Antonia Pantoja Residence

located in the Morningside Gardens complex

overview

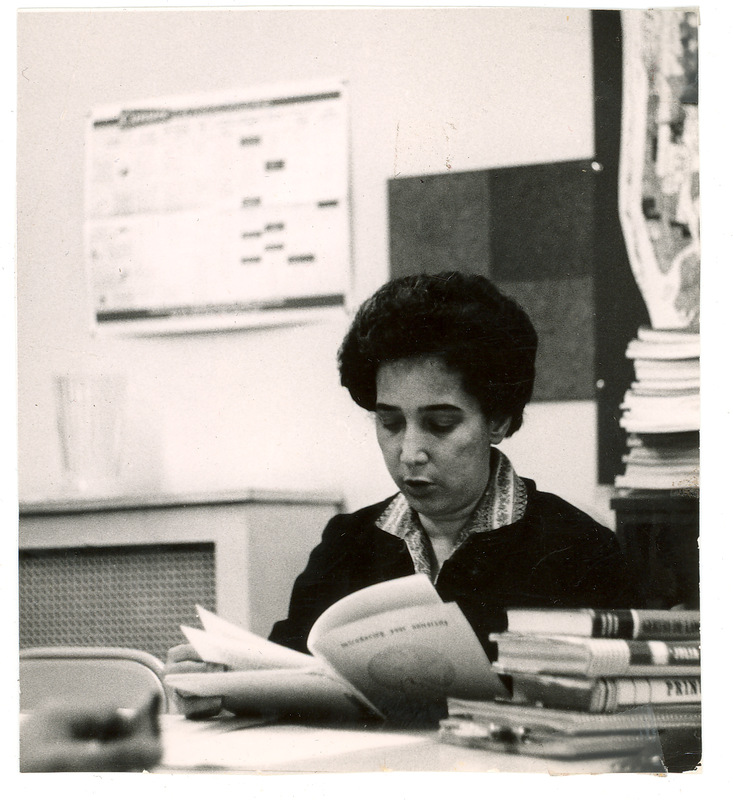

Recognized as a beacon for the Puerto Rican and Latino communities in New York City, Antonia Pantoja founded various groundbreaking institutions dedicated to educating and advancing minority youths through multiple services.

Pantoja lived in an apartment in the Morningside Gardens complex in Morningside Heights from the late 1950s until early 1969 while she organized communities, established institutions, and taught at Columbia University’s School of Social Work.

History

Coming from a working-class family in the barrio of Santurce in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Antonia Pantoja (1922-2002) taught in rural schools for two years until November 1944, when she joined the first wave of Puerto Rican migration to New York City. She initially lived in a Lower East Side tenement at 123 Baruch Place (demolished) with her partner Helen Lehew and other acquaintances, and both eventually moved to an apartment building at 152 East 97th Street (demolished). In the early 1950s, Pantoja began working at the 110th Street Community Center and attended Hunter College. During her studies, she interacted with other Puerto Rican students and fellow migrants, noticing the limitations that Puerto Rican — and, in her case, Black Puerto Rican — migrants faced in the city. To address these issues, she established the Hispanic Young Adult Association (HYAA) in 1953, later renamed the Puerto Rican Association for Community Affairs.

Pantoja began her studies at Columbia University’s School of Social Work and graduated in 1954. In the latter half of the decade, Pantoja was hired by the New York City Commission on Intergroup Relations (now known as the Commission on Human Rights), where she headed an intergroup relations and tension control department. This experience inspired Pantoja to develop the Puerto Rican-Hispanic Forum, later renamed the Puerto Rican Forum. The Forum highlighted one of Pantoja’s lifelong goals: building institutions focusing on the needs of the Puerto Rican community in New York City.

Very early in my work in the community, it became evident that we Puerto Ricans needed to build institutions that would provide for our needs in a manner that we could use them […] we needed to build our own institutions.

Pantoja and Lehew separated in the late 1950s, and Pantoja bought a cooperative apartment in Morningside Gardens at 70 La Salle Street in Morningside Heights. While living in Morningside Gardens, Pantoja continued developing institutions and working around the city: she hosted meetings of the Puerto Rican Association for Community Affairs (PRACA) in her living room, and by 1961, was appointed as the first director of ASPIRA, the project she considered her most important and impactful. ASPIRA focused on educating and providing leadership opportunities for Puerto Rican youth, opening chapters in other states and Puerto Rico. It championed a lawsuit against the New York City Board of Education that demanded bilingual education in the city.

Pantoja resigned from ASPIRA in 1966 to teach at the Columbia University School of Social Work. During this period, Pantoja became a member of various institutions, such as the Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited–Associated Community Teams (HARYOU-ACT) board. She also served as a representative for the Puerto Rican community at the 1967 New York State Constitutional Convention.

Facing health problems, Pantoja briefly returned to Puerto Rico in January 1969 with then-partner Barbara Blourock before moving to Washington, D.C., in July 1971. After completing her doctorate in Ohio, she spent the next 30 years in California and Puerto Rico with her partner Wilhelmina Perry, founding educational institutions and community programs.

In 1996, Pantoja became the first Puerto Rican woman to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. She returned to New York with Perry in 1999. Pantoja rarely mentioned her relationships with Lehew, Blourock, and Perry until her memoirs, published posthumously.

Although I have not discussed directly my sexuality, I am also at peace with this part of me. I have decided not to discuss it in this book because I have always drawn a line between my private and public life. However, I wish to eliminate the possibility of being misinterpreted and being described as secretive about this matter.

Pantoja has been recognized by various universities in Massachusetts, New York, and Puerto Rico. She is considered a trailblazer in improving the education and general well-being of Puerto Rican and Latino youth.

Entry by Andrés Santana-Miranda, project consultant (July 2024)

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Wallace K. Harrison and Max Abramovitz

- Year Built: 1954-1957

Sources

Amalia Duarte, “Portrait of a Pioneer: Dr. Antonia Pantoja,” The Hispanic Outlook in Higher Education 4, no. 13 (May 1, 1994): 11.

Antonia Pantoja, Memoir of a Visionary: Antonia Pantoja (Houston: Arte Público Press, 2002). [source of second pull quote].

Antonia Pantoja Papers, Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY.

Lourdes Torres, “Boricua lesbians: Sexuality, nationality, and the politics of passing,” CENTRO Journal XIX, no. I (Spring 2007): 231-249.

Lourdes Torres, “Queering Puerto Rican Women’s Narratives: Gaps and Silences in the Memoirs of Antonia Pantoja and Luisita López Torregrosa,” Meridians 19 (Supplement 2020): 279-307.

Victoria Núñez, “Reading Puerto Rican Migration in the Autobiography of Antonia Pantoja,” Sargasso II (2005-2006): 77-91.

Wilhelmina Perry, “Memorias de una Vida de Obra (Memories of a Life of Work): An Interview with Antonia Pantoja,” Harvard Educational Review 68, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 244-258. [source of first pull quote].

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?