Igal Roodenko Residence / Bayard Rustin Residence

overview

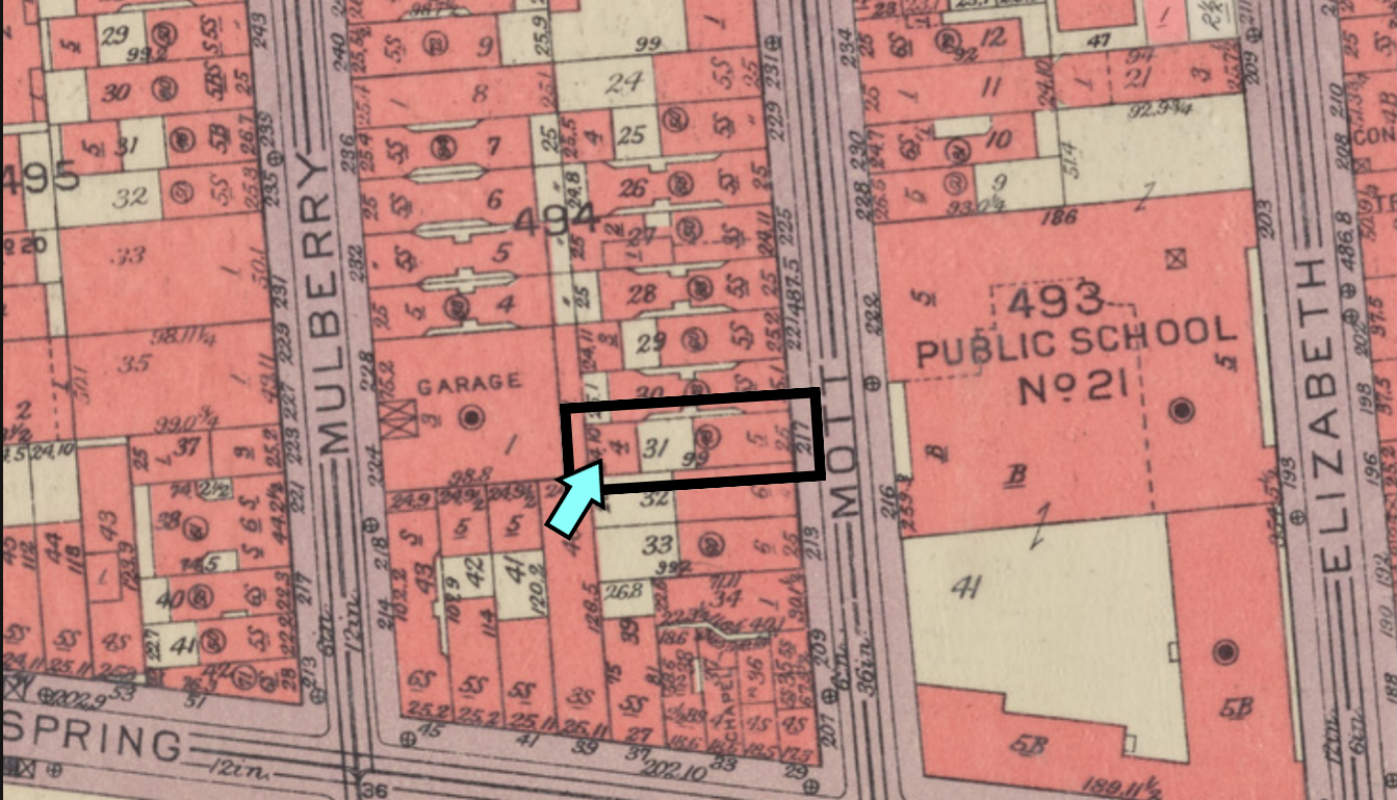

Behind this tenement building is another building at the back of the lot that was the home of civil rights activists, conscientious objectors, and pacifists Igal Roodenko, from 1947 to at least 1972, and Bayard Rustin, from 1947 to 1954.

