James Baldwin Residence

overview

Literary icon and civil rights activist James Baldwin used this Upper West Side remodeled rowhouse as his New York City residence from 1965 until his death in 1987.

Although he generally eschewed labels and did not self-identify as gay, Baldwin wrote several novels that featured gay and bisexual characters and spoke openly about same-sex relationships and LGBT issues.

Through the efforts of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, this site was listed on the New York State Register of Historic Places and the National Register of Historic Places in 2019. The Project’s advocacy also led to the site’s designation as a New York City Landmark by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission that same year.

History

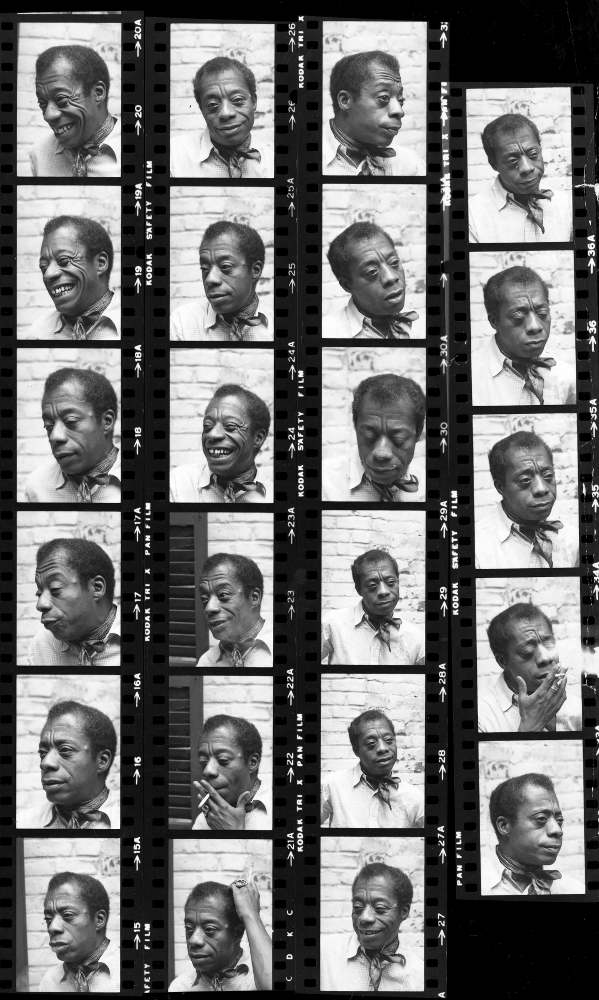

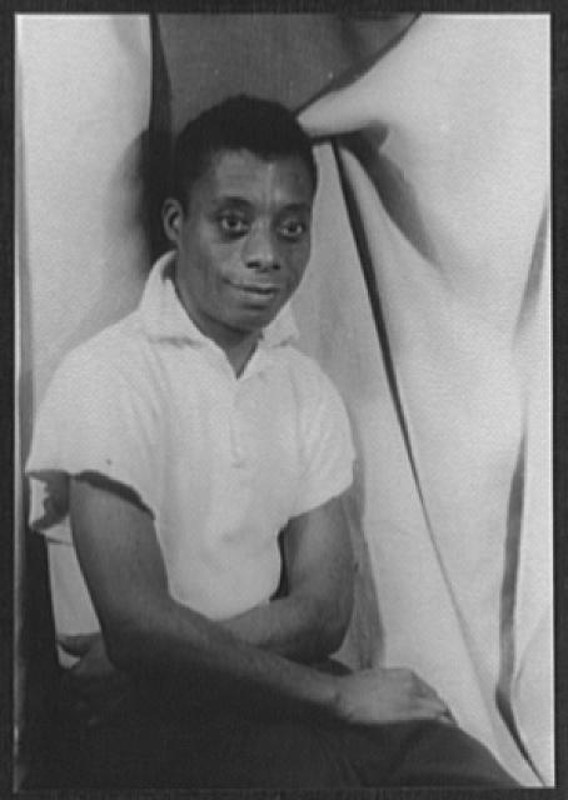

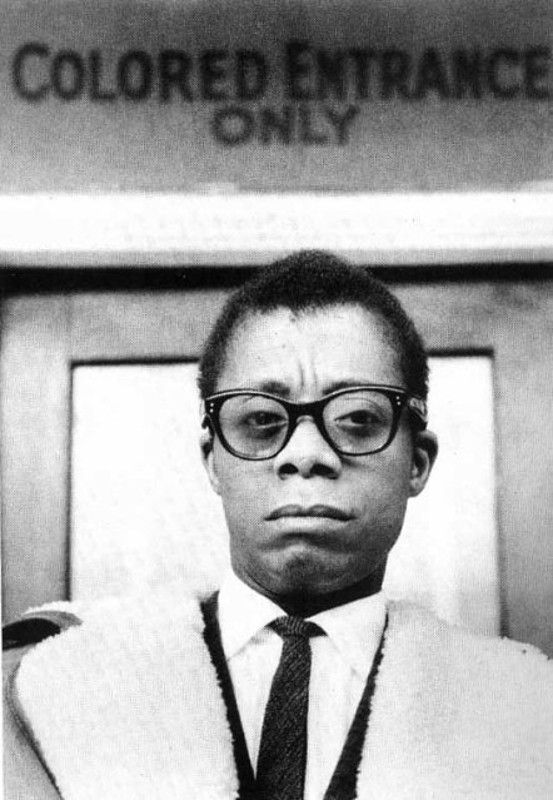

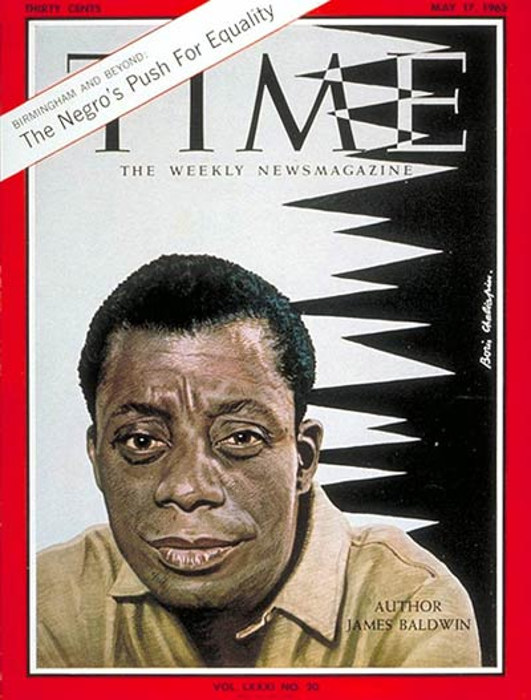

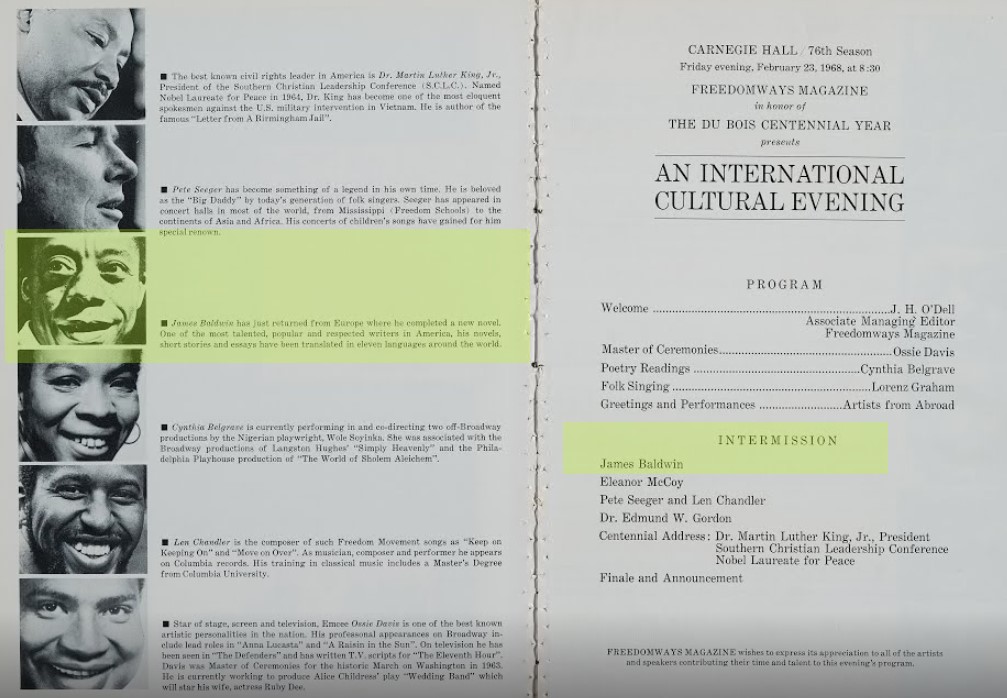

Through his writing, televised appearances, and public speaking here and abroad, author and civil rights activist James Baldwin (1924-1987) became a critical voice for the Black civil rights movement and brought attention to racial issues in the United States. He took part in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march, for example, and wrote about the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the sit-ins, and other civil rights events taking place in the South.

