Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater / Club 181 / Phoenix Theater

also known as the Club 181 and the Phoenix Theater

overview

The Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater, a former Yiddish theater, was the location of the Mafia-controlled Club 181 (1945-51), known for its lavish shows of “female impersonators” (a term used at the time) and “drag king” staff, and the pioneering Off-Broadway Phoenix Theater (1953-61).

See Peter Hujar Residence & Studio / David Wojnarowicz Residence & Studio for more information on this site’s LGBT history.

History

The Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater is the single most tangible reminder of the heyday of Yiddish theater in 20th-century New York, when venues of this kind lined lower Second Avenue. Except for a few years when it operated as a movie theater, the building was used continuously as a Yiddish theater from its opening in 1926 until 1945.

After the theater’s completion, the downstairs, entered at the south end of the building, was the location of a series of ethnic clubs, all featuring live entertainment: Russian Art Restaurant (1927-40), Adria (Polish) Restaurant (1940), Club Adria (1941), Club 181 (1941-42), an “outpost of Harlem swing,” and the Roumanian Folks Casino (1944-45).

Club 181

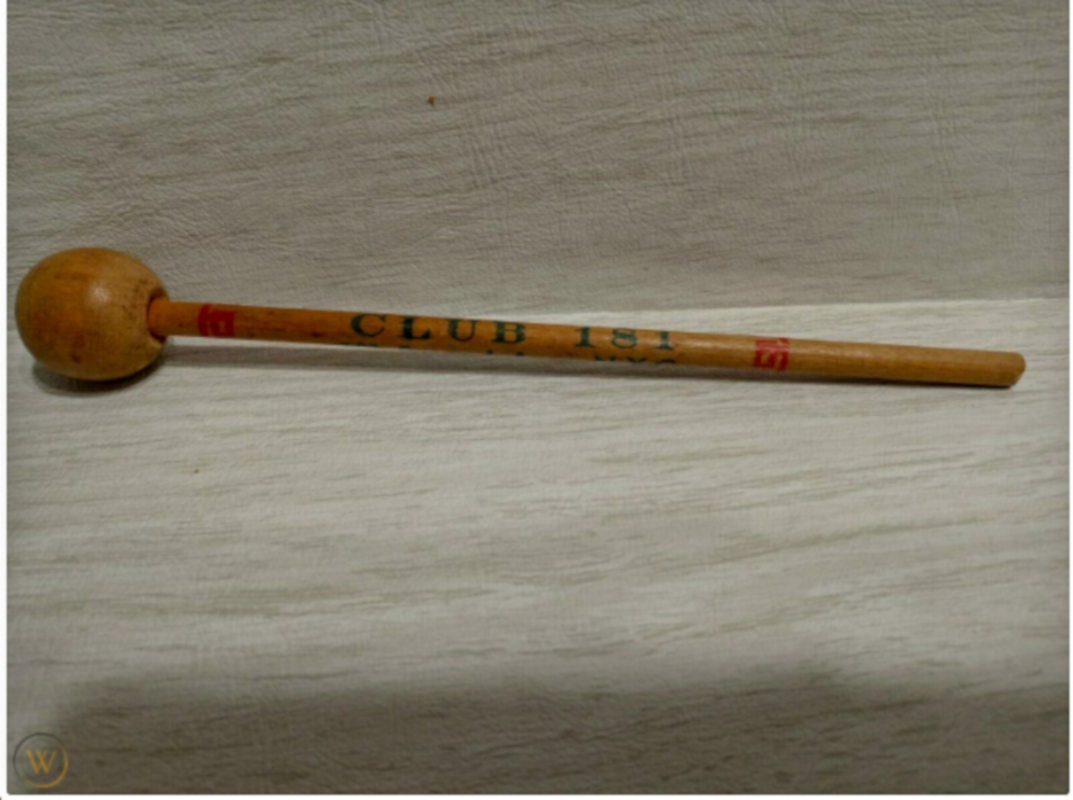

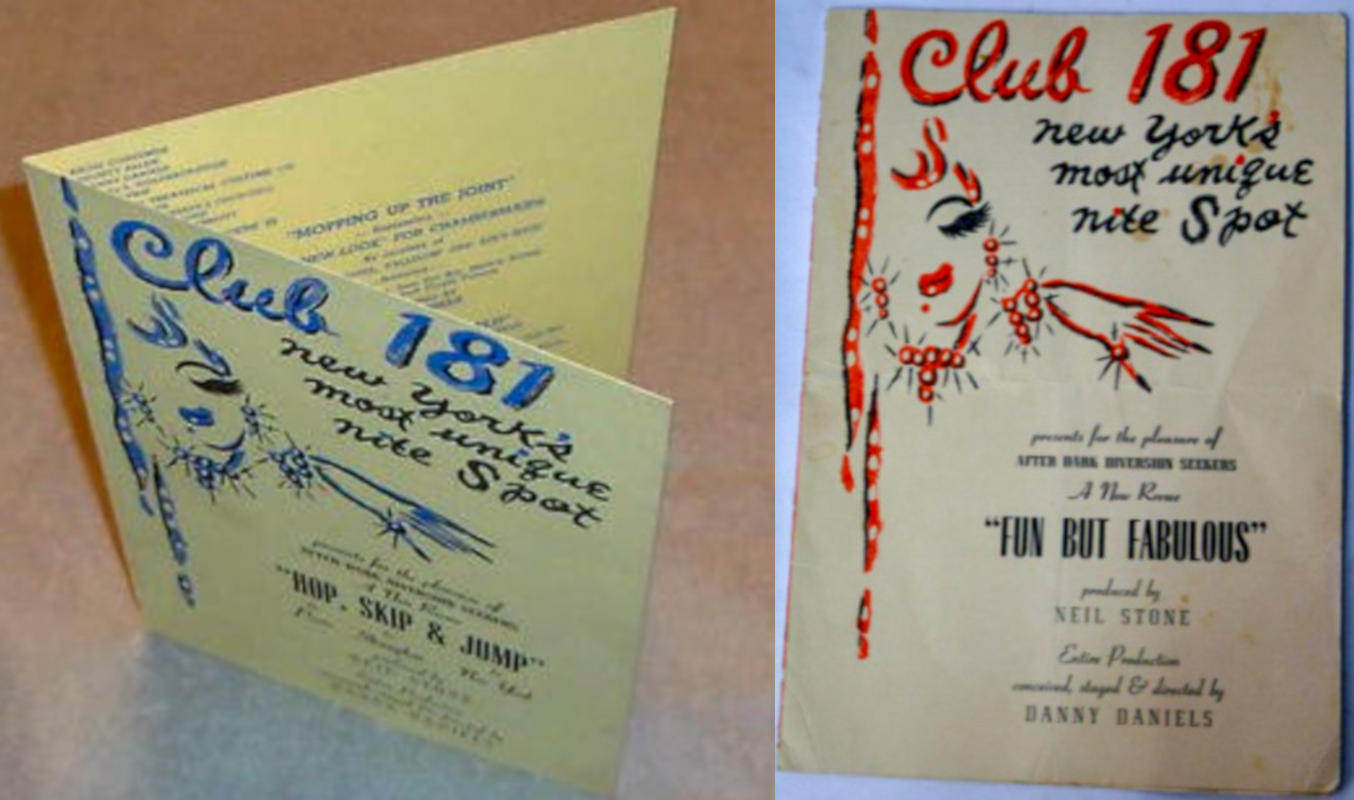

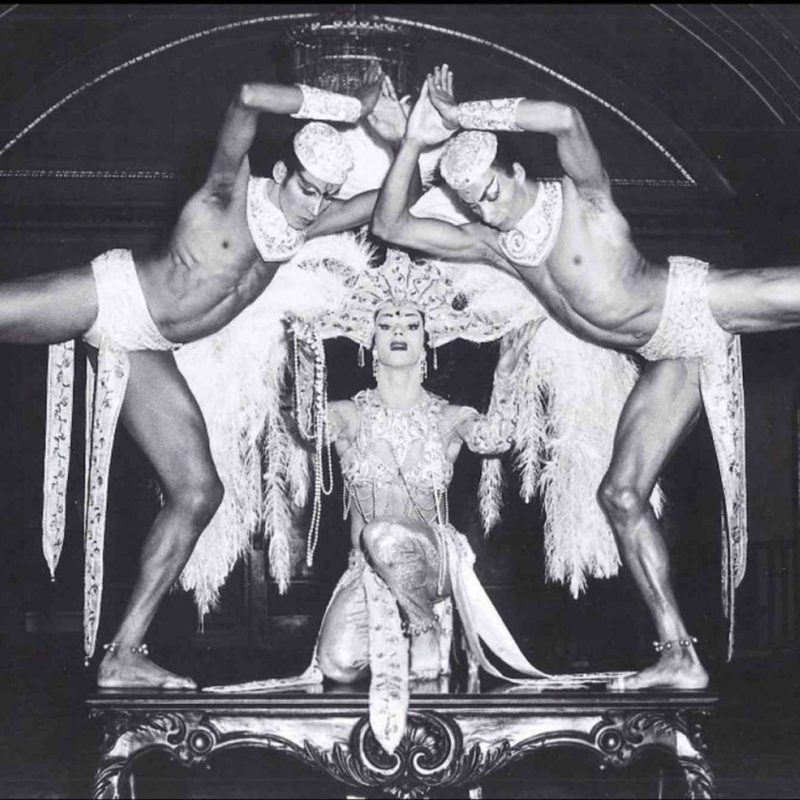

From 1945 to 1951, this was the popular Mafia-controlled Club 181, called “the homosexual Copacabana” as it was one of the most luxurious clubs in the U.S. that featured lavish shows of “female impersonators” (a term used at the time) and “drag king” wait staff and performers. Three shows performed nightly were produced by Neil Stone and “conceived, staged, and directed” by Broadway dancer (and later Tony Award-winning choreographer for stage, as well as film and TV) Danny Daniels. Live music was provided by the orchestra of prolific Broadway conductor and musical director Al Goodman. Among notable performers at Club 181 were “Kitt Russell” (Russell Paull), later the director of the Club 82 Revue, who got his start here in 1948; drag kings Buddy Kent, Gail Williams, and Blackie Dennis; and lesbian stripper Toni Bennett.

It was called “the most famous fag joint in town” by Jack Lait and Lee Mortimer in their homophobic book U.S.A. Confidential in 1952.

[The 181 Club had] waiters who were butch lesbians in tuxedos. … Like the bars of the 1920s, it drew many heterosexuals who came to gawk or to dabble, but many more men and women who were committed to homosexuality and who came to be with other homosexuals.

Club 181 was opened by the family of the infamous Mafia boss Vito Genovese, who was one of the bigger Mafia club operators in Greenwich Village starting in the 1930s. Anna Genovese (1905-1982), Vito’s bisexual wife, ran it with her brothers Pete and Fred Petillo, and Genovese frontman/manager Stephen Franse. Anna had started out in clubs as the proprietor of Club Caravan, 578 West Broadway (demolished) in 1939, taking over many of her husband’s business interests when he left New York City for exile in Italy in 1937 to avoid arrest for a murder and other crimes. She lived at 29 Washington Square West, above Eleanor Roosevelt.