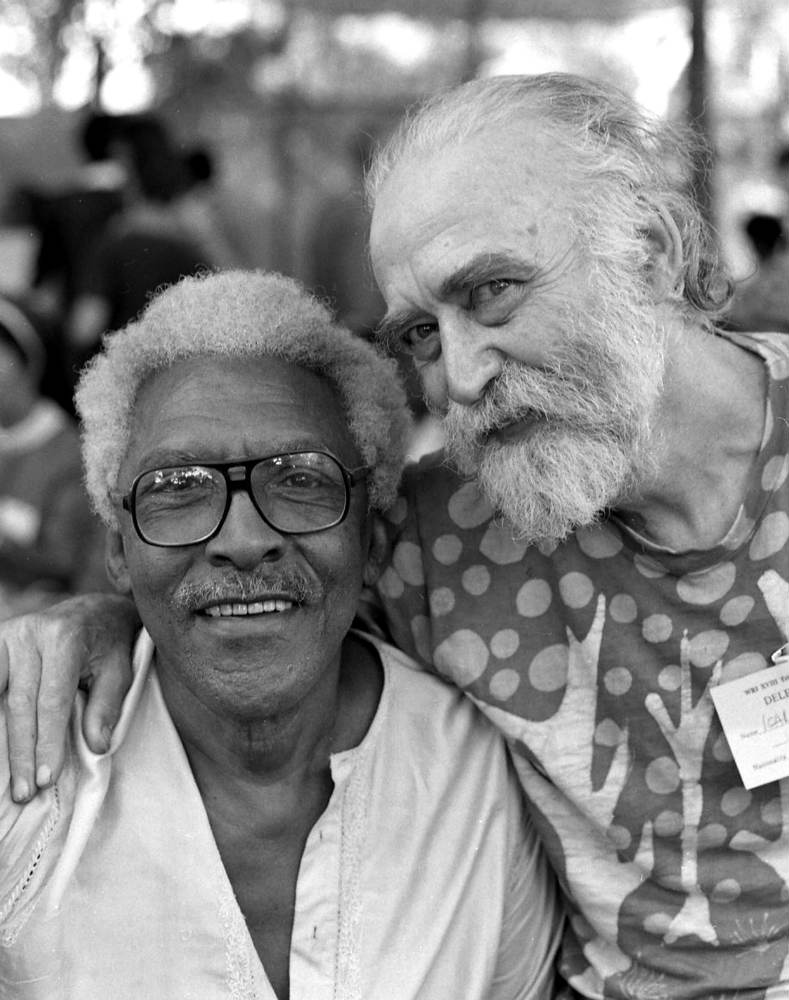

Living in separate apartments, both gay men, one Jewish and the other African American, took part in the influential “Journey of Reconciliation” in 1947 and contributed to other civil rights causes and anti-war campaigns during their time on Mott Street.