Baldwin’s experiences with racism in this country led him to live most of his adult life as a self-described “transatlantic commuter.” While he lived primarily in France, he often featured New York, including his native Harlem, in his work and resided in a number of apartments here. From 1958 to 1961, for example, he lived at 81 Horatio Street in Greenwich Village. In 1965, at the height of his fame, he moved into a remodeled rowhouse at 137 West 71st Street on the Upper West Side, which he used as his New York City residence until his death. He lived in the rear, ground-floor apartment, and his family, including his mother, sister, and her children, had apartments on the upper floors. The house was known as an important social hub for civil rights activists and Black literary figures, including the author Toni Morrison, who briefly lived here. Baldwin’s pioneering children’s book, Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood (1976) featured his niece and nephew and used the 71st Street house as inspiration, though the story was set in Harlem.

Considered the first major Black writer since the Harlem Renaissance to speak and write about same-sex relationships, Baldwin “pioneered fictional accounts of homosexuality and bisexuality in his fiction,” according to biographer Douglas Field. This began with his groundbreaking second novel, Giovanni’s Room, published in 1956. (He dedicated it to the Swiss painter Lucien Happersberger, whom Baldwin considered “the one true love story of my life.”) Baldwin’s influence reached many in the LGBT community, regardless of race, but also inspired a new generation of LGBT African-American writers, in particular. Gay or bisexual characters also featured in his novels Another Country (1962), which he worked on while living on Horatio Street, Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (1968), and Just Above My Head (1979). The latter two novels were published during his association with West 71st Street.

In a 1987 interview, drawing on his experience as both a Black man and a gay man, he addressed ongoing homophobia and noted that “People’s attitudes don’t change because the law changes.” He continued:

A man can fall in love with a man; a woman can fall in love with a woman. There’s nothing anybody can do about it. It’s not in the province of the law. It has nothing to do with the church. And if you lie about that, you lie about everything. And no one has a right to try to tell another human being whom he or she can or should love.

On June 5, 1982, Baldwin spoke on the topic, “Race, Racism, and the Gay Community” at a meeting of the New York chapter of Black and White Men Together (known since 1985 as Men of All Colors Together), held at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, an LGBT synagogue at Westbeth. While he generally eschewed labels and did not self-identify as gay, he was open about the fact that he had relationships with men and spoke openly about various LGBT issues. He first wrote about his own sexuality in his 1985 essay, “Here Be Dragons,” which was also published as “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood.”

In 1987, Baldwin died in France, but his funeral was held at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in Morningside Heights, Manhattan.

Landmark Designations for LGBT Significance

In June 2019, based on recommendations by the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the James Baldwin Residence a New York City Landmark. In September 2019, the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project’s nomination of the James Baldwin Residence to the National Register of Historic Places was approved by the National Park Service, following the site’s listing on the New York State Register of Historic Places in June 2019. The LPC’s designation report, the Project’s testimony, and the National Register nomination are available in the “Read More” section below.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (March 2017; last revised September 2019).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: H. Russell Kenyon

- Year Built: 1961 (remodeled)

Sources

Aisha Karefa-Smart, “Foreword: The Prodigal Son,” African American Review 46.4 (Winter 2013), 559.

Christopher D. Brazee, Gale Harris, and Jay Shockley, “150 Years of LGBT History,” New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2014.

Daniel Hurewitz, Stepping Out: Nine Walks Through New York City’s Gay and Lesbian Past (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1997).

David Leeming, James Baldwin: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1994).

Douglas Field, James Baldwin (Devon, UK: Northcote House Publishers, 2011). [source of Field quote, p. 48]

“James Baldwin (1987),” Mavis on 4, Channel Four, March 23, 1987. [source of pull quote]

Paula Martinac, The Queerest Places: A National Guide to Gay and Lesbian Historic Sites (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1997).

Richard Goldstein, “Go the Way Your Blood Beats: An Interview with James Baldwin,” The Village Voice, June 26, 1984, 13-14.

W.J. Weatherby, James Baldwin: Artist on Fire (New York: Dutton Adult, 1989).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?