Dakota Apartments

overview

The Dakota, the famed apartment building on Central Park West, has long been a home for celebrities, including notable LGBT people in the arts.

Former residents include composer Leonard Bernstein, poet Charles Henri Ford, actress Judy Holliday, playwright William Inge, and ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev.

History

Constructed in 1884 in the German Renaissance Revival style, the Dakota Apartments was the city’s first major upper-middle class apartment house. The building was a project of Edward Clark whose fortune came from the Singer Sewing Machine Company. He died in 1882, during construction, and work was completed by his son Alfred Clark (1844-1896), who moved into the Dakota. Although married with four sons, he had long led a double life, spending his summers in Europe with the love of his life, Norwegian tenor Lorentz Skougaard, from 1866 until Skougaard’s death in 1885 (Clark kept an apartment for Skougaard on West 22nd Street near his own rowhouse). A bereft Clark commissioned a memorial sculpture for Skougaard’s grave in Norway from George Grey Barnard on whom Clark had an apparently unrequited crush. Clark’s biographer Nicolas Weber describes Barnard’s homoerotic “Brotherly Love” as “two muscular, athletic, naked men – in the vein of Michelangelo’s greatest slave figures.”

During the 20th century, the Dakota attracted many people in the arts as residents, some of whom included these LGBT notables:

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) was a prominent composer and conductor for live performance whose last residence was the Dakota, moving there with his family in 1975. Two of his former residences included the Studio Towers atop Carnegie Hall and the Osborne Apartments. By the time Bernstein moved to the Dakota, he had resigned as music director of the New York Philharmonic in order to pursue composing; however, he continued to conduct all over the world. Perhaps his most famous concert was in December 1989 when he led an ensemble of international musicians, including those from the former East and West Berlin, in an internationally televised rendition of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, substituting the word Freiheit (freedom) for Freude (joy), in celebration of the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 1976, Bernstein left his wife, Felicia Cohn Montealegre, and moved in with composer Tom Cothran, but shortly thereafter, Montealegre was diagnosed with cancer and Bernstein returned and nursed her until she died in 1978. While living at the Dakota, Bernstein received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1980. His final concert was at Tanglewood in 1990, shortly before his death.

