Assotto Saint & Jan Holmgren Residence

overview

From 1981 until his death from AIDS-related complications in 1994, Assotto Saint lived in apartment 2D of this Chelsea building with his life partner, Jan Urban Holmgren.

As a Haitian-born American poet, playwright, editor, and activist, Saint increased the visibility of contemporary Black queerness, elucidated the Black immigrant experience during the AIDS crisis, and fought to make visible the disproportionate physical and cultural toll that the epidemic was having on Black gay men.

History

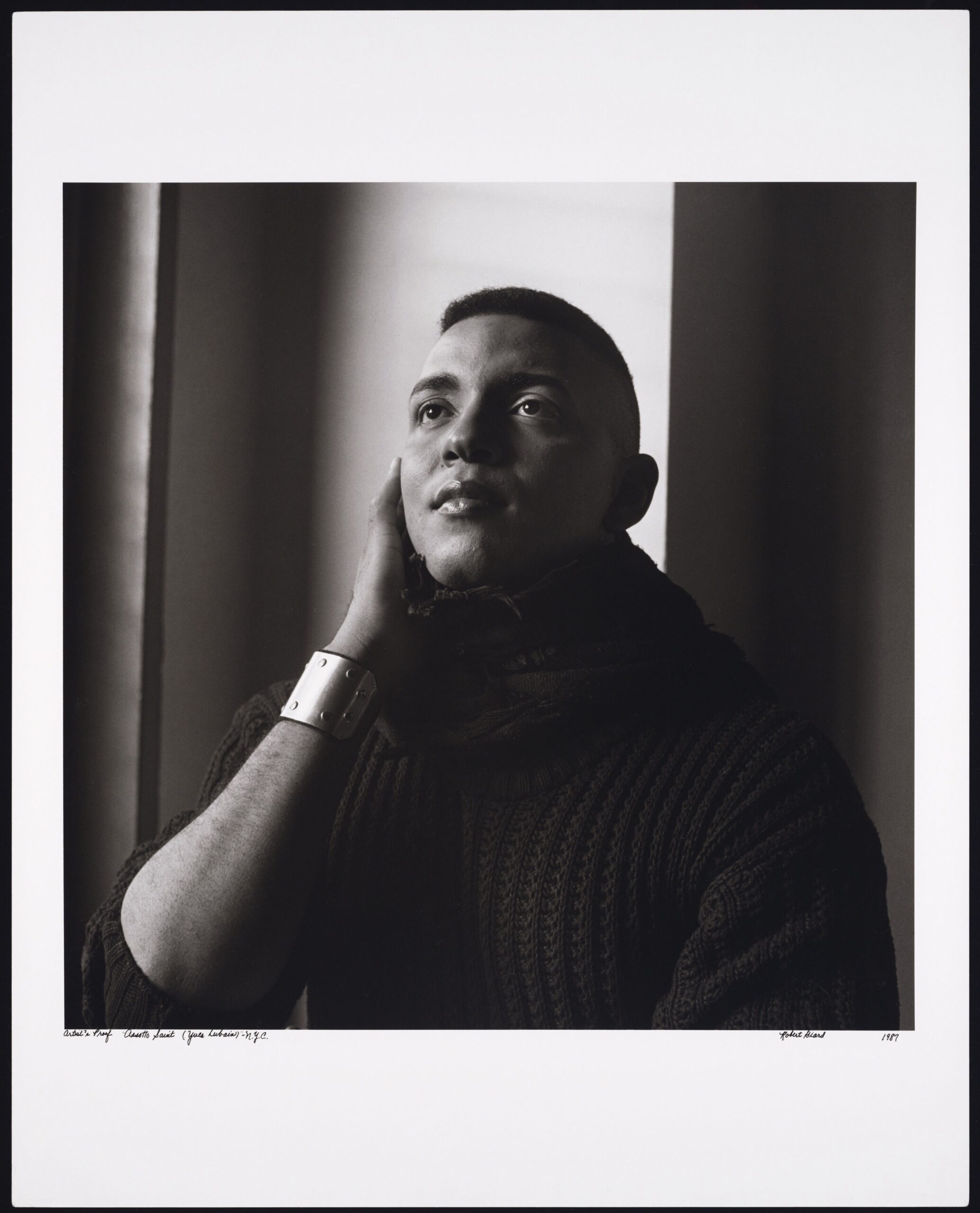

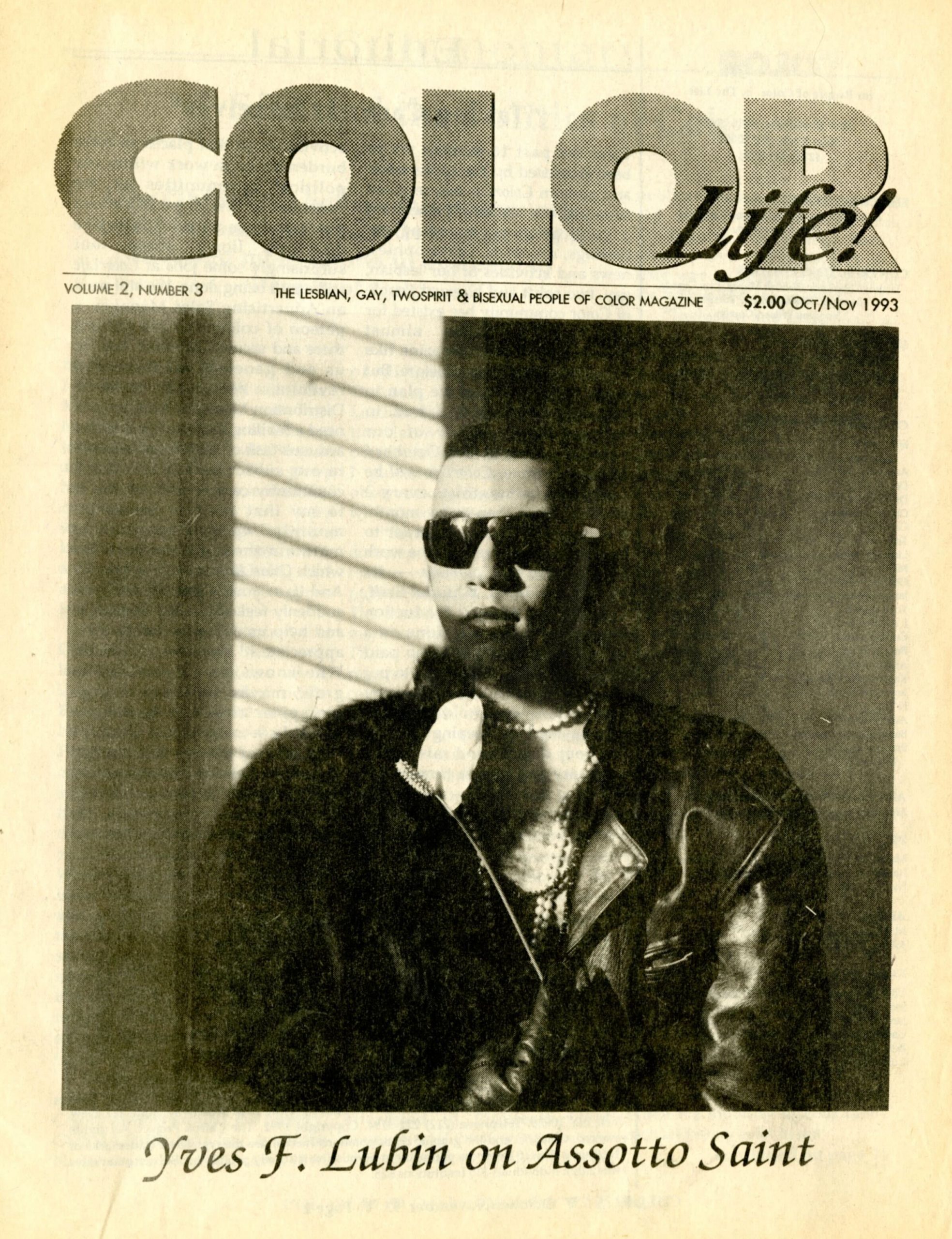

Born Yves François Lubin in Cap-Haïtien, Haiti, Assotto Saint (1957-1994) decided to immigrate to New York in 1970 after being “stunned” by the freedom of gender expression he encountered when visiting Coney Island with his mother, who lived in Queens. Saint moved into her apartment at 224-10 Jamaica Avenue in Queens Village and, after graduating from Jamaica High School, briefly attended a pre-med program at Queens College. Although he left to explore his artistic interests, dancing for Martha Graham from 1974 to 1980, Saint worked for the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation from 1978 until 1991.