The club, however, lost its liquor license through an action of the New York State Liquor Authority (SLA) in April 1951. For five nights – December 15 through 19, 1950 – the club, its performers, staff, and patrons were surveilled by undercover police. The club was then cited for nine violations, including the sale of alcohol after hours; staff allegedly inducing patrons to buy alcohol; the club permitting an “indecent” act by a patron; the presence of “homosexuals,” lesbians, and other “undesirables;” and the club put on “obscene, indecent” performances and exhibitions. In its report, the New York Daily News called the club “a hangout for perverts of both sexes.”

Club 181 was extremely profitable, with a substantially straight outer borough and tourist crowd, and receipts for 1950 were reported as $480,000. The Mafia, through the 181 Restaurant Corp., with Stephen Franse as president, contested the revocation of its license. The case was heard in New York Supreme Court on March 28 and April 11, 1951. The counsel for the SLA stated “the operation of this club constituted an affront to the community and a danger to the morals of the citizenry,” and much of the police testimony centered on the gender non-conforming dress and behavior of the performers, staff, and patrons. Franse was forced to deny any knowledge that gay men or lesbians frequented the club or were employed there. Interestingly, the club attempted to challenge the SLA’s use of the term “disorderly” (in Section 106 of its law) to revoke the licenses of places with an LGBT clientele, since it was so vague and the Legislature had never defined it. Club 181’s license was officially revoked on April 27, then it was stayed until review by the court’s Appellate Division, which denied the appeal on June 6. The New York State Court of Appeals affirmed the earlier decision on July 11, and the club’s final appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was denied.

Club 181’s operation was basically transferred to Club 82, 82 East 4th Street, in 1953.