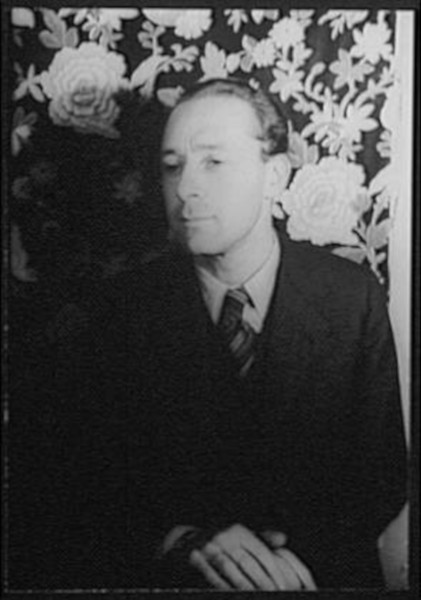

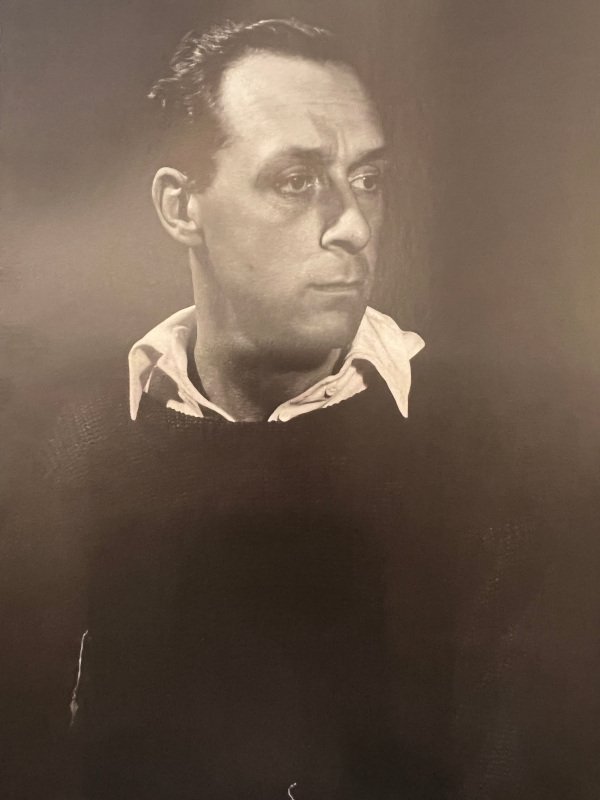

Charles Henri Ford (1908-2002) was a poet, artist, editor, and filmmaker who lived at the Dakota between extensive periods of time abroad, from about 1959 until his death. In 1933, he and Parker Tyler (who was likely his lover) co-wrote The Young and Evil, which Gore Vidal noted was “doubtless the first and still most crucial queer novel written.” The 1986 American publication of the book included drawings from Ford’s partner of 24 years, the Russian painter Pavel Tchelitchew (1898-1957), which he originally drew for Ford’s private collection. Ford and Tyler also created View (published 1940-47), the influential arts magazine that introduced surrealism to the United States. Over his career, Ford collaborated with LGBT notables such as Djuna Barnes (who was also his lover), Andy Warhol, and Gertrude Stein.

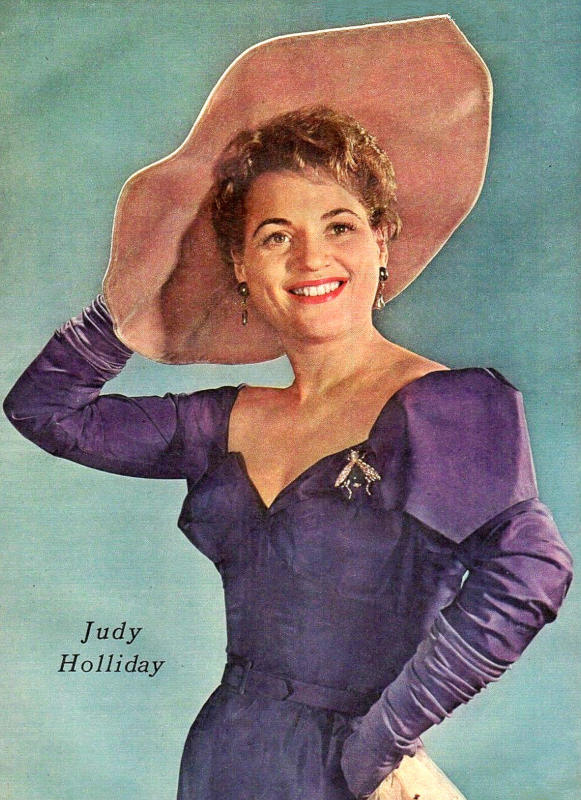

Judy Holliday (1921-1965) was an actress and singer who lived in the Dakota from 1953 until her untimely death from cancer. She was born Judy Tuvim — tuvim in Hebrew means “holiday,” which inspired the stage name she was told to use to mask her Jewish identity, as other Jewish entertainers did at a time when anti-Semitism was particularly rampant. In 1950, she won an Academy Award for her role as Billie Dawn in the George Cukor-directed Born Yesterday, which she had also performed on Broadway. In 1957, she won a New York Drama Desk Award and a Tony Award for her performance in Bells Are Ringing. Buddy Kent, a drag king at several downtown clubs in the 1940s, noted that Holliday hung out at these clubs and “was going with a female who was a cop.” Holliday’s ten-year marriage to David Oppenheimer ended in divorce in 1958.

