overview

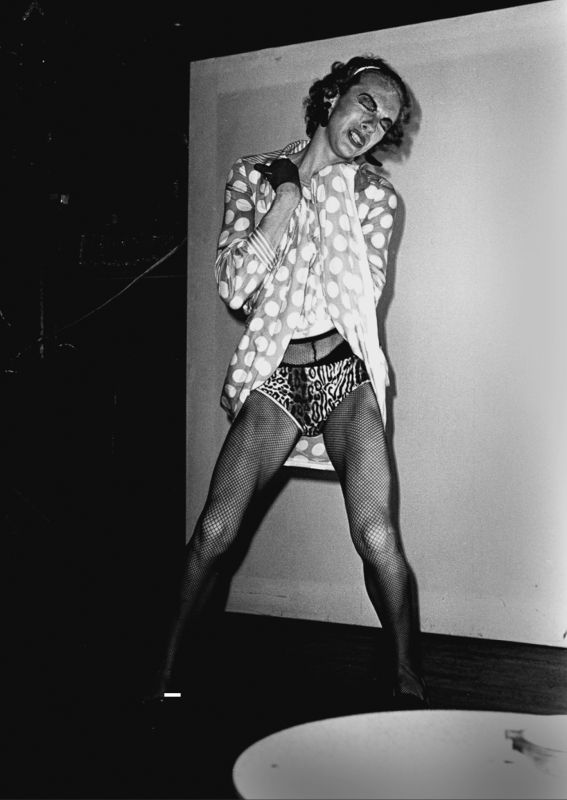

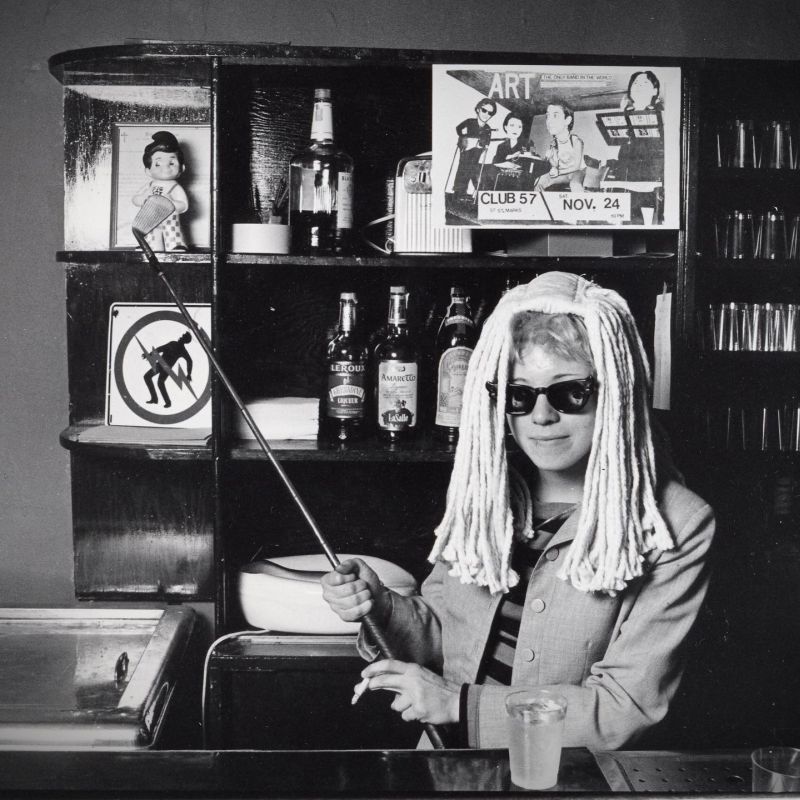

In operation from 1978 to 1983, Club 57 was a nightclub and performance space as well as an influential cultural incubator for the burgeoning downtown avant-garde art scene during that period.

Located in the empty basement of the Holy Cross Polish National Catholic Church, Club 57 was known for its punk, homemade/do-it-yourself aesthetic, and became a regular hangout and venue for countless visual artists and performers, many of whom were LGBT.

