Chelsea Hotel

overview

The Chelsea Hotel, the storied residence hotel on 23rd Street, has played host to a succession of countercultures throughout the 20th century, serving as a hub and inspiration for the Beat Generation, Postmodern artists, rock and punk musicians, drag performers, and the Club Kids.

Until 2011, when new developers evicted many long-term residents and began controversial decade-long renovations, the Chelsea was a creative sanctuary that fostered collaboration among numerous LGBT writers, musicians, artists, designers, filmmakers, and actors.

History

Constructed in 1883 when New York’s theater district was centered around 23rd Street, the Victorian Gothic style building was initially one of the city’s first cooperative apartment buildings, but it reopened as a luxury hotel in 1905. With Mark Twain, O. Henry, Oscar Wilde, and Sarah Bernhardt among its earliest guests, the Chelsea quickly acquired a bohemian reputation, which heralded its status in the mid-20th century as New York’s hub for the Beat generation. “There was none of the anonymous impersonal hotel ambiance…I kept meeting people I knew from Europe in the halls,” Beat writer William S. Burroughs recalled. Further contributing to its lore, writers Gore Vidal and Jack Kerouac famously checked into the Chelsea for sex in 1953 after a night out at the San Remo Café and Tony Pastor’s Downtown in Greenwich Village. From the 1970s until his ousting in 2007, manager and part-owner Stanley Bard further cultivated the hotel’s reputation by offering cheap rent to a variety of eccentrics and occasionally accepting art in lieu of rent.

Throughout its life as a literary, musical, and artistic enclave, the Chelsea has been home to many LGBT residents:

Richard Bernstein (1939-2002), a pioneering Pop artist born in the Bronx, lived and worked in the first-floor Grand Ballroom from 1968 until his death. Shortly after moving in, he began working with Peter Hujar and Steve Lawrence on their underground queer Newspaper and its successor Picture Newspaper, famously filling a centerfold with a stylized nude photograph of Warhol superstar and transgender icon Candy Darling. Bernstein is best known, however, for the bold, hyper-colorful covers he created for Interview, the magazine founded in 1969 by Andy Warhol, Gerard Malanga, and John Wilcock. Between 1972 and 1989, Bernstein created nearly 200 celebrity portraits in his distinctively idealized style, which he achieved by embellishing photographs with a blend of materials.

Nick Bienes (b. 1945) and Rhea Gallaher (b. 1952), a couple who write romance novels together under the pseudonym Judith Gould, lived in room 600 from around 1983 to 1995. Shortly after the publication of their first novel, the New York Times bestseller Sins (1982), they moved here, recalling that their friend from the Mineshaft, photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (for whom Bienes was a subject), was a former resident. While at the Chelsea, they wrote six novels, including what is often considered their magnum opus, Never Too Rich (1990), which featured the first gay sex scene in one of their novels.

Gerald Busby (b. 1935) is a prominent composer who moved here with his partner Samuel Byers (1950-1993) in 1977, shortly after composing the scores to Paul Taylor’s iconic ballet Runes (1975) and Robert Altman’s film 3 Women (1977). After they were both diagnosed with AIDS in 1985, and especially after Byers’ death from its complications, Busby struggled emotionally and financially. Assistance from a Guggenheim Fellowship, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and the Estate Project for Artists with AIDS helped Busby recover, however, and he has since written over 600 music pieces (and counting) here.

Bruce Wayne Campbell (1946-1983), known by his stage name Jobriath, is considered by some to be the first openly gay rock musician. His career as a glam rocker lasted only two years due to rampant homophobia and his overhyped persona, but Campbell went on to perform cabaret under a new stage name, Cole Berlin, while living in the rooftop pyramid apartment from 1973 until his AIDS-related death in 1983.

Ching Ho Cheng (1946-1989), an openly gay Chinese-American artist, lived and worked in various apartments here from 1976 until his death. His longtime companion, art historian and educator Gert Schiff (1926-1990), also lived here for over a decade. Finding “beauty and spirituality in the most mundane objects,” Cheng depicted the windows, light switches, floorboards, bathroom tiles, and peeling paint of his rooms in his series of gouache still-life paintings.

Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008), the celebrated English science-fiction writer and futurist, lived in room 1008 intermittently from 1956 to 1977. Referring to the Chelsea as his “spiritual home,” it was the hotel’s creative energy and its residents’ input that drew him here to write the screenplay and novelization of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), one of the most influential films of all time.

Stormé DeLarverie (1920-2014) was a biracial singer, male impersonator, activist, and bouncer who lived on the seventh floor of the Chelsea from the early 1970s until 2010. To read more about DeLarverie, see Stormé DeLarverie Residence at the Chelsea Hotel.

Zaldy Goco (b. 1966), a Filipino-American fashion designer and model, and his boyfriend, the makeup artist Mathu Andersen, lived here for over a decade in the 1980s and 1990s. Both involved in the Club Kids scene, they established their careers by collaborating on looks for RuPaul, including on the music video for his 1993 single “Supermodel (You Better Work),” which propelled RuPaul to international stardom and helped bring drag culture into the mainstream. While here, Goco also had a successful stint modeling women’s clothes for Levi’s, Thierry Mugler, Jean-Paul Gaultier, and Vivienne Westwood.

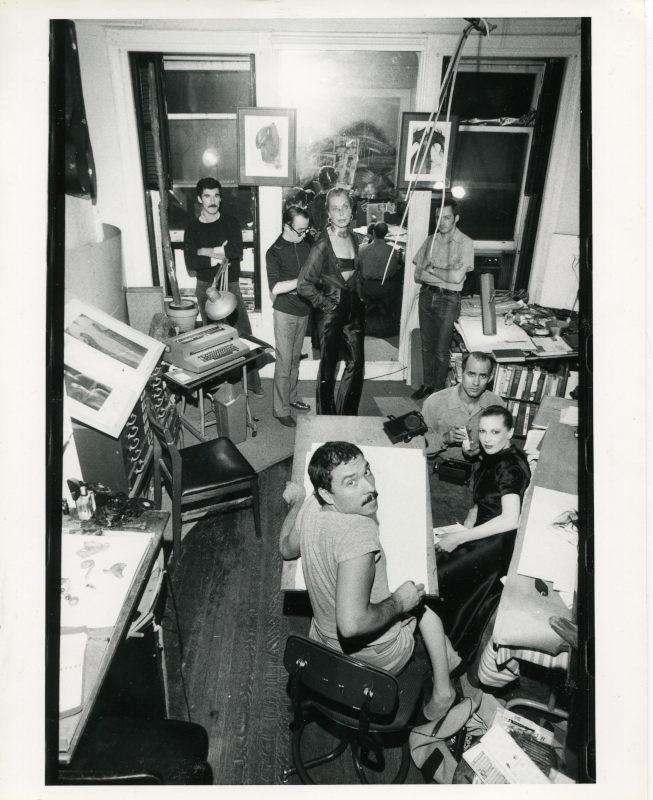

Charles James (1906-1978), widely regarded as the first American couturier and one of the most influential women’s fashion designers of the 20th century, lived and worked in a three-room, sixth floor suite here for the last 14 years of his life. Shortly after moving in, James met fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez and art director Juan Ramos, with whom he would regularly collaborate in late-night sessions, often with Bill Cunningham there to photograph, that took place first at Lopez and Ramos’s studio and then at the Chelsea. In 2001, James’ contributions to fashion were recognized with a plaque on the Fashion Walk of Fame, and a retrospective of his work formed the inaugural exhibition at the Met’s Anna Wintour Costume Center in 2014.

William Ivey Long (b. 1947) is an award-winning costume designer who, knowing that his idol, Charles James, lived here, moved to the Chelsea in 1975 with hopes to work for him. After a persistent six months of sending him notes, Long secured an unpaid apprenticeship with James and worked for him until his death in 1978. While living in room 411, from 1975 to 1980, Long had his Broadway debut as a costume designer on the 1978 revival of The Inspector General, launching a decades-long career of designing costumes for Broadway, opera, ballet, film, and television. By 1980, Long could no longer afford his room here, so he moved to an apartment on West 75th Street.