Saint chose his “nom de guerre” when he began writing in 1980, selecting “Assotto” after the sacred asòto drum in Haitian Vodou (he initially spelled it with one “t” but added a second when his CD4 t-cell count dropped to nine following his AIDS diagnosis in 1991), and “Saint” after Haitian Revolution leader Toussaint Louverture.

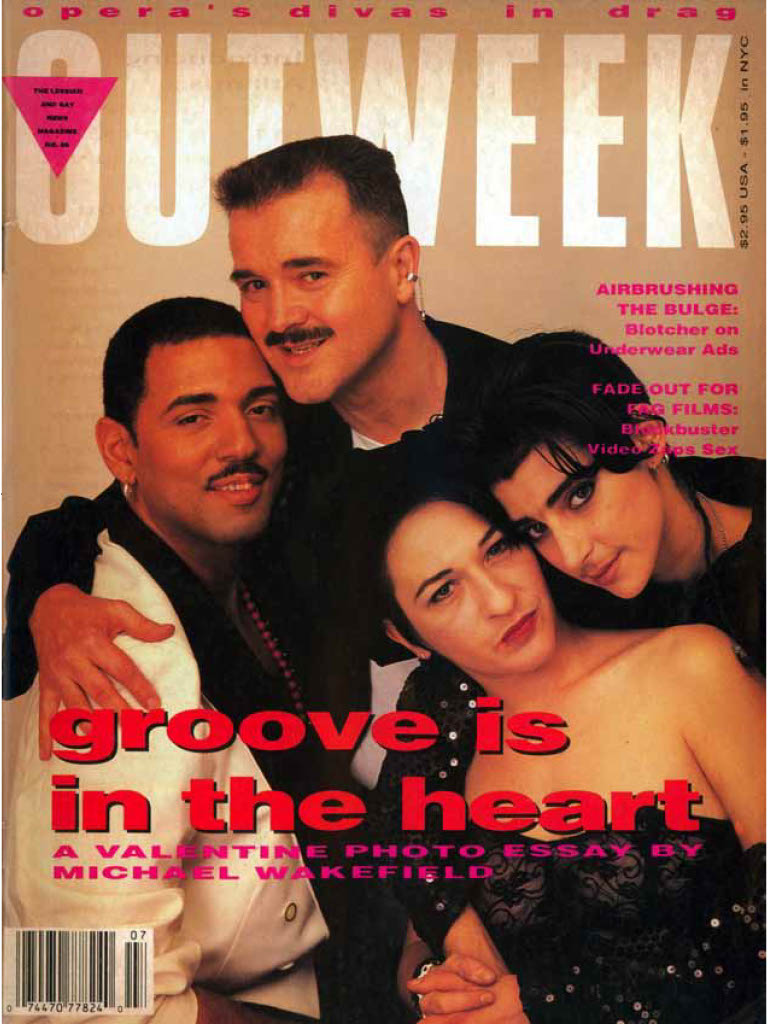

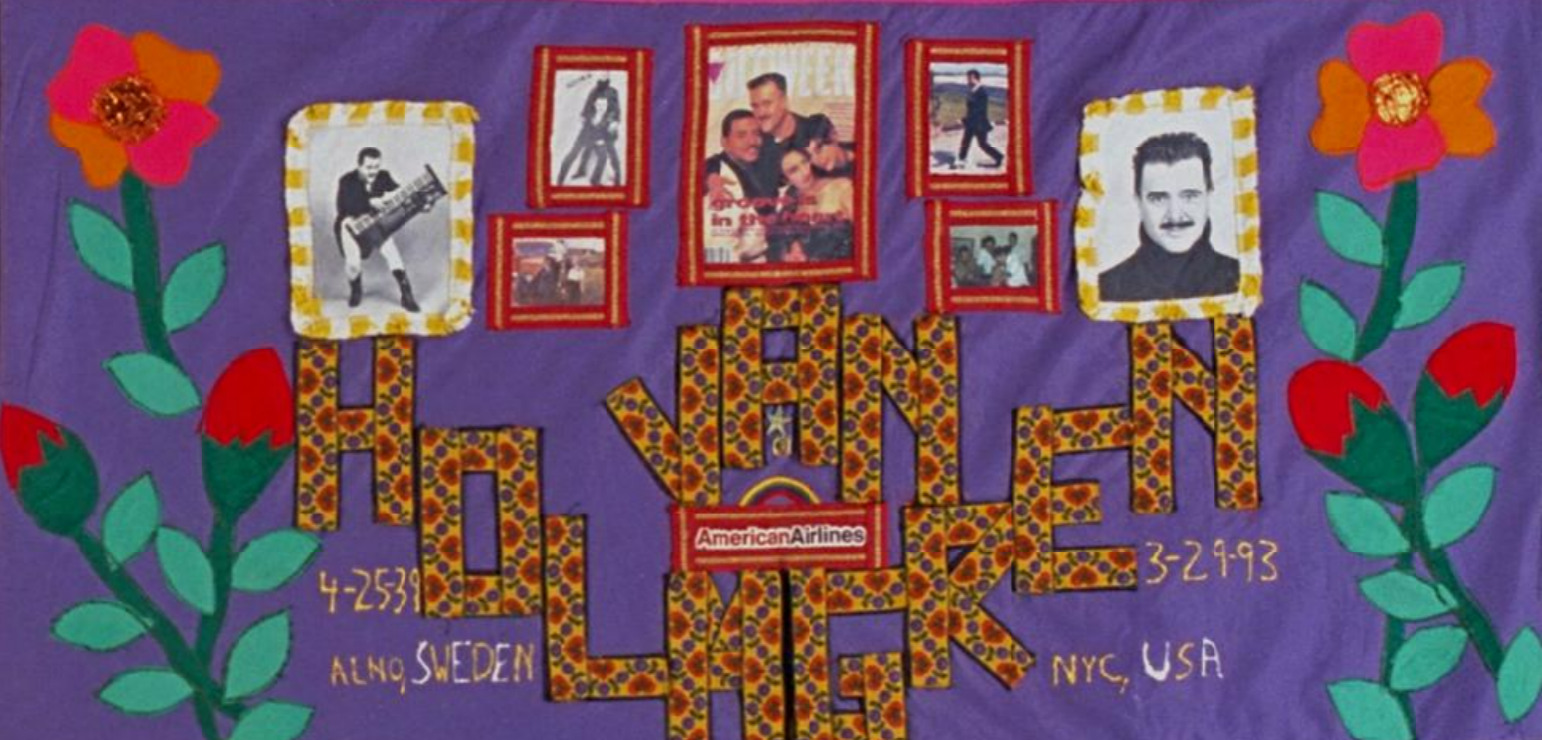

Later that year, Saint met and fell in love with Swedish-born flight attendant and musician Jan Urban Holmgren (1939-1993), who had lived in New York since 1965. They moved to 360 West 22nd Street in Chelsea in 1981, renting a second-floor apartment with a plant-filled terrace facing Ninth Avenue. They collaborated on various projects, including Xotika, a “rock-theater dance band” in which Saint (often in drag) and Holmgren performed songs like “Forever Gay” and “ACT UP” at Danceteria, Pyramid Club, La MaMa, and the NYC Pride March.

