter’s said that Tauch was “the great love of Cole Porter’s life”), and later with director John Wilson, dancer and choreographer Nelson Barclift, and actor Robert Bray.

After writing forgettable songs for several Broadway reviews and shows as early as 1915, Porter decided to take songwriting seriously. Beginning with Paris in 1928 and Fifty Million Frenchmen in 1929, he wrote the music and lyrics for a series of successful Depression-era Broadway shows, most notably The New Yorkers (1930), Gay Divorce (1932), and, especially, Anything Goes (1935). In early 1935, Variety enthused:

This is the Cole Porter year. Almost every platter, chatter and radio gives out something by Porter.

Porter generally waited for the book for a show to be written and then wrote songs that fit with the story. He wrote many sexually suggestive and highly erotic lyrics. Since it was not possible to write songs that were overtly homoerotic, given the era, his songs have coded language with subtle references to gay love that would have been recognized by gay audiences at the time of their premieres. Various sources suggest that “Easy to Love,” “In the Still of the Night,” and “Night and Day” were written for Tauch and “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To” for Barclift.

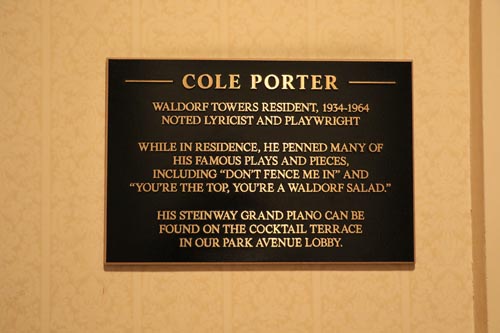

In 1935, Porter moved into a suite on the 41st floor of the Waldorf Towers, the apartment hotel that occupied the upper floors of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Park Avenue and had its own entrance on 50th Street. His close friend Elsa Maxwell already lived in this luxurious building. He furnished his suite in a lavish manner, including two grand pianos, placed back-to-back, one of which was a gift from the hotel and will be on view in the lobby when the Waldorf reopens in 2025. Thomas had a separate apartment across the hall. In 1954, following Thomas’s death, Porter moved into a larger apartment on the 33rd floor that was a major work by interior designer Billy Baldwin and was published in Vogue. Porter wrote many of his most famous songs in these apartments.

In 1935, Porter started spending time in Hollywood writing songs for movies. In Hollywood, he embraced his homosexuality far more than in New York and his Sunday, all-male pool parties came to rival those of director George Cukor for popularity and notoriety. This more open gay life created an estrangement with Thomas. She is said to have been seeking a divorce at the time Porter suffered a catastrophic accident – a horse threw him and rolled over on his legs crushing them and leading to multiple operations and excruciating pain for the rest of his life. Thomas returned to care for him.

Porter’s Broadway shows of the 1930s had flimsy plots held together by his witty and romantic songs. After World War II, book musicals, with the songs growing out of the plot and characterizations, transformed the Broadway musical. Porter rose to the challenge of creating this new type of musical with his masterpiece, Kiss Me Kate (1948), which won Tony Awards for Best Musical and Best Composer and Lyricist, followed by Can-Can (1953) and Silk Stockings (1955).

Porter’s biographer, William McBrien sums up Porter’s career and his sexuality:

[Porter] expressed his passions in his songs. He had to exercise great restraint because in his lifetime the audience would have repudiated love songs written by a known homosexual.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (July 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

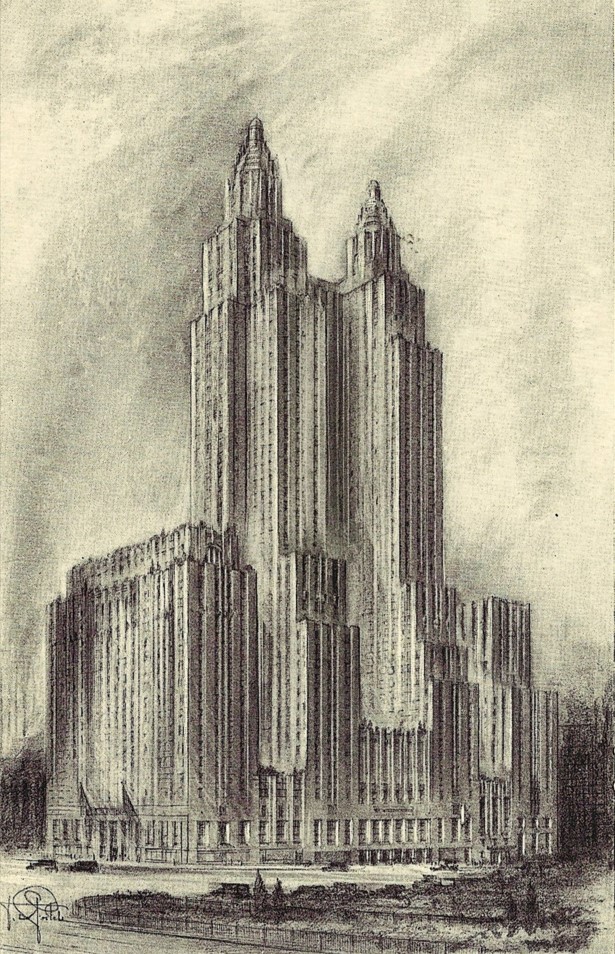

- Architect or Builder: Schultze & Weaver

- Year Built: 1929-31

Sources

Adam Gopnik, “From Minor to Major: The Pleasure and Pain of Being Cole Porter,” The New Yorker, 95 (January 20, 2020): 69-73.

Charles Schwartz, Cole Porter: A Biography (New York: The Dial Press, 1977).

“Cole Porter’s Apartment: Country House on the 33rd Floor,” Vogue 126 (November 1, 1955): 130-133.

David Grafton, Red, Hot & Rich: An Oral History of Cole Porter (New York: Stein and Day, 1987).

Elisa Rolle, Days of Love: Celebrating LGBT History One Story at a Time (CreateSpace, 2014).

Mark Fearnow, “Let’s Do It: The Layered Life of Cole Porter,” in Kim Marra and Robert A. Schanke, eds, Staging Desire: Queer Readings of American Theater History (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001), pp. 145-166.

William McBrien, Cole Porter: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?