Phoenix Theater

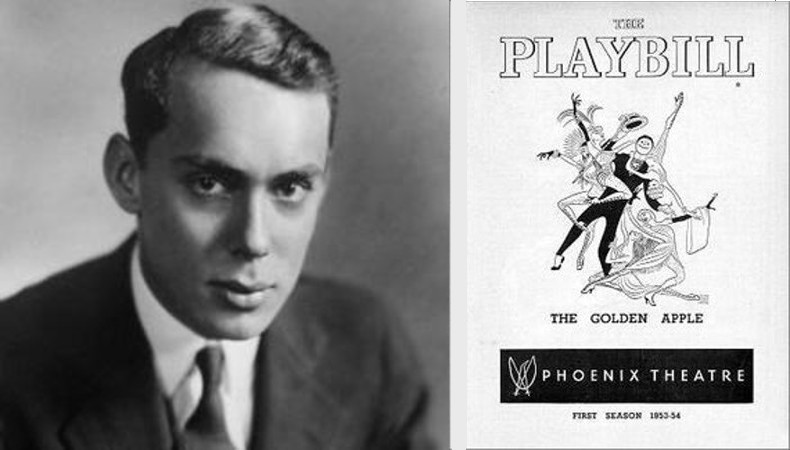

The building was particularly renowned from 1953 to 1961 as the pioneering Off-Broadway Phoenix Theater. One of the most important, prolific, and creative companies of the time (also named the Phoenix Theater), it was founded by Norris Houghton, who had experience in theater design and direction, and T. Edward Hambleton, descendant of a wealthy Maryland banking family who had theater management/production experience. Houghton became the artistic director and Hambleton the manager. Formed initially as a limited partnership company, its partners included such theatrical luminaries as playwright William Inge. The Phoenix was planned as an “art theater”/repertory company that would be freed from the restrictions, both artistic and economic, of the Broadway stage.

The theater opened in December 1953. Over the course of eight full seasons in this house, the Phoenix Theater presented an impressive array of American and European theatrical talent, from both the stage and motion pictures. Despite the company’s emphasis on established actors, it also formed a reputation for assisting the careers of talented newcomers.

Productions by LGBT creators and with LGBT performers at the Phoenix included:

- The Golden Apple (1954), by and with lyrics by John Latouche

- Coriolanus (1954), with actor Will Geer

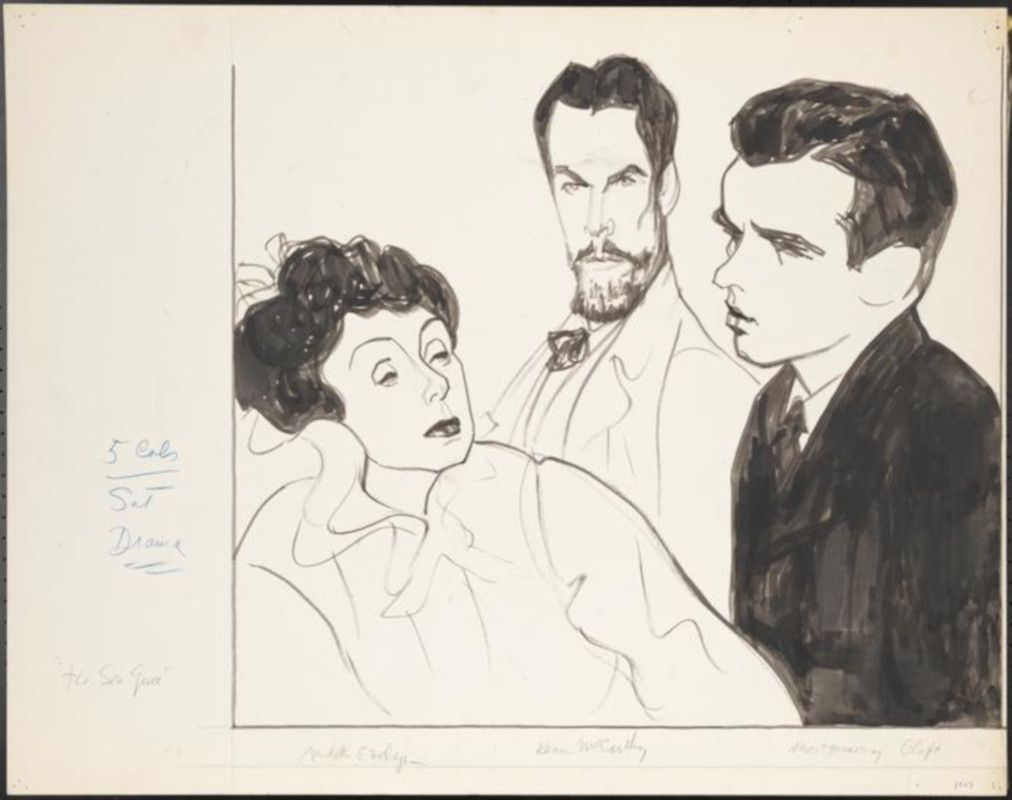

- The Seagull (1954), adapted by Montgomery Clift and others, directed by Norris Houghton, and with actors Clift and Will Geer