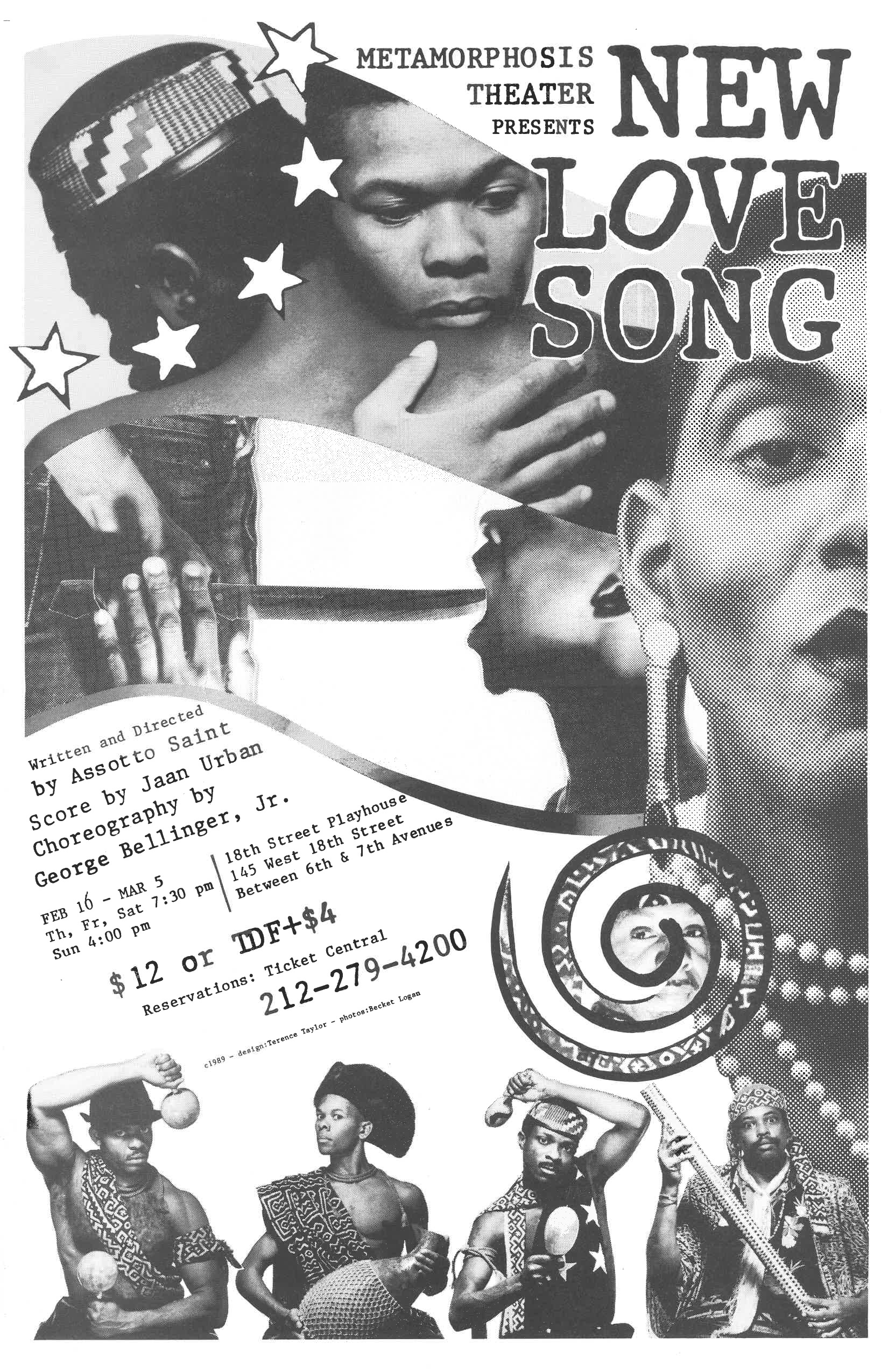

Saint also established Metamorphosis Theater to produce multimedia theater pieces—all scored by Holmgren—that were groundbreaking for their display of “Black gay men on stage being Black gay men,” says Allen Wright, an actor in Saint’s New Love Song (1989). The pieces brought attention to racism, xenophobia, and anti-effeminacy in the LGBT community, the fetishization and sexual assault of Black men, perceptions of interracial relationships, and the illusion of the American Dream.

My poems and plays are weapons and blessings that I use to liberate myself, to validate our realities as gay black men, and to elucidate the human struggle.