Lance Loud (1951-2001) was a TV personality, journalist, and punk rock musician who emerged as a public gay figure after his momentous coming out on America’s first reality television series, An American Family, in 1973, which followed the lives of the Loud family. Two years earlier, Loud had left his hometown of Santa Barbara for the Chelsea, well aware of its artistic reputation and ties to his childhood idol, Andy Warhol, with whom he had been communicating since he was 13 years old. When Loud’s mother visited him in the show, he spoke candidly about the loneliness he felt as a child, and he immersed her (and audiences) in the underground, queer culture of New York, introducing her to Hibiscus (né George Harris III) of the Cockettes, Holly Woodlawn, and Jackie Curtis in the transgender play Vain Victory at La MaMa. After the series aired in 1973, Loud moved to the Lower East Side, at which time he became a journalist, later returning to California in 1981, where he continued writing until his AIDS-related death.

Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989), a highly influential photographer of the late 20th century, lived in the Chelsea’s smallest room, No. 1017, from 1969 to 1972 with his girlfriend, the then-unknown poet and musician Patti Smith. While staying here, Mapplethorpe took his first photographs, using a polaroid camera that Chelsea resident Sandy Daley lent him, and met David Croland, who became Mapplethorpe’s first male photo subject and first male lover. The two co-starred in Robert Having His Nipple Pierced, a 1970 experimental documentary directed here by Daley. By 1972, Mapplethorpe was dating art curator and collector Sam Wagstaff, who Croland had introduced him to, and he moved to 24 Bond Street.

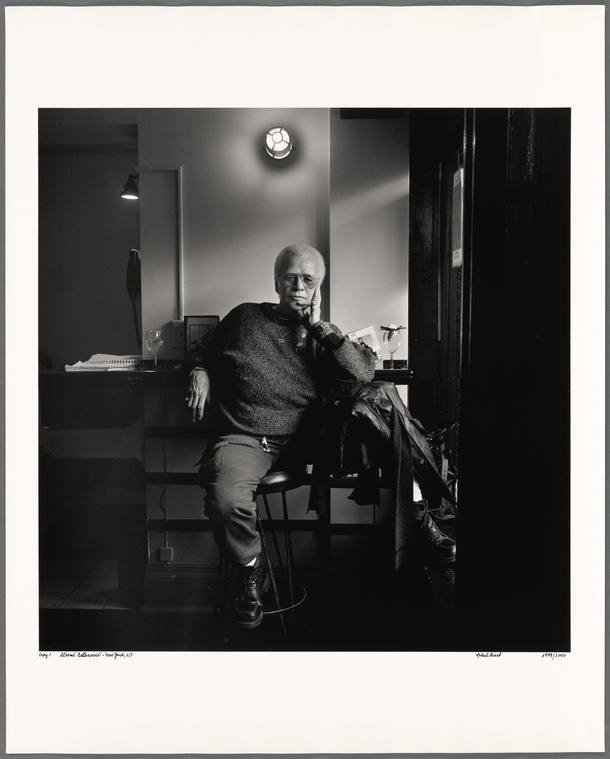

Rene Ricard (1946-2014), a poet, painter, art critic, and actor, lived here intermittently from the late 1960s until his death. “In its cloistered confines,” his obituary read, “he wrote poetry and art criticism, painted experimental oils and nurtured his reputation as a recluse.” While living here, Ricard published four volumes of poetry and, in the 1980s, began to experiment with transforming those poems into paintings. His art criticism introduced the public to the work of emerging artists like Keith Haring, while his acting career included roles in Theater of the Ridiculous performances under the direction of John Vaccaro and Charles Ludlam, multiple Warhol films, and various other underground productions.