History

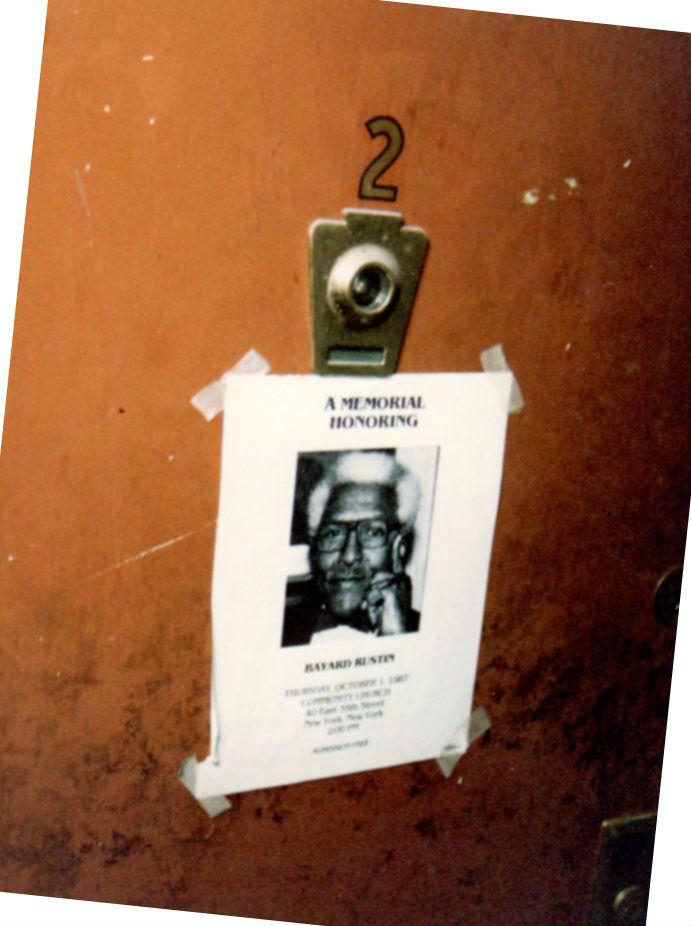

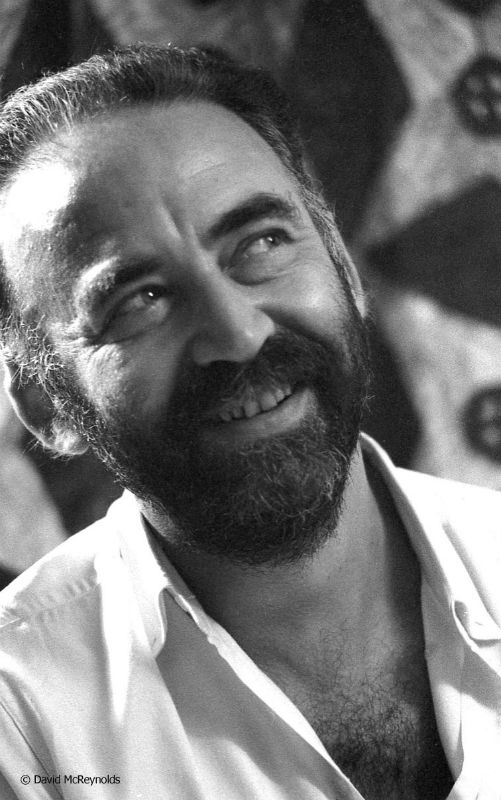

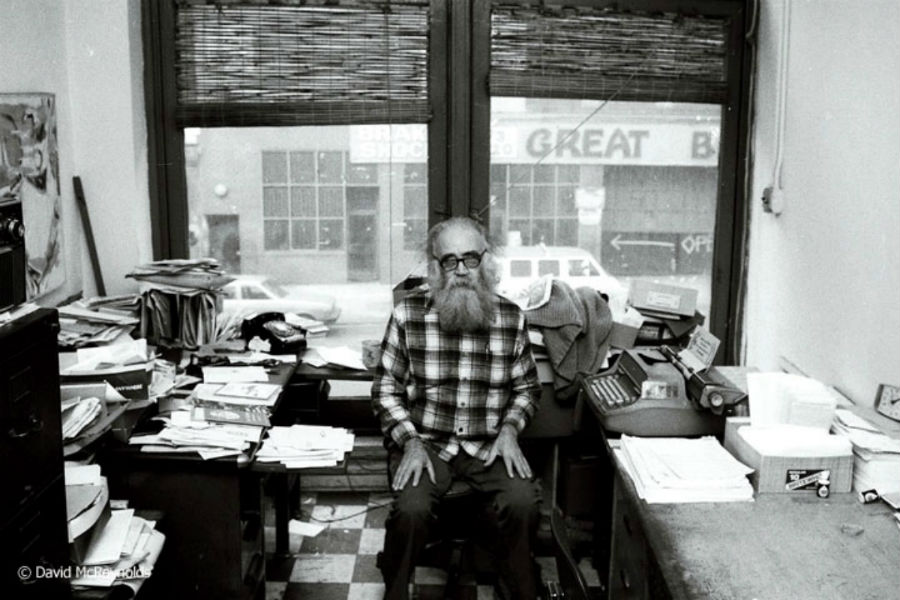

From the 1940s to the 1970s, a commune of artists, radical pacifists, conscientious objectors, and activists lived in a building behind the tenement building at 217 Mott Street on the western edge of the Lower East Side. Two notable gay residents were early civil rights activists, conscientious objectors, and pacifists Igal Roodenko (1917-1991) and Bayard Rustin (1912-1987). Roodenko, a New York City-born Jewish printer by trade, lived on Mott Street from 1947 to at least 1972. Rustin, who would later become Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s chief adviser, resided in apartment 2, on the floor below Roodenko, from 1947 to 1954. The immediate area was home to many young radical thinkers who provided each other with an important sense of community in the post-World War II, anti-Communist years, when dissenters and “outsiders” of any kind attracted suspicion.

Rustin and Roodenko, along with a set of young married couples with ties to the left, spent evenings together eating cheaply, attending concerts, and talking about the political causes that consumed them.