In these pieces, whether through dialogue, costumes, sets, or the projection of archival footage, Saint “inscribed the people and places around him,” scholar Jaime Shearn Coan indicates, “along with historical events and figures that connected to and influenced the present.” For example, in Risin’ To The Love We Need (1980), the protagonist, based on Black trans activist Marsha P. Johnson, discusses the civil rights movement’s influence on the Stonewall uprising and the Greenwich Village Waterfront as a site of both sexual liberation and racial violence.

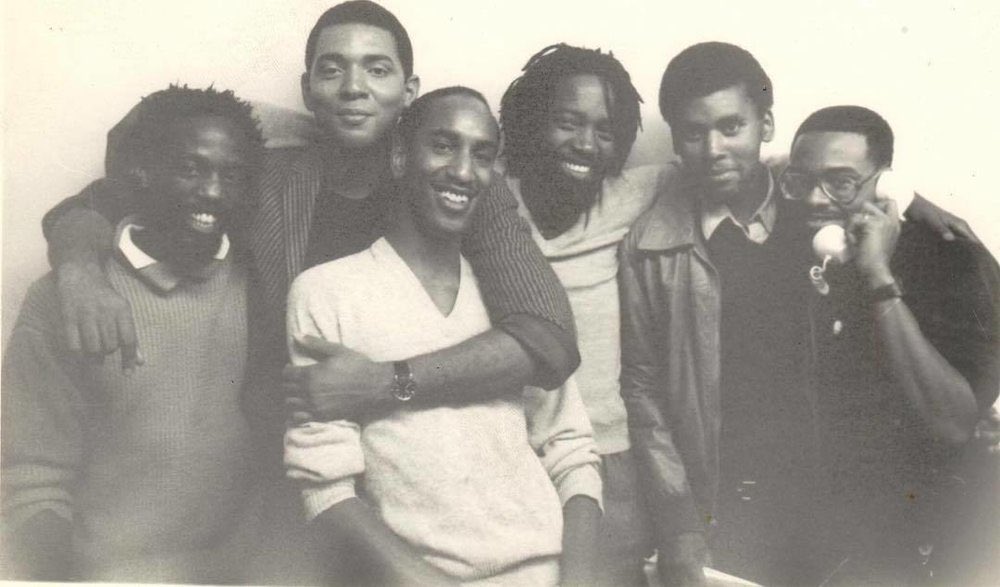

Active in the Blackheart Collective, Saint was also a founding member (and poetry editor of the first journal) of its successor, Other Countries, both of which provided a platform for publishing his works and opportunities to perform them, often at the LGBT Community Center. Notably, portions of Risin’ were published in Blackheart’s first journal, Yemonja (1982), and Joseph Beam’s In the Life (1986), the earliest anthology of Black gay writing.