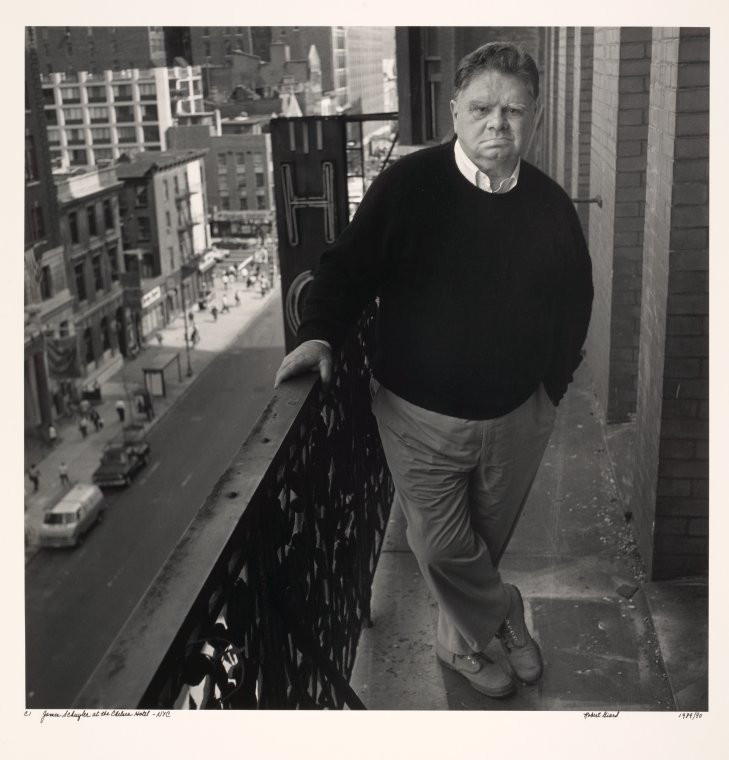

James Schuyler (1923-1991) was a poet central to the New York School, a mid-20th century group of experimental poets and artists. Schuyler briefly lived at the Chelsea around 1954 with the piano duo and couple Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale. He returned in 1979 and lived in room 625 until the end of his life, courtesy of grants from the Frank O’Hara Foundation and other foundations, as well as contributions from friends. During Schuyler’s first year at the Chelsea, writer Eileen Myles served as his assistant, which Myles recounted in the titular story of their first collection of stories, Chelsea Girls (1994). As Schuyler’s struggle with bipolar disorder and diabetes escalated, he became increasingly reclusive, making his room all the more important to him and his poetry. While living here, Schuyler published his Pulitzer Prize-winning poetry collection The Morning of the Poem in 1980, as well as his last major work, A Few Days, in 1985. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1981 and, a few years before his death, had his legendary debut public poetry reading in 1988, at Dia Center for the Arts on Mercer Street.