- Sandhog (1954), with actor Jack Cassidy

- The Doctor’s Dilemma (1955), with actor Roddy McDowall

- The Carefree Tree (1955), with actor Farley Granger

- A Month in the Country (1956), book adapted by Emlyn Williams and directed by Michael Redgrave

- The Littlest Revue (1956), conceived by Ben Bagley, with actor Joel Grey

- Diary of a Scoundrel (1956), with actor Roddy McDowall

- Measure for Measure (1957), with scenic and costume design by Rouben Ter-Arutunian and production and lighting design by Jean Rosenthal, and with actor Richard Easton

- Taming of the Shrew (1957), with scenic design by Rouben Ter-Arutunian and additional décor and lighting design by Jean Rosenthal, and with actor Richard Easton

- The Duchess of Malfi (1957), with music by Lee Hoiby, festival staging by Rouben Ter-Arutunian, and production and lighting design by Jean Rosenthal, and with actors Hurd Hatfield and Richard Easton

- Mary Stuart (1957), with actor Eva Le Gallienne

- Makropoulos Secret (1957), with scenic design by Norris Houghton and lighting design by Tharon Musser

- The Chairs and The Lesson (1958), directed by Tony Richardson, with lighting design by Tharon Musser

- The Infernal Machine (1958), by Jean Cocteau, with lighting design by Tharon Musser

- Two Gentlemen of Verona (1958), with actor Roberta Maxwell

- The Family Reunion (1958), with scenic design by Norris Houghton

- The Beaux Stratagem (1959), with lighting design by Tharon Musser

- Once Upon a Mattress (1959), co-authored and lyrics by Marshall Barer, and with lighting design by Tharon Musser

- Peer Gynt (1960), with lighting design by Tharon Musser

- Henry IV (1960), with lighting design by Jean Rosenthal

- She Stoops to Conquer (1960), with music and songs composed by Lee Hoiby

Later in this building, as the Entermedia Theater, was the original production of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1978; transferred to the 46th Street Theater), directed by Peter Masterson and Tommy Tune, with musical numbers staged by Tune, and Thommie Walsh as associate choreographer.

See Peter Hujar Residence & Studio / David Wojnarowicz Residence & Studio for more information on this site’s LGBT history.

Landmark Designations for LGBT Significance

In 1993, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater a New York City Landmark and Interior Landmark. While the site was not designated specifically for LGBT significance, it was the second in the history of the LPC (established in 1965) to include an LGBT mention in the accompanying designation report. It was the first report to include the word “gay” in reference to three prominent residents. The report’s author, Jay Shockley, who was then in the Research Department at the LPC, went on to co-found the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project in 2015. See the report in the “Read More” section below.

Entry by Jay Shockley, project director (March 2017; last revised November 2021).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Harrison G. Wiseman

- Year Built: 1925-26

Sources

Christopher D. Brazee, Gale Harris, and Jay Shockley, “150 Years of LGBT History,” New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (June 2014).

Daniel Hurewitz, Stepping Out: Nine Walks Through New York City’s Gay and Lesbian Past (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1997).

Internet Broadway Database.

Jack Lait and Lee Mortimer, U.S.A. Confidential (New York: Crown Publishers, 1952).

Jay Shockley, Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater Designation Report (New York: Landmarks Preservation Commission, 1993).

“Kew Woman Accused of Liquor Violation,” Long Island Star-Journal, December 22, 1950.

Lillian Faderman, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in 20th-Century America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991). [source of pull quote]

Lisa E. Davis, “Back in Buddy’s Day,” Xtra, February 28, 2006, bit.ly/31d67tX.

Lisa E. Davis, “Drag Kings of Village Nightlife: Before and Way Before Stonewall,” Drag Kings of Village Nightlife: Before and Way Before, bit.ly/3rj2az3.

Michael Seligman and Jessica Bendinger, podcast, Mob Queens (2019), bit.ly/3o3MihN.

New York State Court of Appeals, Lenore F. Moore, Inc. v. O’Connell, et al. (New York State Liquor Authority), June 19, 1951.

New York Supreme Court, 181 Restaurant Corp. v. O’Connell, et al. (New York State Liquor Authority), March 28 and April 11, 1951.

“Which-Sex-Is-Which Club Loses License,” New York Daily News, April 28, 1951.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?