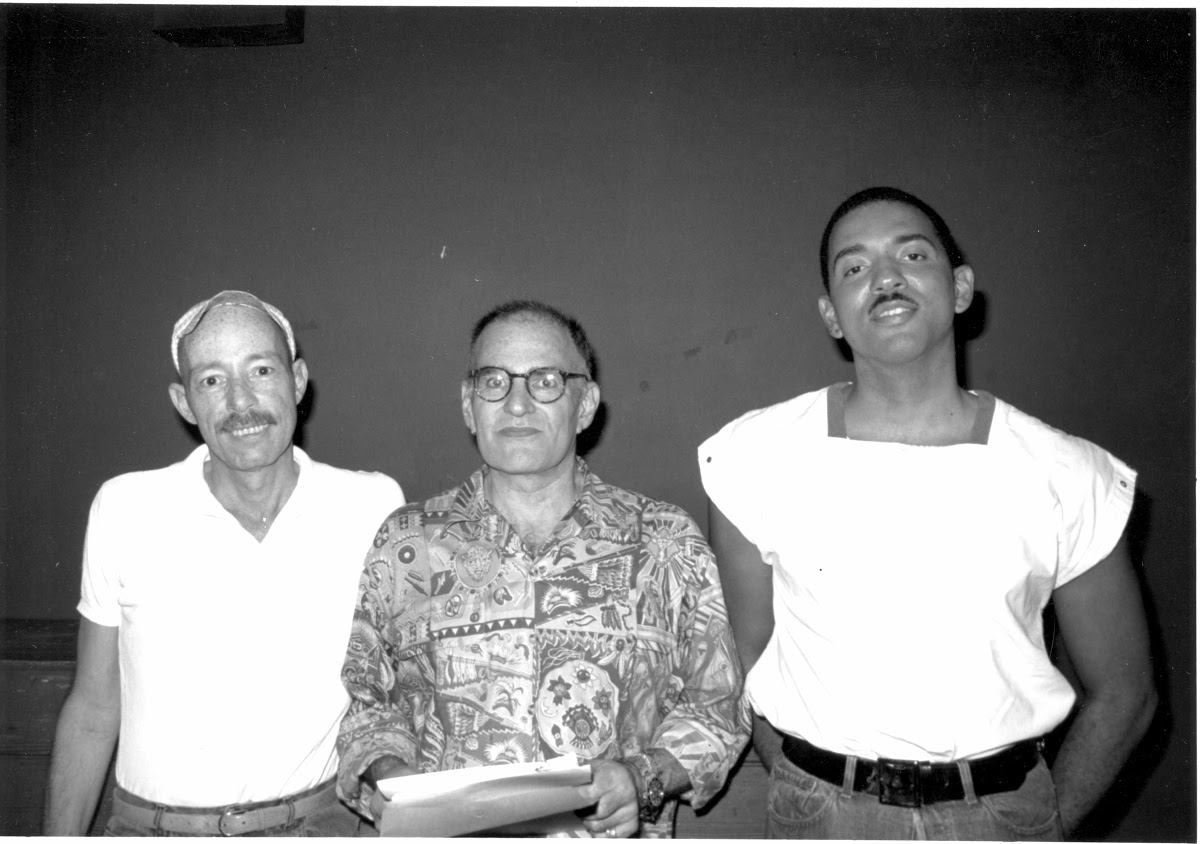

When Saint and Holmgren were diagnosed with HIV in 1987, Saint became increasingly involved in activism. Already active in Men of All Colors Together, he began serving on its HIV/AIDS Concerns Committee and participating in ACT UP demonstrations. He was among the earliest Black gay activists to publicly disclose his diagnosis, according to AIDS journalist Victoria A. Brownworth. He spoke unashamedly about his HIV status, including in Marlon Riggs’s documentary Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (No Regret) (1993), and urged other Black men to follow suit as a way toward destigmatization, visibility, and empowerment.

When we don’t show en masse the lives, the faces, and the hearts of AIDS—ours included—we are accepting all the connotations of shame, all the mystification of sin and repentance that those who are plainly simple-minded place on a virus.

In 1989, Saint established Galiens Press (a portmanteau of “gay” and “aliens”). Operating out of his apartment, Saint published two anthologies, including Lambda Award winner The Road Before Us, which showcased 100 Black gay poets. A “stepping-stone on the road to gay Black poetical empowerment,” Saint also recognized that these anthologies would serve as “testaments, testimonies, and legacies” of a generation of writers lost to AIDS, declaring that “Silence = Death. Writing = Life. Publishing = Survival.”

