Mario Montez Residence

overview

A key figure in New York’s underground film and theater scene, Puerto Rican-born Mario Montez starred in over 20 movies and was one of Andy Warhol’s superstars.

From 1962 to 1969, Montez lived in an apartment in this Lower East Side building, where he met many underground artists.

History

Born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, Mario Montez (1935-2013; born René Rivera) was one of the central drag performers of the New York underground film and theater scene in the 1960s and early 1970s. In 1944, his family migrated to New York and lived in an apartment at 211 East 111th Street in El Barrio. After graduating from the New York School of Printing (now the High School of Graphic Communication Arts), Montez worked as a clerk and took free ballet courses for low-income residents. Through this program, he met model Reese Haire, who introduced him to filmmaker Jack Smith in the early 1960s.

This led to a short-lived relationship but also a lasting collaboration between the two, starting with Smith’s Flaming Creatures in 1963, the controversial film shut down by police during a screening in May 1964. During filming in the summer of 1962, Montez moved into a Lower East Side apartment at 56 Ludlow Street, where Smith and other underground artists, such as Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, and Lou Reed, lived. For Flaming Creatures, Smith suggested the name Dolores Flores for Montez’s character; the name Mario Montez first appeared in movie credits in Smith’s Normal Love (1963-65) and Ron Rice’s Chumlum (1964). The artist adopted Mario Montez as a name in honor of Dominican actress María Montez, whom he and Smith adored. Smith introduced Montez to Andy Warhol, and Montez then became one of Warhol’s superstars, starring as Jean Harlow in Harlot (1964), the two Mario Banana short films (1964), and The Chelsea Girls (1966; partially filmed at the Chelsea Hotel), among many others.

Mario is very, very good, and no one moves all the muscles in his face the way Mario does. He really knows what to do in front of a camera. He has an instinct for it.

