Arnold Lobel Residence

overview

Best known for his 1970s Frog and Toad picture books, heralded as classics of children’s literature, award-winning author and illustrator Arnold Lobel lived in this Park Slope rowhouse from 1973 to the early 1980s.

During this time, he came out as gay to his wife and children, and although he never publicly discussed his homosexuality, it is believed that the characters of Frog and Toad allowed Lobel to quietly express his gay identity.

History

Children’s book author and illustrator Arnold Lobel (1933-1987) developed his natural ability for storytelling as a child while facing ill health, isolation, and bullying in his hometown of Schenectady, New York. He later moved to Brooklyn to pursue a fine arts degree at Pratt Institute, graduating in 1955. After working in advertising, his career in children’s literature began as an illustrator for Harper & Row in 1961. The first book that he both wrote and illustrated was A Zoo for Mister Muster (1962), which established his fondness for featuring animal characters in his stories.

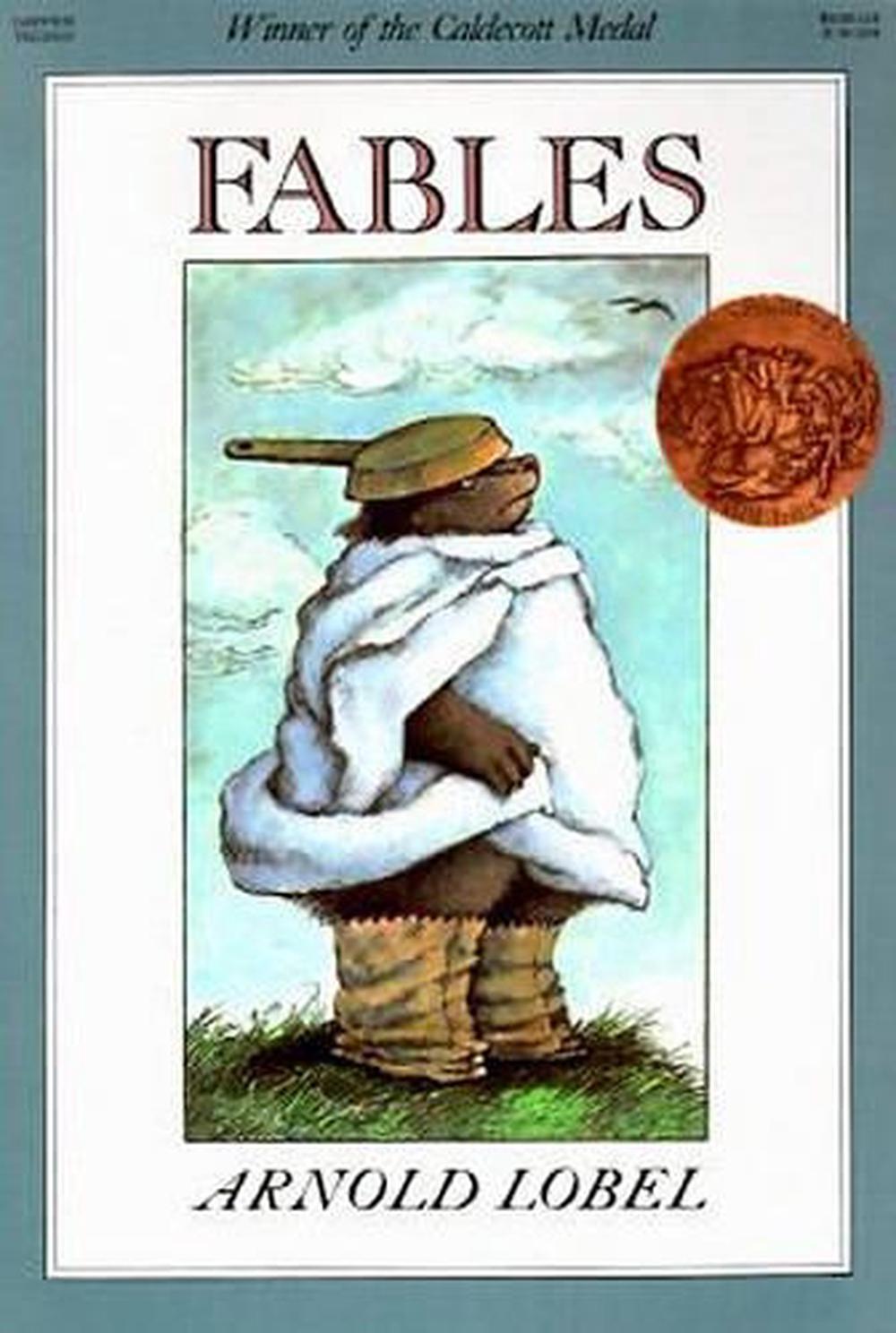

Lobel’s most beloved, acclaimed, and enduring work is the Frog and Toad picture book series, beginning with Frog and Toad Are Friends (1970; Caldecott Honor recipient) and Frog and Toad Together (1972; Newbery Honor recipient). The books were published as part of Harper & Row’s I Can Read series, designed to teach children to read. In 1973, Lobel and his wife, Anita Lobel – his Pratt classmate, fellow children’s book author and illustrator, and sometimes collaborator – purchased the rowhouse at 603 3rd Street in Park Slope, Brooklyn, as their family residence and work studio (they previously lived across the street at No. 618A). From here, Lobel created Frog and Toad All Year (1976) and Days with Frog and Toad (1979), along with many other works, including Mouse Soup (1977) and Fables (1980), the latter of which won the 1981 Caldecott Medal.

The 603 3rd Street house was also where Lobel was living when, in 1974, he came out as gay to his wife and children. Though he never publicly spoke about his homosexuality, and he depicted Frog and Toad as neighbors and best friends, Lobel said that this particular book series was a turning point in his storytelling process because he focused less on a child audience and more on his own feelings. In a 2016 article in The New Yorker, his daughter, set designer Adrianne Lobel, notes that Frog and Toad was the only series of her father’s to feature a relationship, which, regardless of its interpretation, continues to resonate with readers. She also describes the series as being ahead of its time by showing characters of the same sex who loved each other, adding “I think ‘Frog and Toad’ really was the beginning of him coming out.” In a 2021 Homerton College Library blog post, the author writes that these books “evoke an intimacy which was often too controversial to articulate in the rigidly heterosexist arena of children’s culture.” Perhaps the use of non-human characters helped disguise this intimacy, as children’s book author and illustrator Tull Suwannakit told Slate in 2020: “The use of an animal character in place of a human allows room for imagination and wonder to take place, breaking away the taboo and restraint.”