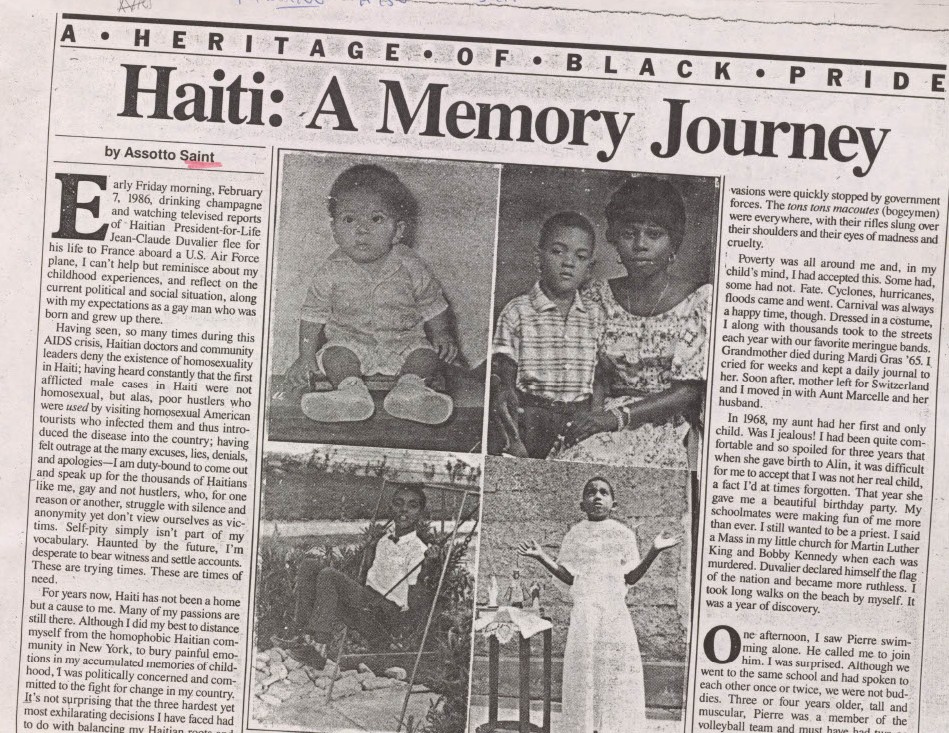

Saint also self-published two collections of poetry, chronicling trauma, anger, and resilience during the AIDS crisis while critiquing government inaction and racism against Haitians, whom many erroneously blamed for the epidemic. Through writing, Saint also grieved and memorialized those lost to AIDS, including friends, 21 neighbors, and, after his death in 1993, Holmgren.

In 1994, at age 37, Saint died of AIDS-related complications in his apartment. As he planned, friends carried his coffin through the streets from Redden’s Funeral Home at 325 West 14th Street to Metropolitan-Duane United Methodist Church. Saint and Holmgren are buried alongside each other at The Evergreens Cemetery in Queens, and a collection of his papers are held at the Schomburg Center.

Entry by Ethan Brown, project consultant (July 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Philip Birnbaum

- Year Built: 1963-65

Sources

Assotto Saint, “Haiti: A Memory Journal,” New York Native, March 3, 1986, bit.ly/46IgQKm.

Assotto Saint, The Road Before Us: 100 Gay Black Poets, 1957-1994 (New York: Galiens Press, 1991), bit.ly/3pxQGt9. [source of second pull quote]

Assotto Saint, “Why I Write,” Sacred Spells: Collected Works (Brooklyn: Nightboat Books, 2023), bit.ly/3JGcSb8. [source of first pull quote]

Assotto Saint, Wishing for Wings (New York: Galiens Press, 1994), bit.ly/3poNa4l.

Darius Bost, “‘A Voice Demonic and Proud’: Shifting the Geographies of Blame in Assotto Saint’s ‘Sacred Life: Art and Aids,’” AIDS and the Distribution of Crises, ed. Jih-Fei Cheng, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 148-161.

Emmanuel S. Nelson, Contemporary Gay American Poets and Playwrights: An A-to-Z Guide (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2003).

Erin Durban-Albrecht, “The Legacy of Assotto Saint: Tracing Transnational History from the Gay Haitian Diaspora,” Journal of Haitian Studies 19, no. 1 (Spring 2013), 235-256.

Jaime Shearn Coan, “Corporeal Archives of HIV/AIDS: The Performance of Relation” (Ph.D. diss., The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2020), bit.ly/46cXvAW.

Michele Karlsberg (literary executor of Assotto Saint), email with Ethan Brown, July 2023.

Victoria Brownworth, “Remembering Assotto Saint: A Fierce and Fatal Vision,” Lambda Literary, June 19, 2014, bit.ly/3r93EOi.

Walter Holland, email with Ethan Brown, June 2023.

Walter Holland, “The Calamus Root: American Gay Poetry Since World War II” (Ph.D. diss., The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 1998), bit.ly/3NXdOKQ.

Read More

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?