History

In 1978, bishops from the Holy Cross Polish National Catholic Church at 57 St. Mark’s Place tasked Stanley Strychacki, a Polish immigrant known in the neighborhood for organizing social and cultural events, with finding a use for the church’s empty basement as a way to raise additional revenue for the institution. Strychacki ultimately called the space Club 57 and began booking punk and garage bands like the Fleshtones and Misfits. However, the noise level and complexity of organizing rock concerts led him to look for other kinds of events. By November of that year, he invited Susan Hannaford and Tom Scully, the organizers of a series of “New Wave Vaudeville” revues at Irving Plaza, where Strychacki was also the manager, to take over Club 57.

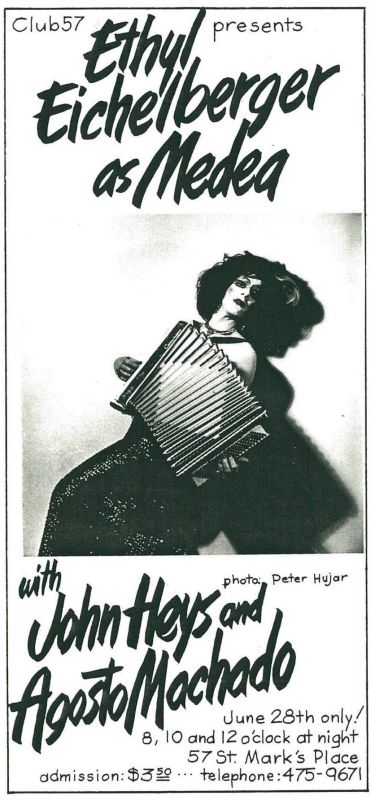

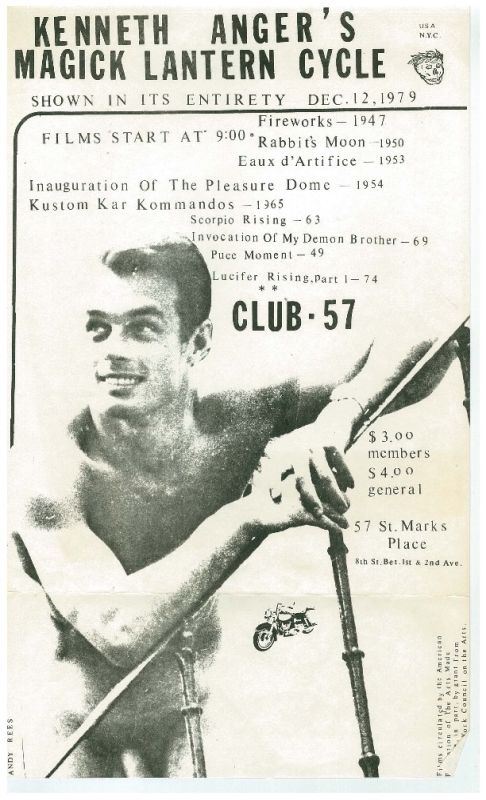

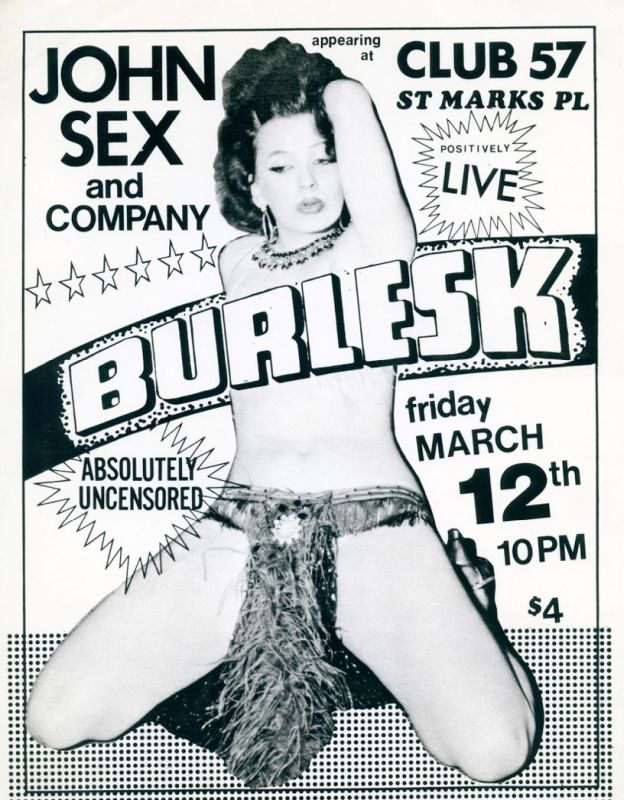

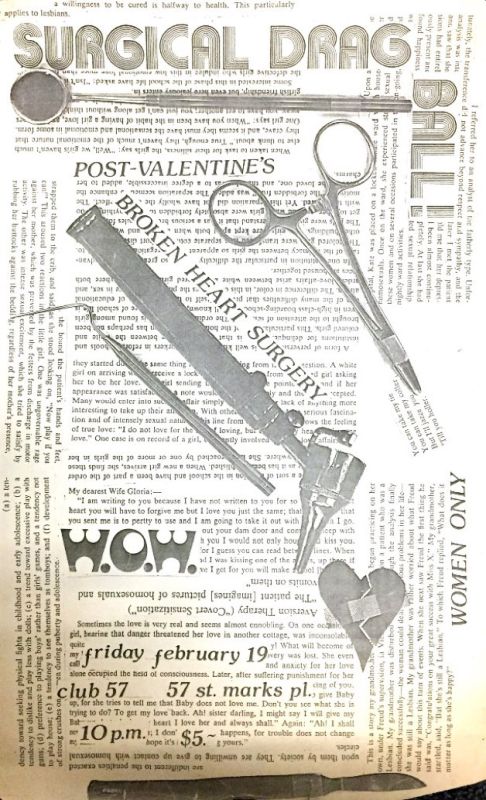

Hannaford and Scully began a Monster Movie Club at Club 57 on Tuesday nights and brought in Ann Magnuson, who became the club’s manager, to curate more performance-based works. Along with Frank Holliday and Andy Rees, they organized a wide variety of experimental