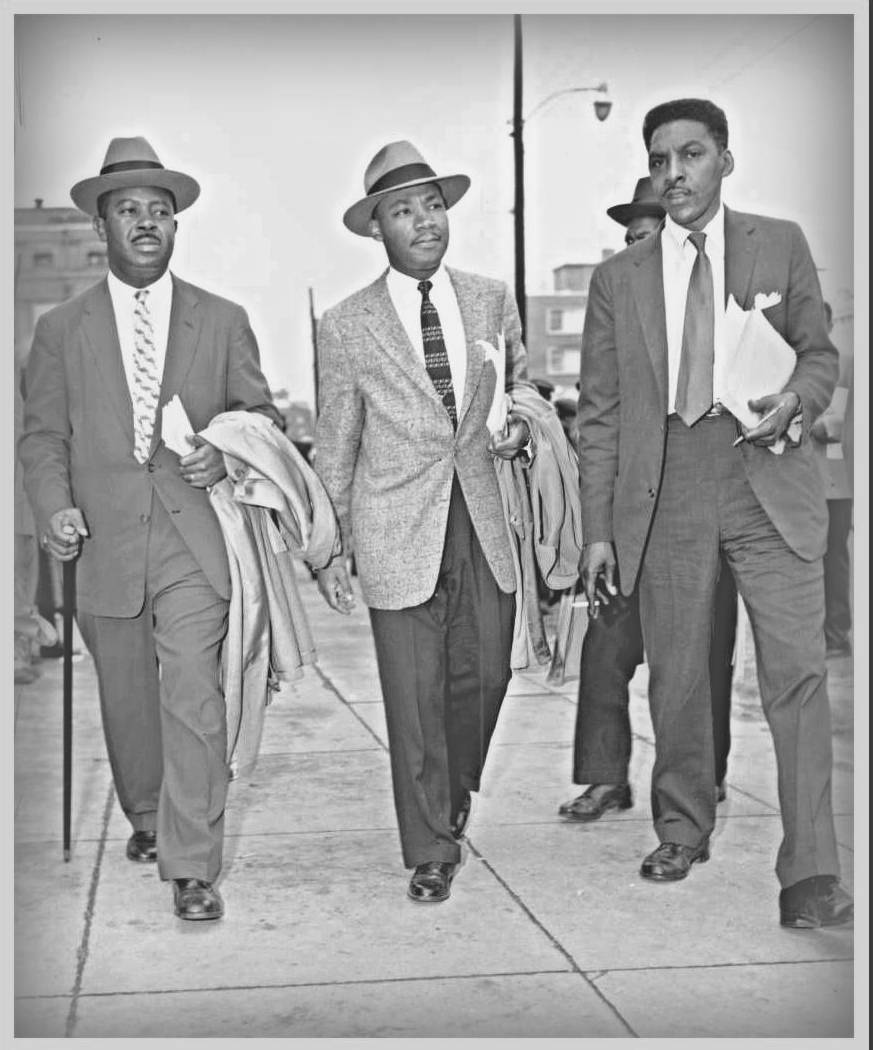

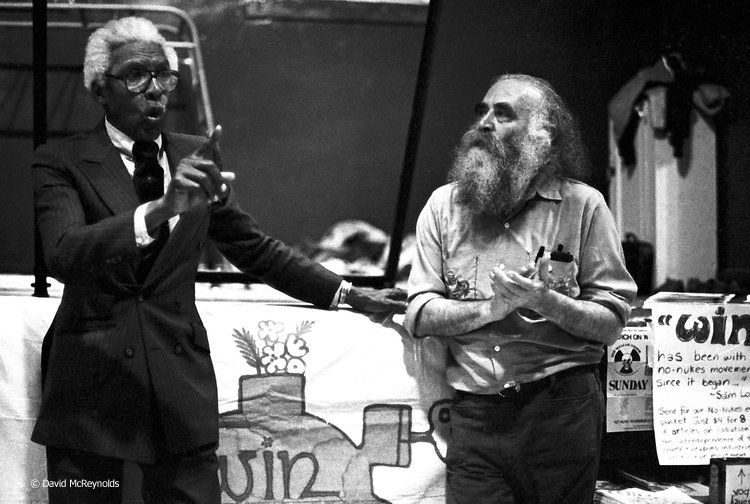

During their association with Mott Street, the two men were members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), an interracial group that evolved from the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) in 1942. CORE’s “Journey of Reconciliation” in 1947 sent sixteen Black and white men — including Rustin and Roodenko — to the upper South to test the enforcement of a 1946 Supreme Court decision that struck down racial segregation in interstate bus travel, which southern states refused to enforce. Violating the region’s segregated seating laws by either sitting next to each other on buses or having Black men sit at the front and white men at the back, Rustin, Roodenko, and several others were arrested and served time on chain gangs (in June 2022, their convictions were vacated and dismissed). While not considered a success, the event demonstrated the value of nonviolent direct action, which would become a hallmark of the civil rights movement, and inspired the Freedom Rides of the 1960s. It also illustrates the early involvement of LGBT people in the Black civil rights struggle.