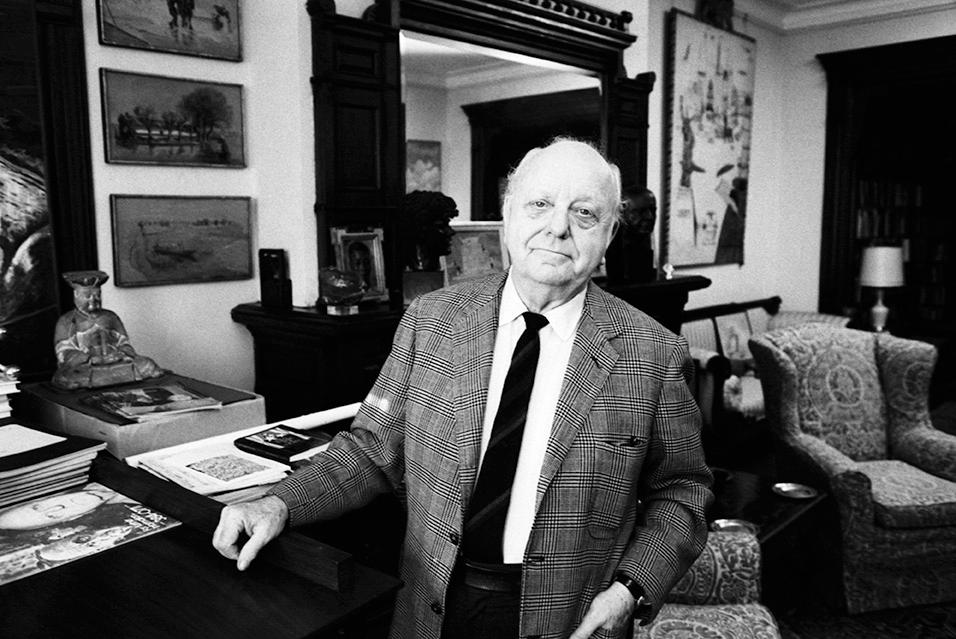

Virgil Thomson (1896-1989), an eminent composer and music critic of the 20th century, lived in a six-room suite on the ninth floor for over half of his life, from 1940 until his death. To read more about Thomson, see Virgil Thomson Residence at the Chelsea Hotel.

Short-Term LGBT Residents of the Chelsea Hotel

The following people lived at the Chelsea for less than five years.

- Dainty Adore, drag performer and opera singer

- Simone de Beauvoir, philosopher

- Brendan Behan, writer

- Sarah Bernhardt, stage actress

- Paul Bowles, composer, and his wife Jane Bowles, artist, who lived here together

- Howard Brookner, filmmaker, and his boyfriend Brad Gooch, author, who lived here together

- William S. Burroughs, author

- Christopher Cox, writer and member of the Violet Quill

- Quentin Crisp, writer

- Isadora Duncan, dancer

- Henry Geldzahler, art curator and critic

- Allen Ginsberg, poet

- Brion Gysin, painter, and John Giorno, poet, who lived here together

- Victor Hugo (né Rojas), window dresser and partner of fashion designer Halston

- Herbert Huncke, writer

- Christopher Isherwood, writer, and his boyfriend Don Bachardy, artist, who lived here together

- Eddie Izzard, comedian

- Charles Reginald Jackson, writer who came to terms with his sexuality while living here with his male lover

- Jasper Johns, artist

- Janis Joplin, rock musician

- John Latouche, lyricist

- Frida Kahlo, artist

- Billy Maynard, photographer, who documented trans and drag performers in the 1970s, including Divine and the Cockettes

- Sinéad O’Connor, singer-songwriter

- Iggy Pop, rock musician

- Dee Dee Ramone, rock musician

- Larry Rivers, artist

- Liz Smith, gossip columnist

- Valerie Solanas, radical feminist who wrote and self-published her SCUM Manifesto here

- Rosa Von Praunheim, filmmaker, who stayed here while filming Tally Brown, New York