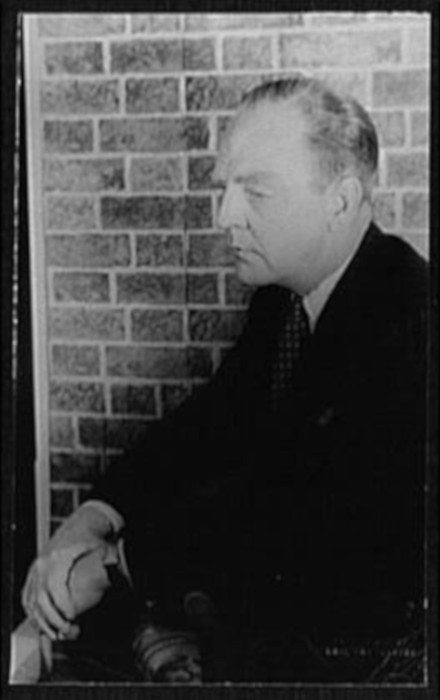

William Inge (1913-1973) was the most successful American playwright of the 1950s, the same era he was living in the Dakota. Known as the “Playwright of the Midwest” for his portrayals of small-town America, Inge wrote a number of Broadway hits, including his first play, Come Back, Little Sheba (1950), the Pulitzer Prize-winning Picnic (1953), and the Tony-nominated plays Bus Stop (1955) and The Dark at the Top of the Stairs (1957). All received film adaptations. His original screenplay for Splendor in the Grass (1961) earned him an Academy Award. Inge, though closeted, wrote three plays that dealt with gay subject matter: The Boy in the Basement (1962), written in the 1950s, overtly addressed homosexuality, while Where’s Daddy (1966) and The Last Pad (1972) each featured a gay character.

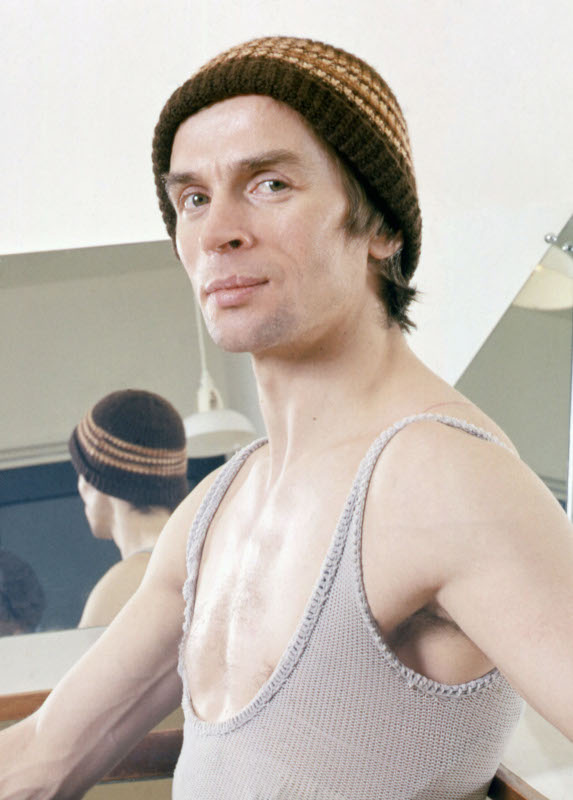

Rudolf Nureyev (1938-1993), widely considered the greatest male ballet dancer of his generation, was born in the Soviet Union, defected to the West in 1961, and lived in the Dakota from at least 1975 until his death, though he spent most of his time in Paris. He performed in such productions as The Sleeping Beauty, Don Quixote, Swan Lake, and The Nutcracker. The American Ballet Theatre notes that Nureyev was “the first male superstar of the ballet world since Vaslav Nijinsky. He mesmerized audiences with spectacular leaps and turns, but it was his passionate temperament and flamboyance onstage and off that made him a phenomenon.” Nureyev, who often performed at the nearby Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, traveled the world as a guest dancer and, later, a choreographer. In 1984, he was diagnosed with HIV, dying from AIDS-related complications nine years later. The Rudolf Nureyev Dance Foundation in the United States and the Rudolf Nureyev Foundation in Europe were established to promote classical dance.

