Emma Goldman Residence & “Mother Earth” Office

overview

Anarchist leader and immigrant Emma Goldman was the first prominent figure and ally in the United States to publicly speak out in support of homosexual rights.

From 1903 to 1913, she lived on the sixth floor of this East Village tenement and, for several years beginning in c. 1906, had an office for her Mother Earth publication in the building next door.

History

In 1885, Emma Goldman (1869-1940) fled her native Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire) for the United States, eventually marrying in Rochester, New York. After several prominent anarchists were convicted of murder for the 1886 bombing of a labor demonstration (later known as the Haymarket Riot) in Chicago, Goldman was one of many who believed they were wrongfully accused and became inspired to learn more about anarchism. Despite being an atheist, her Jewish roots and the anti-Semitism she faced also made her keenly aware of discrimination and oppression. In 1889, she left her husband and moved to New York City.

From 1903 to 1913, she lived in a sixth-floor apartment in the tenement building at 208 East 13th Street, then considered part of the Lower East Side. A gifted speaker, she was famous for her support of anarchist causes, such as freedom of expression, women’s equality, birth control, sexual freedom, and workers’ rights. She also took the unpopular stance, even within the anarchist community, of championing the rights of homosexuals and those who would identify today as bisexual and transgender. Recalled pioneering German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, “[Goldman] was the first and only woman, indeed the first and only American, to take up the defense of homosexual love before the general public.” She condemned the persecution of Oscar Wilde, who had been jailed for “gross indecency” in England in the 1890s.

It is a tragedy, I feel, that people of a different sexual type are caught in a world which shows so little understanding for homosexuals and is so crassly indifferent to the various gradations and variations of gender and their great significance in life.

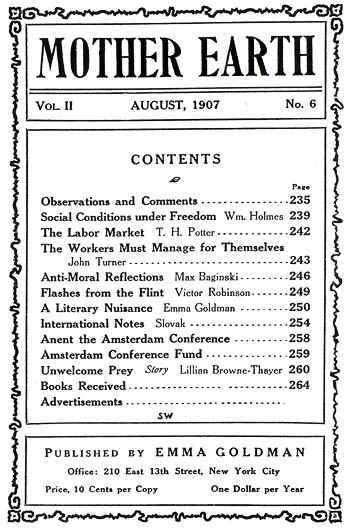

Goldman incorporated ideas from the 19th-century writings of European sexologists, such as Hirschfeld, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, and Havelock Ellis, into some of her lectures, which reached as many as 75,000 people annually. She has therefore been credited for making substantial contributions to homosexual visibility, particularly in the 1910s. Her monthly magazine Mother Earth, which she founded in 1906 and for several years ran from an office in the neighboring tenement at 210 East 13th Street, also included important articles on the subject (the publication ran until 1917, when it was banned by the federal government). At the same time, historians have noted that she was susceptible to stereotyping and being critical of gay men and lesbians. Some further theorize that her views on lesbianism may have been partially defensive since her untraditional femininity and nonconformist lifestyle were constantly scrutinized by the press.

In 1912 and 1913, Goldman corresponded with Almeda Sperry (1879-1957), a bisexual woman whose letters, writes LGBT historian Jonathan Ned Katz, “suggest that some kind of active sexual relationship did occur between the two women.” While Sperry’s feelings were much more passionate and unambiguous, Goldman (who had much stronger feelings for men) saved the letters and later returned them to Sperry. Historians have debated Goldman’s sexuality, with some arguing that the letters provide rare known evidence that it may have been more fluid.

After leaving the East 13th Street address, Goldman actively opposed World War I, which ultimately led to her deportation in 1919.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (May 2018).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Charles Rentz (both buildings)

- Year Built: 1901 (both buildings)

Sources

Clare Hemmings, Considering Emma Goldman: Feminist Political Ambivalence and the Imaginative Archive (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).

Doug Ireland, “Sexual Liberation, Human Freedom,” New Politics, Winter 2009, via bit.ly/2LlZb1p.

Emma Goldman,” Jewish Women Archive (accessed May 21, 2018), bit.ly/2jDEZL6. [source of pull quote]

The Emma Goldman Papers,” University of California-Berkeley Library, bit.ly/2rZ3ojD.

Jonathan Ned Katz, “Almeda Sperry to Emma Goldman: 1912,” Out History, bit.ly/2J06QUE. [source of Katz quote]

Lillian Faderman, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth Century America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 34.

Terence S. Kissack, Free Comrades: Anarchism and Homosexuality in the United States, 1895-1917 (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2008).

Read More

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?