- Rufus Wainwright, singer-songwriter, who wrote his second album, Poses, here

- Tennessee Williams, playwright

- Steve Willis, TV director

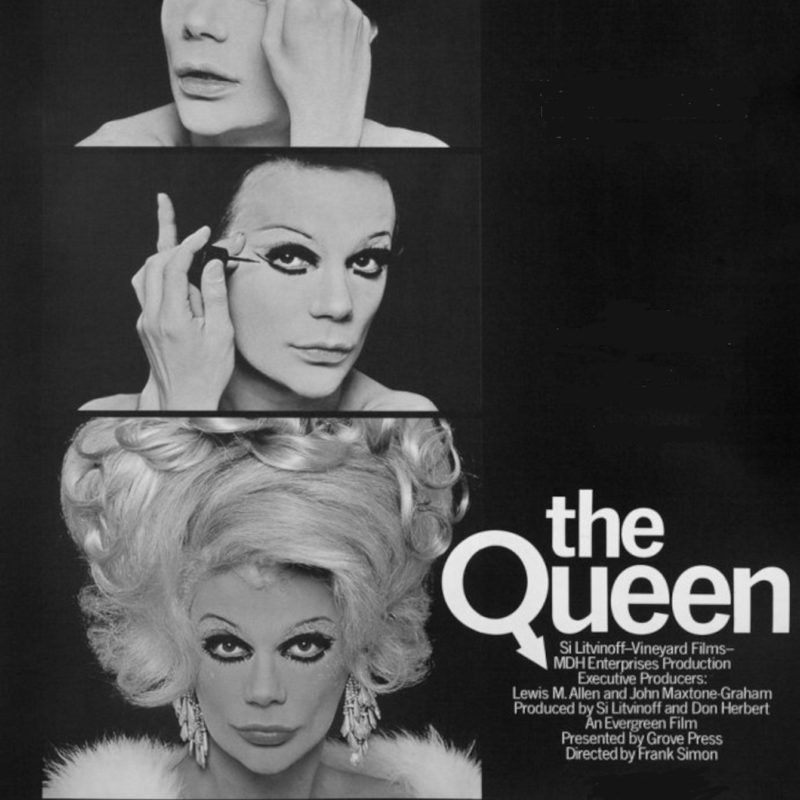

LGBT-Associated Films at the Chelsea

Chelsea Girls (1966), directed by Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey, is an avant-garde film that follows the lives of various Warhol superstars, many of whom resided here. Among those featured in the film were Gerard Malanga, Rene Ricard, Holly Woodlawn, Mario Montez, Paul America, Ondine (né Robert Olivo), Randy Bourscheidt, Ed Hood, and Eric Emerson.

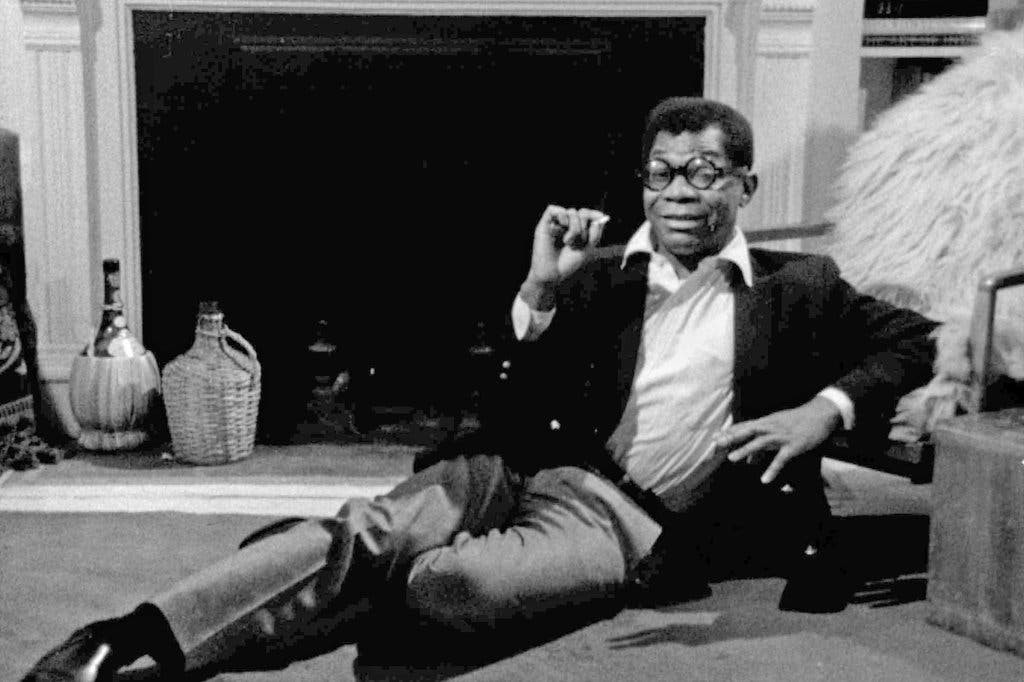

Portrait of Jason (1967), directed by experimental filmmaker and hotel resident Shirley Clarke, is a documentary in which Clarke interviews Black prostitute, hustler, and aspiring cabaret performer Jason Holliday (né Aaron Payne). Regarded as one of the first Black, gay protagonists in film, Holliday is the sole on-screen presence in Clarke’s living room as he narrates his troubled upbringing and struggles with homophobia and racism.