events, culling together fledgling artists and entertainers from the East Village, many of whom identified as LGBT, like Ethyl Eichelberger, Lance Loud, and Holly Hughes. Many of the avant-garde performances and events at Club 57 would have strong LGBT affiliations, such as John Sex’s “Burlesk Show,” the Kenneth Anger movie marathon, and the “Women’s Night Surgical Drag Ball” hosted by WOW (Women’s One World) Café Theatre.

By October 1978, Club 57 added a $5 membership fee, for which members received a customized membership card, calendar mailouts, and access to almost any Club 57 event. The fee was instituted to help offset the fact that Club 57 never had a liquor license.

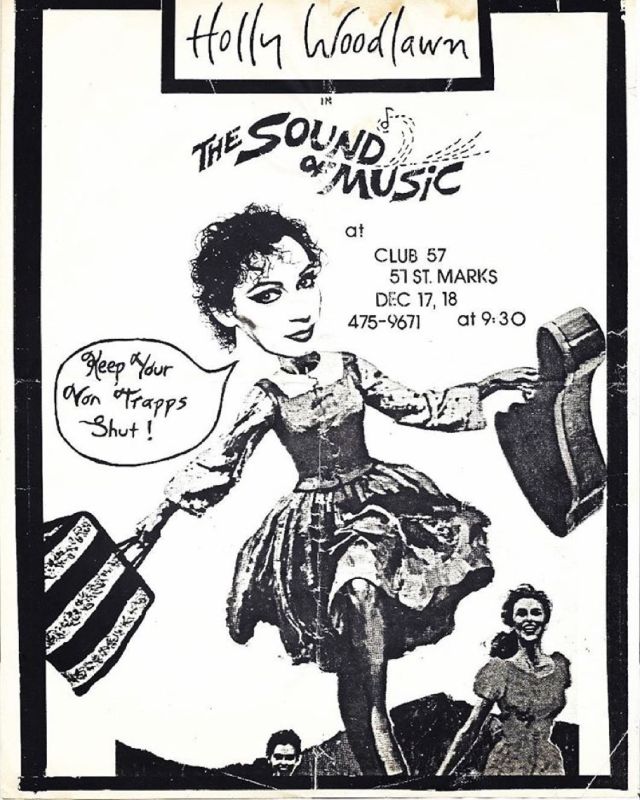

The club became a regular venue and hangout for a bevy of downtown performance and visual artists and musicians, many of whom were LGBT, including Keith Haring, Klaus Nomi, Madonna, Kenny Scharf, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Scott Wittman, Marc Shaiman, Tseng Kwong Chi, Cyndi Lauper, Joey Arias, John “Lypsinka” Epperson (who started doing drag there), Dany Johnson, Fab Five Freddy, Holly Woodlawn (a Warhol superstar), Michael Musto, and April Palmieri.