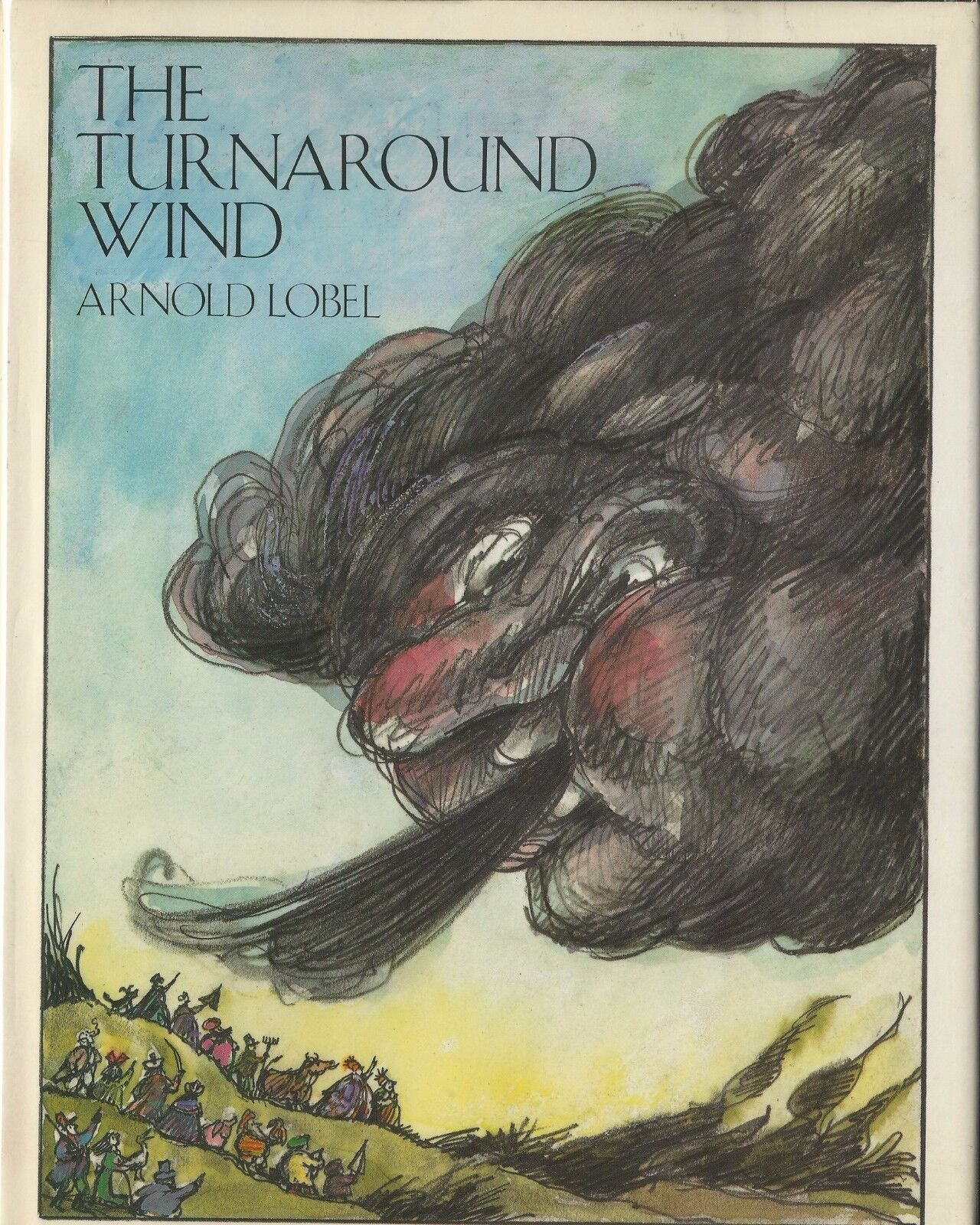

In the late 1970s, while Lobel was working on his final Frog and Toad book, he met Howard Weiner, who would become his partner. Lobel, having separated from his wife, moved to Greenwich Village in the early 1980s and lived in an apartment at 32 Washington Square West. He died in 1987 at age 54, though his New York Times obituary did not mention the cause was AIDS (a common omission in the early years of the AIDS epidemic) and that Weiner cared for him during his illness. Lobel’s final picture book, The Turnaround Wind (1988), was published posthumously. According to the Homerton blog, “Its strange story of a sudden storm descending on a community of people and turning everything upside-down makes an obvious allegory for the AIDS crisis that caused Lobel’s death.”

Over the course of his celebrated, though comparatively short, career, Lobel illustrated nearly 100 books, many of which he also authored. The Frog and Toad series, in particular, remains a staple of early childhood reading and education.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (November 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Undetermined

- Year Built: By 1888

Sources

Arnold Lobel, interview with Roni Natov and Geraldine Deluca, The Lion and the Unicorn, vol. 1, no. 1, 1977, pp. 72-96.