During World War II, Roodenko was a conscientious objector; as a result, he eventually served time in a federal penitentiary from April 1945 to December 1946, the period just before he moved to Mott Street. Following the Journey of Reconciliation, he wrote an exposé in The New York Post about his time on a North Carolina chain gang, which played a significant role in abolishing the chain gang system in that state. A member of the War Resisters League (WRL), he served on its executive board from 1947 to 1977, as its vice chair from 1958 to 1968, and as its chair from 1968 to 1972 (founded in 1923, the WRL is the nation’s oldest secular pacifist organization). Roodenko was also a leader in the anti-Vietnam War movement and led the first demonstration against the United States military’s involvement. The WRL awarded him its annual Peace Award in 1979. Roodenko served on the boards of the A.J. Must Memorial Institute and the Consortium in Peace Research and Development. At the time of his death, he was active with Black and White Men Together (later known as Men of All Colors Together), a group dedicated to addressing racism in the LGBT community.

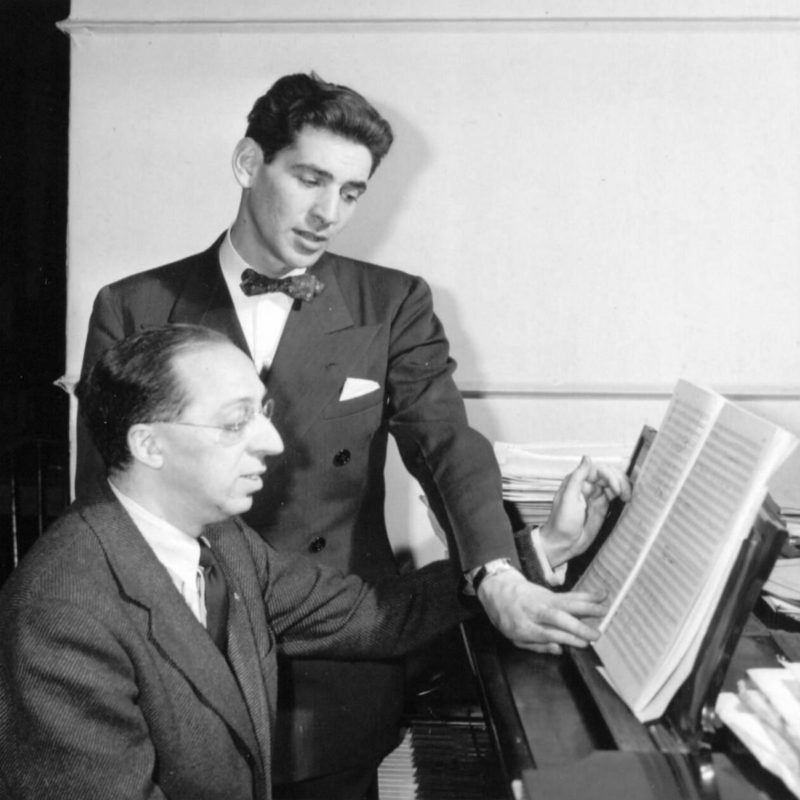

Rustin also served jail time for refusing to register for the draft during World War II. In 1948, he took part in a successful campaign to end segregation in the military, with one of the largest demonstrations taking place in Harlem. Five years later, he was arrested on a morals charge (for a homosexual act) in California, which publicly outed him as a gay man. Returning to New York, Rustin was forced to resign from the Fellowship of Reconciliation and, in subsequent years, his homosexuality was used against him. His resignation from the War Resisters League, however, was refused and he was given a job as a program director. After leaving the Mott Street address, he eventually settled in an apartment in Penn South, where he would live for the rest of his life.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (May 2018; last revised August 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown

- Year Built: 1873

Sources

Igal Roodenko Papers, 1935-1991,” Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

Jervis Anderson, Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen: A Biography (New York: HarperCollins, 1997).

John D’Emilio, Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin (New York: Free Press, 2003). [source of pull quote]

Gale Harris, LGBT Research File, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2014.

Igal Roodenko, 74; Led Anti-War Group,” The New York Times, May 1, 1991.

Mark Meinke and Kathleen LaFrank, “Bayard Rustin Residence,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Waterford, NY: New York State Historic Preservation Office, March 8, 2016).

Oral History Interview with Igal Roodenko, April 11, 1974,” Civil Rights Digital Library, bit.ly/2rJ6szc.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?