Club Kids at the Chelsea

The Club Kids, many of whom were LGBT, were a group of dance club personalities whose eccentric, flamboyant, gender-bending aesthetic heavily influenced the fashion, art, and pop culture of the 1980s and beyond. Along with Hotel 17 near Union Square and two communal houses in Gramercy Park, the Chelsea became a hub for the Club Kids, due in part to the weekly drag parties that hotel resident Susanne Bartsch hosted at the Savage club in the Chelsea’s basement from 1986 to 1988. Walt Cassidy (b. 1972), an artist known as Waltpaper when involved with the Club Kids, lived in room 215 from 1993 to 1999. Living at the Chelsea, Cassidy said, led to “many interesting collaborative gigs and exciting people entering my orbit.” Party promoter Brooke Humphries (b. 1970) lived on the third floor and, according to her neighbor across the hall, author Ed Hamilton, “she served as the den mother to a large group of Club Kids, mostly young, skinny gay boys,” over a dozen of whom lived in her room.

Among the many other Club Kids who stayed at the Chelsea were Michael Alig, Jason Rail, Christina Superstar, Whillyem Thrillwell, ZAK (né Zachary Augustine), and Peter Gatien’s club designer Impala. Also, throughout the 1980s, early videographer Nelson Sullivan documented the Club Kids at the Chelsea and at the various clubs they frequented, including Webster Hall, the Limelight, and the Tunnel.

Entry by Ethan Brown, project consultant (October 2022; last revised January 2024).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Hubert, Pirrson & Company

- Year Built: 1883

Sources

Charles Herschberg, “Jobriath Revisited: The Return of the First ‘True Fairy,’” Omega One, January 19, 1979.

Claudia Dreifus, “A Conversation With Arthur C. Clarke: An Author’s Space Odyssey and His Stay at the Chelsea,” The New York Times, October 26, 1999.

Claudio Edinger, Pete Hamill & William Burroughs, Chelsea Hotel (New York: Abbeville Press, 1983).

Colin Miller & Ray Mock, Hotel Chelsea: Living in the Last Bohemian Haven (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2019).

Ed Hamilton, Legends of the Chelsea Hotel: Living with the Artists and Outlaws of New York’s Rebel Mecca (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2007).

Gore Vidal, Palimpsest: A Memoir (New York: Random House, 1995).

Homer Layne and Dorothea Mink, The Couture Secrets of Shape: Charles James (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2019).

Leanne Zalewski, “Ching Ho Cheng: A Retrospective,” Artnet (accessed August 3, 2022) bit.ly/3R6qEWl.

Libbie Rifkin, “‘Say Your Favorite Poet in the World is Lying There’: Eileen Myles, James Schuyler, and the Queer Intimacies of Care,” Journal of Medical Humanities (2017), 79–88.

Mark Ford, “The Man Who Came to Dinner,” The New York Review, November 17, 2005 (accessed August 30, 2022), bit.ly/3LXkPc8.

Nadine Hubbs, The Queer Composition of America’s Sound: Gay Modernists, American Music, and National Identity (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2004).

Nathaniel Rich, “An Oral History of the Chelsea Hotel: Where The Walls Still Talk,” Vanity Fair (accessed August 3, 2022) bit.ly/2r1mGnb.

“René Ricard – obituary,” The Telegraph, March 5, 2014.

Richard Bernstein, André Leon Talley & Paloma Picasso, Mega-Star (New York: Grove Press, 1984).

Sherill Tippins, Inside the Dream Palace: The Life and Times of New York’s Legendary Chelsea Hotel (Boston: Mariner Books & Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013).

Walt Cassidy, New York: Club Kids (Bologna: Damiani, 2019).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?