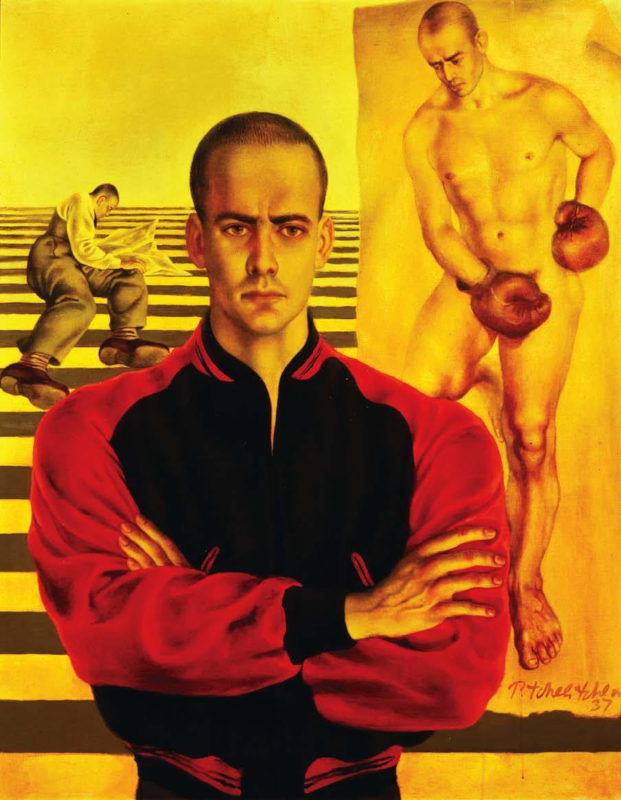

Pavel Tchelitchew (1898-1957) was a Russian-born painter and costume and set designer. After leaving Russia, he lived in Paris, where he encountered Gertrude Stein and ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev. He designed sets and costumes for both Diaghilev and ballet choreographer George Balanchine. He met writer Charles Henri Ford in Paris and they moved to New York in 1934 and into the Dakota in 1959. Tchelitchew was among the first living artists whose work was displayed at the new Museum of Modern Art, which also owns his best-known work, the Surrealist painting Hide and Seek (1942). He also painted many highly eroticized portraits of young men, including one of Lincoln Kirstein in 1937.

Playwright Mart Crowley (b. 1935), best known for his play The Boys in the Band (1968) was refused by the Dakota’s notoriously picky coop board, reportedly because he was an out gay man.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager, and Andrew Dolkart, project director (July 2019; last revised June 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Henry J. Hardenbergh

- Year Built: 1880-84

Sources

Carol Vogel, “To the Highest Bidder, From Nureyev’s Life: To the Highest Bidder, From Nureyev,” The New York Times, January 7, 1994, 13.

Charles Henri Ford Papers, Online Archive of California, bit.ly/2LOr1WU.

Christine Haughney, “Sharing the Dakota with John Lennon,” The New York Times, December 6, 2010, A29.

Diana Bertolini, “A Disturbed Genius Seen Through the Eyes of an Intimate Friend: William Inge and Barbara Baxley,” blog, The New York Public Library, on.nypl.org/2YUijdq.

Elisabeth Kley, “Fabulous Ford,” artnet, bit.ly/2NPBZ0U.

Felice Picano, “Why We Remember Charles Henri Ford,” The Gay and Lesbian Review, March 14, 2018, bit.ly/2NLIh1o.

Georg Predota, “Interlude: Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre: A Divided Life,” Interlude, bit.ly/2w0Ifax.

Irene Dash, “Judy Holliday,” Jewish Women’s Archive, bit.ly/2xPgaDz.

Lisa E. Davis, “The Red Scare’s Lesbian Informant,” Advocate, April 7, 2017, bit.ly/2XZyuc3. [source of Kent quote]

Nicholas Fox Weber, The Clarks of Cooperstown (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007).

Nigel Simeone, ed., The Leonard Bernstein Letters (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

Steve Dalachinsky, “For Charles-Henri Ford— Another I Did Not Know,” The Brooklyn Rail, April 1, 2003, bit.ly/2YNEXUE.

“Rudolf Nureyev,” American Ballet Theatre, bit.ly/2LPFQbw. [source of American Ballet Theatre quote]

“Rudolf Nureyev’s Short Biography,” The Rudolf Nureyev Foundation, bit.ly/2G8MzKb.

“William Inge Biography,” William Inge Center for the Arts, bit.ly/1VRDhUk.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?