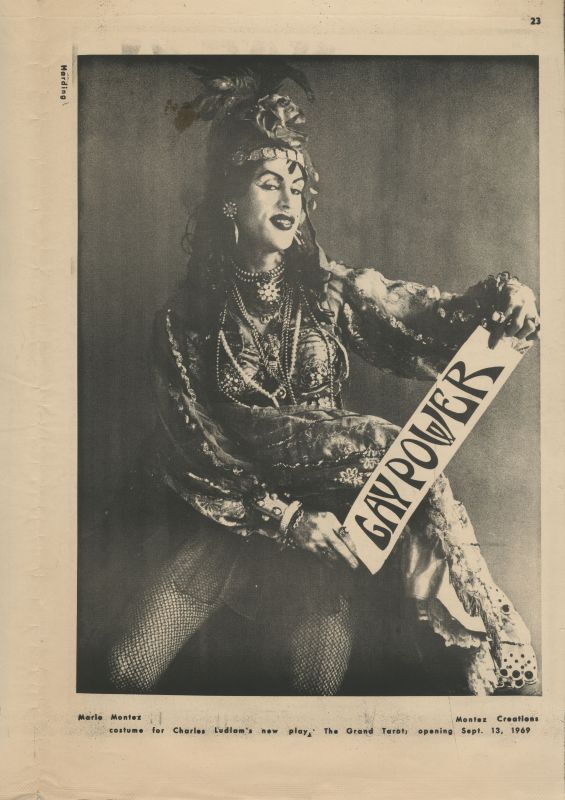

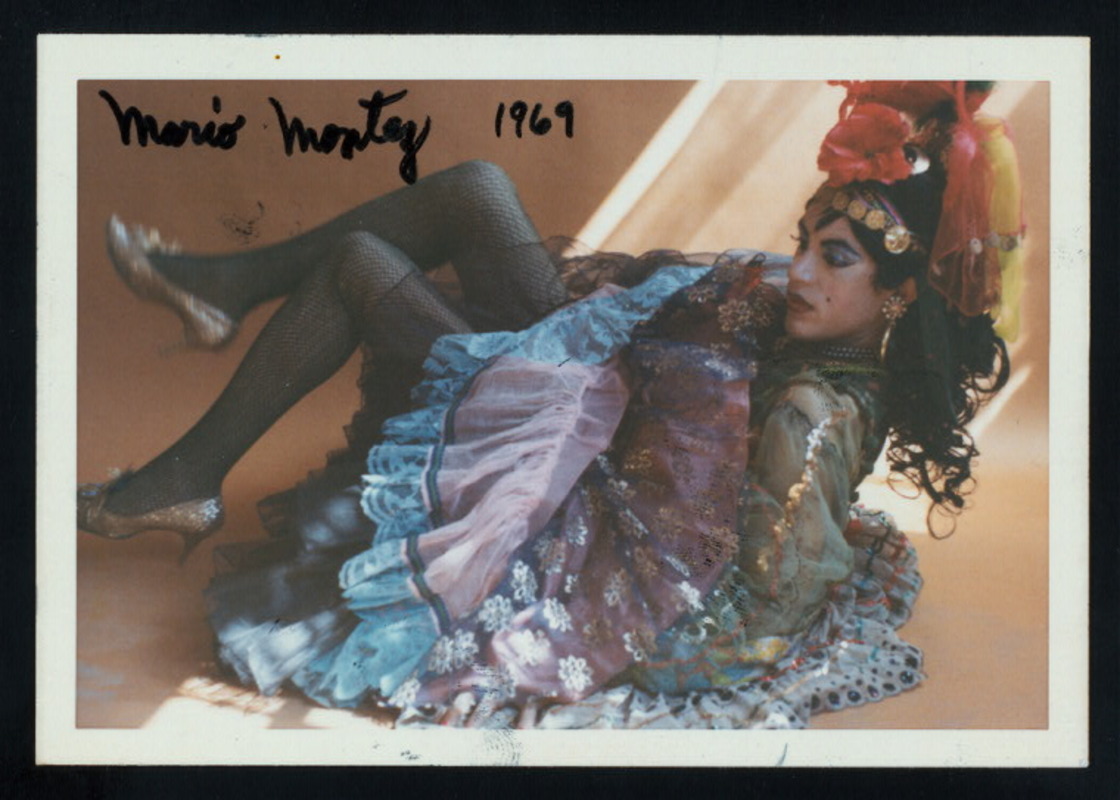

Montez lived at 56 Ludlow Street until 1969. While there, Montez kept collaborating with Smith and other filmmakers. Notably, he collaborated with Puerto Rican avant-garde and political filmmaker José Rodríguez-Soltero by paying homage to Mexican actress Lupe Vélez in his film Life, Death and Assumption of Lupe Vélez (1966), which was financially supported by Warhol. As a collaborator, Charles Ludlam described the film as a “Puerto Rican epic” (despite the only Puerto Rican elements of the movie being Montez and Rodríguez-Soltero). Montez considered this film one of his best because of Rodríguez-Soltero’s filming process.

He was one of the best directors I’ve had. I worked very hard. At times I felt like I was in Hollywood because I had so many things to do—four location shots—walking in the street in costume; I was scared about that, but it had to be done, and since I was wearing the red wig, I looked like his sister.