Brandon Zachary, “The Lobels on the Frog and Toad Movie That Never Happened and What Made Apple Ideal for the New Series,” CBR, June 17, 2023, bit.ly/40cxP4v.

Colin Stokes, “’Frog and Toad’: An Amphibious Celebration of Same-Sex Love,” The New Yorker, May 31, 2016, bit.ly/45Mhi8T. [source of Adrianne Lobel quote]

David W. McCullough, “Arnold Lobel and Friends,” The New York Times, November 11, 1979, BR14.

Hilary Stout, “Arnold Lobel, Author-Illustrator,” The New York Times, December 6, 1987, 61.

James Marshall, “Arnold Lobel,” The Horn Book Inc., May 1, 1988, bit.ly/3Qva5W1.

Jesse Green, “The Gay History of America’s Classic Children’s Books,” The New York Times, February 7, 2019, bit.ly/3Qb6riR.

Kyle Lukoff, “Frog and Toad Were More Than Friends: A Guest Post by Kyle Lukoff,” School Library Journal, July 14, 2020, bit.ly/3MgmGKt.

“LGBT+ History Month 2021: Celebrating Arnold Lobel,” Homerton College Library weblog, February 17, 2021, bit.ly/3Sd8VzL. [source of Homerton quotes]

Michael Patrick Hearn, “Arnold Lobel: An Appreciation,” The Washington Post, January 10, 1988, bit.ly/470t4gI.

Phillip Maciak, “Frog and Toad and Me,” Slate, July 3, 2020, bit.ly/45MS3mO. [source of Tull Suwannakit quote]

Teya Rosenberg, “Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad Together as a Primer for Critical Literacy,” in Julia L. Mickenberg and Lynne Vallone, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?