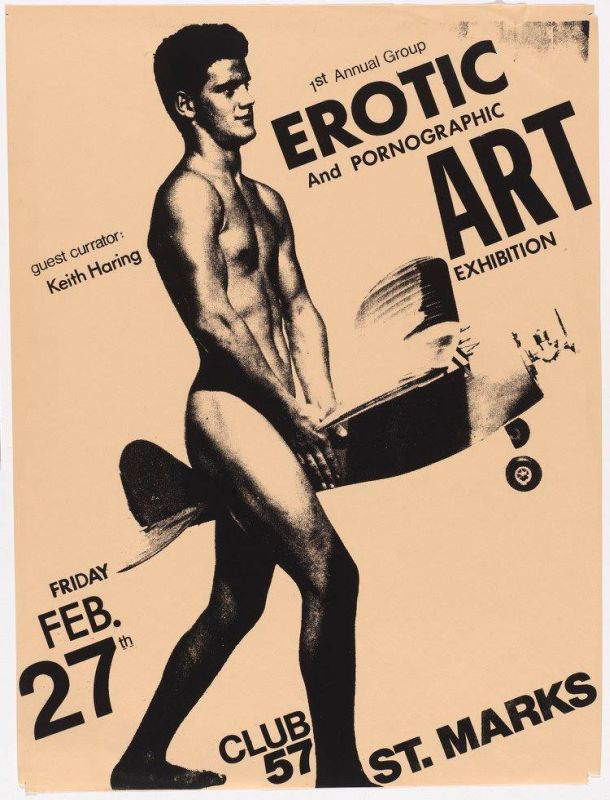

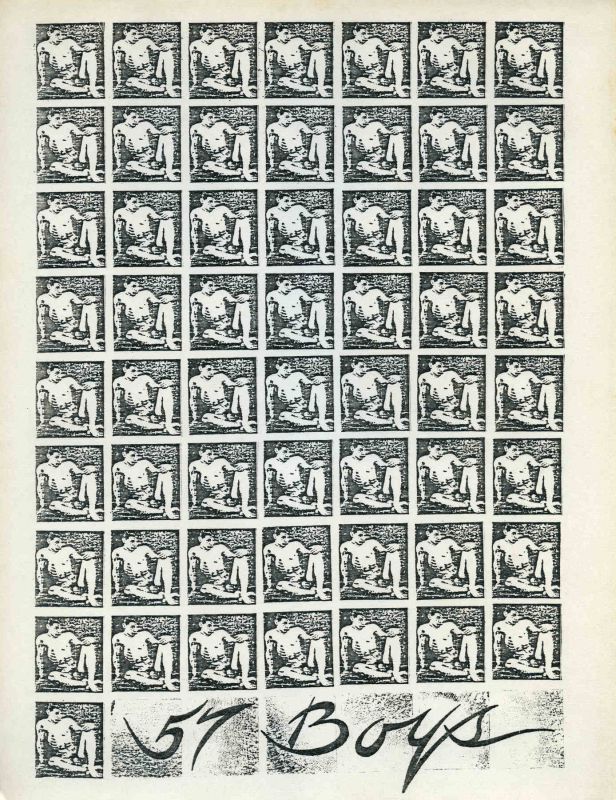

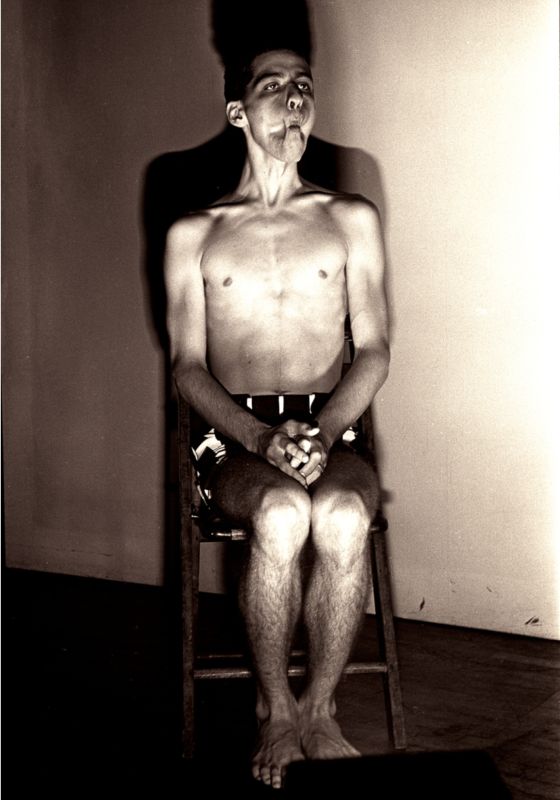

In the summer of 1979, Haring and Scharf became Club 57 regulars and began organizing video screenings and art exhibitions. Haring read poetry, performed inside a fake TV set, debuted his famous “radiant baby” motif, and hosted a “Club 57 Invitational” at which anyone was welcome to make art. One of his most famous shows at Club 57 was the “First Annual Group Erotic and Pornographic Art Exhibition” in February 1981, a particularly graphic exhibition with contributions from dozens of artists and featuring a flyer of a nude man with an airplane between his legs.

Wittman and Shaiman, who later wrote the music and lyrics for Hairspray for Broadway, produced numerous shows at 57, including an original musical called Livin’ Dolls and Wittman’s favorite, The Sound of Muzak, which starred Woodlawn.

Because the place was so small, if you had 25 people in it it felt crowded and if you had 100 it felt like a mob. When we did plays, the audience would be facing one way and — because the club is so small — Scott would yell, ‘Rotate!’ and the audience would have to turn around to see the next set.

In 1981, the Mudd Club’s Steve Maas started recruiting Club 57’s members, including Haring, who curated several shows at Mudd. The two clubs were part of a growing number of downtown clubs that heavily influenced one another, which also included the Pyramid, opened in 1979, and Limbo Lounge and S.N.A.F.U., both opened in 1980, among others. By the early 1980s, many artists who had been members of Club 57 had moved on to larger and more prominent venues. Concurrently, the club, as with many other downtown nightlife venues, was negatively impacted by the AIDS epidemic and rampant drug use, particularly heroin.