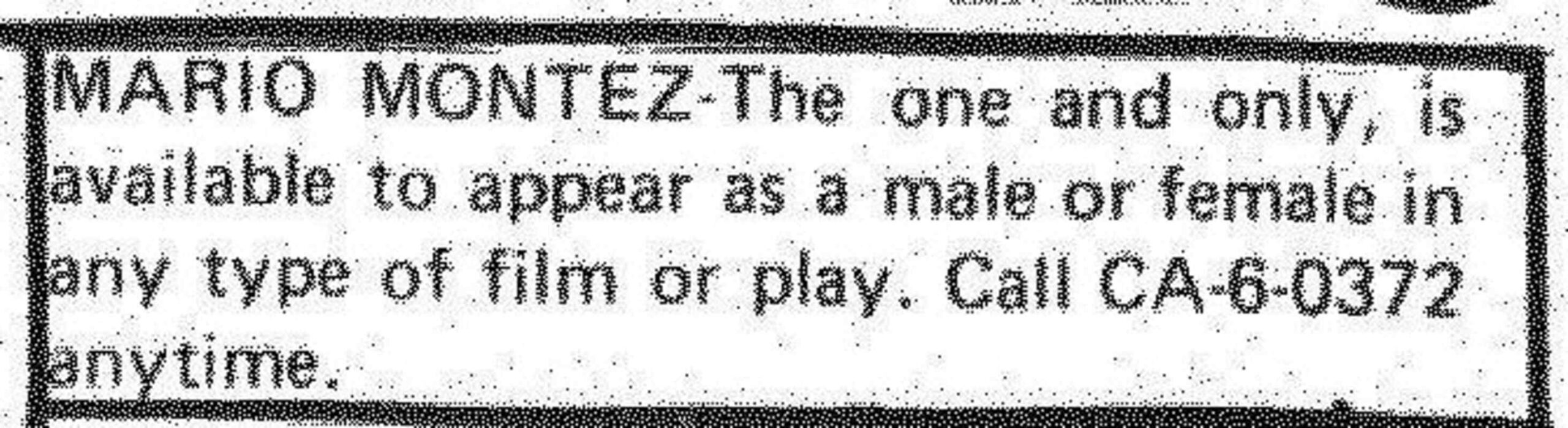

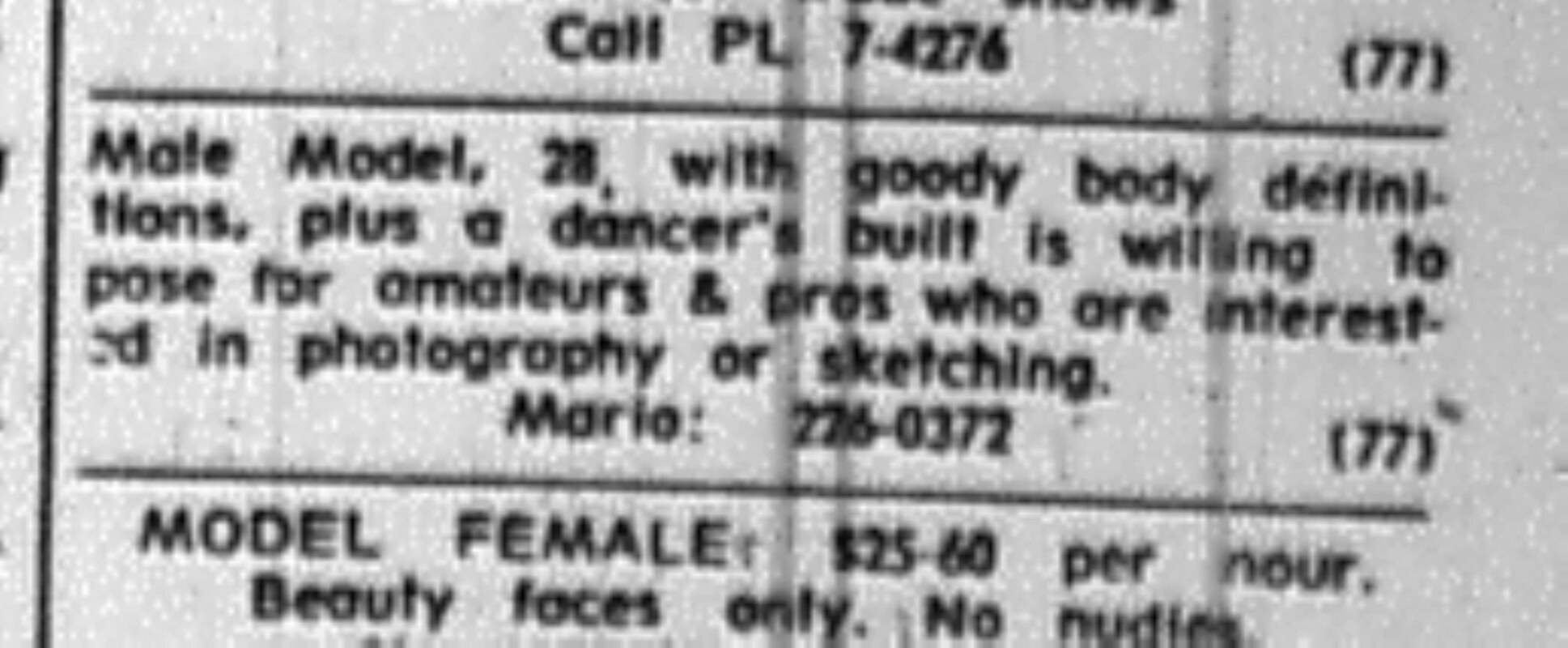

Before the filming of Rodríguez-Soltero’s movie, Montez created his own costume company, Montez Creations, through which he made the costumes for Life, Death, and Assumption of Lupe Vélez and some of the productions for Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company, with whom he also collaborated as an actor in the late 1960s until the mid-1970s. By 1969, he calculated that he spent $50 a year on costumes and $20 on make-up, mostly buying at thrift shops and creating his items. He also ran ads in The Village Voice to gain work as a male model, going by the name Mario Rivera. In the early 1970s, Montez appeared in Off-Off-Broadway productions such as Vain Victory (Jackie Curtis, 1971) at La MaMa and In Search of the Cobra Jewels (Harvey Fierstein, 1972).

In January 1977, Montez relocated to Orlando, Florida, retiring from the stage after Ludlam’s Caprice (1976). Following almost 30 years out of the spotlight, he resurfaced in 2006 for a documentary on Jack Smith and began participating in forums and festivals in Berlin and New York. A year before his death, Montez received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Teddy Awards at the Berlin Film Festival in 2012.

Entry by Andrés Santana-Miranda, project consultant (December 2024).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Frederick Renth

- Year Built: 1885

Sources

