Pauli Murray Residence

overview

From 1947 to 1960, the prominent Black civil rights attorney and author Pauli Murray lived in an apartment on the top floor of this building.

During those years she compiled her encyclopedic States’ Laws on Race and Color, wrote a critically-acclaimed family history, Proud Shoes, and formed a long-term relationship with Irene (Renee) Barlow, which endured until Barlow’s death in 1973.

History

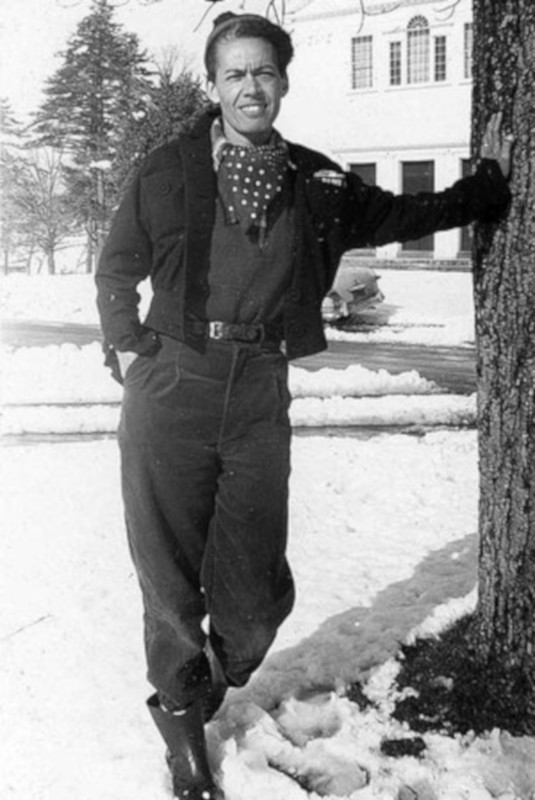

A major strategist in the struggle for Black and women’s rights, Pauli Murray (1910-1985) grew up in Durham, North Carolina. She graduated from New York City’s Hunter College in 1933. In her twenties, Murray became aware of her attraction to women. Based on her reading of the sex theorists of the day, principally Havelock Ellis, she thought of herself as a more male than female “invert” or “pseudo-hermaphrodite.” She began experimenting with names, including “Pete,” “Dude,” and “Paul,” before settling on “Pauli” and dressed as a Boy Scout or young sailor on hitchhiking trips with girlfriends.

In the 1940s, Murray earned a JD from Howard University and an LLM degree from the University of California’s Boalt Hall Law School. Returning to New York City in 1946, she worked with Bayard Rustin and George Houser in planning the Congress of Racial Equality’s (CORE) 1947 “Journey of Reconciliation,” which challenged racial segregation on interstate buses. A job with Charles L. Kellar, the Brooklyn attorney, who owned the building at 388 Chauncey Street, prompted her to move there in 1947. Until the mid-1950s, she shared her apartment with her two elderly aunts, Pauline Dame and Sallie F. Small.

After she was admitted to the New York State bar in 1947, Murray began practicing in Manhattan, eventually opening her own office at 6 Maiden Lane. In 1949, the Women’s Division of the Methodist Church, which wanted to open church-related services to all races, hired Murray to prepare an analysis of the various state laws on race. Published in 1951, the study was so comprehensive and thorough that the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) made copies “available to law libraries, black colleges, and progressive organizations across the nation.” Thurgood Marshall called it “the Bible” for civil rights litigators and distributed the study to all the lawyers on his staff at the NAACP. Two years later, Murray again had a major impact on the NAACP team, when, at the suggestion of one of her Howard classmates, her final law school paper, laying out a strategy to overthrow segregation as a violation of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, was used to prepare the Supreme Court case for Brown v the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

In 1953, Murray, who had been publishing articles and poetry in African-American journals since her college years, began working full time on Proud Shoes, a family history from her viewpoint as a young mixed-race girl growing up in the Jim Crow South. Published in 1956, the book received excellent reviews, and, according to Murray’s biographer Rosalind Rosenberg, eventually “became a staple of American Studies courses.”

From 1956 to 1960, Murray worked as an attorney at the prestigious law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, & Garrison, where she met and became involved with Renee Barlow, the firm’s office manager. Although Murray and Barlow never lived together, they enjoyed a loving and rewarding partnership.

In 1962, during the administration of President John F. Kennedy, Murray was asked by Eleanor Roosevelt, a long-time mentor and friend, to join the President’s Commission on the Status of Women Committee (PCSW) on Civil and Political Rights. She became one of the founders of NOW, worked for the ACLU on a landmark case in Alabama overturning a ban on women serving on juries, and authored a number of important articles. Her work was so influential for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, that Ginsburg listed Murray as a co-author in Reed v Reed, her first Supreme Court brief in her long fight to end gender discrimination. Seeking renewal following Barlow’s death in 1973, Murray gave up the law and a tenured professorship at Brandeis to study theology. In 1977, she was the first African-American woman ordained a priest by the Episcopal Church. She died in Pittsburgh in 1985 and was interred in Brooklyn, at Cypress Hills Cemetery, in a family plot she shared with her aunts, Renee Barlow, and Barlow’s mother, Mary Jane.

Murray’s childhood home in Durham, North Carolina, has been preserved as the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice and, in 2016, was designated a National Historic Landmark.

Entry by Gale Harris, project consultant (August 2019), and made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown

- Year Built: c. 1893-95

Sources

Duke Human Rights Center, Pauli Murray Project, www.paulimurraycenter.com.

Kathryn Schulz, “The Many Lives of Pauli Murray,” New Yorker, April 17, 2017.

Patricia Bell-Scott, The Firebrand and the First Lady (New York: Borzoi Books: Knopf, 2016).

Pauli Murray, Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family (1956, 2nd ed. New York: Harper Row, 1978).

Pauli Murray, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, 1987; reprinted as Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest, and Poet (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989).

Rosalind Rosenberg, Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?