On February 1, 1983, Club 57 closed, and the church sold the building in 1988. The Museum of Modern Art held a retrospective in 2017 called “Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978-1983.”

A center of creative activity in the East Village, Club 57 is said to have influenced virtually every club that came in its wake.

In August 2020, Strychacki had a plaque installed on the building exterior, commemorating Club 57 and the 13 individuals who contributed to its influence.

Entry by Marc Zinaman, project volunteer (January 2023; last revised February 2025).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: unknown

- Year Built: 1849-50; c. 1940-44 (facade altered)

Sources

Ada Calhoun, St. Marks is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016).

André-Naquian Wheeler, “An Oral History of Club 57, the Legendary 80s Underground Art Club,” i-D, November 2, 2017, bit.ly/3InISkx.

Brett Sokol, “Club 57, Late-Night Home of Basquiat and Haring, Gets a Museum Worthy Revival,” The New York Times, October 26, 2017, nyti.ms/3GgaRAb.

Clementine Zawadzki, “Tracing the Incredible History of Downtown NY’s Ultimate Party Gallery, Club 57,” Hero, November 30, 2017, bit.ly/3jRq8j3.

Hardeep Phull, “How a Wild, ‘Underground’ Nightclub Inspired a Generation of Artists,” New York Post, October 31, 2017, bit.ly/3ZelTi6.

Jackson Arn, “Against Everything: Club 57 At MoMA,” The Quietus, March 29, 2018, bit.ly/3WVGe9Q.

Ron Magliozzi, Sophie Cavoulacos, J. Hoberman, Jenny Schlenzka, Laura Hoptman, Lucy Gallun, Ann Magnuson, Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2017).

Stanley Strychacki, Life As Art: The Club 57 Story (Bloomington: iUniverse, 2012).

Tim Lawrence, Life and Death on the New York Dancefloor, 1980-1983 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?