Frank Keating, “… and Lace,” Queen’s Quarterly 1, no. 3 (1969): 16-19, 44.

Gary McColgen, “The Superstar: An Interview with Mario Montez,” Film Culture, no. 45 (Summer 1967): 17-20. [source of second pull quote].

Hélio Oiticica, “Héliotape with Mario Montez (1971),” Criticism 56, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 379-404.

John Gruen, “The Underground’s M.M. — Mario Montez,” New York/World Journal Tribune, January 22, 1967, 29, reprinted in Close-up (New York: Viking Press, 1968), 28-31. [source of first pull quote].

Juan A. Suárez, “Glitter and Queer Embodiment in 1960s and 1970s Experimental Film and Performance,” in Experimental Film and Queer Materiality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), 116-150.

Juan A. Suárez, “The Puerto Rican Lower East Side and the Queer Underground,” Grey Room, no. 32 (Summer 2008): 6-37.

Marc Siegel, “… for MM,” Criticism 56, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 361-374.

Marc Siegel, “How Not to Lose Track of Time: Remembering Mario Montez (1935-2013),” Texte zur Kunst 23, no. 92 (December 2013): 248-250.

Melissa Anderson, “The Return of Mario Montez, Warhol Legend,” The Village Voice, November 9, 2011. bit.ly/41osVUE.

Ronald Gregg, “Fashion, Thrift Stores and the Space of Pleasure in the 1960s Queer Underground Film,” in Birds of Paradise: Costume as Cinematic Spectacle, ed. Marketa Uhilrova (London: Koenig Books, 2013), 293-304.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?