Month: September 2022

City takes first step toward landmarking Julius’ Bar

September 13, 2022

By: Maya Rajamani

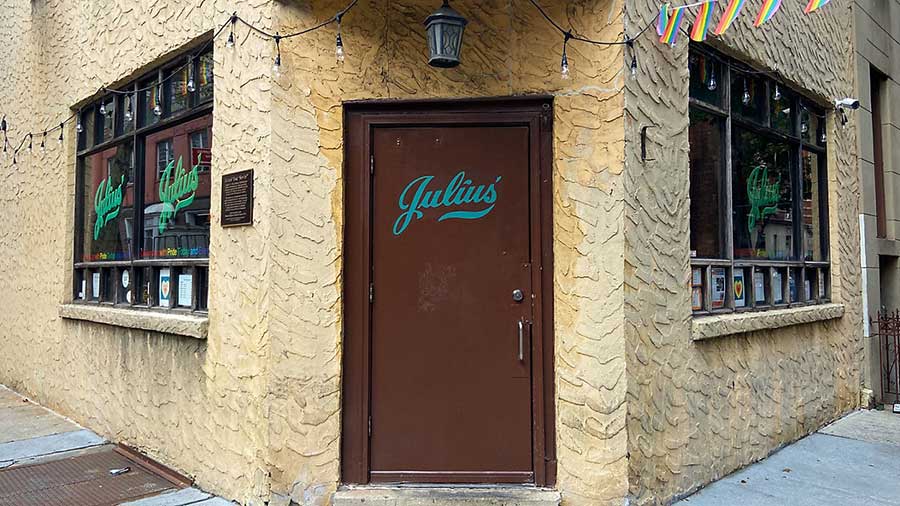

The oldest gay bar in the five boroughs, Greenwich Village stalwart Julius’ Bar, is on track to become a New York City landmark.

Members of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission unanimously voted during a public hearing Tuesday morning to “calendar” the West 10th Street building that houses the bar.

In 1966, the bar was the site of what was called a “Sip-In,” a protest against regulations that made it illegal to serve people suspected of being gay or lesbian.

“Calendaring” a site, or scheduling a public hearing to discuss its significance, is the first official step in the process of designating a landmark, according to the LPC.

“We have staff working specifically on identifying sites that are significant to the LGBTQ community and heritage in the city,” LPC Chair Sarah Carroll said at the hearing. “And this has always been one that we have been thinking about.”

The commission will hold the public hearing “in the near future this fall,” Carroll added, without providing an exact date.

Built in the early 1800s as a trio of standalone buildings that were later combined, the Arts and Crafts style building “has housed a bar since the 1860s,” LPC Director of Research Kate Lemos McHale said at the hearing.

The present-day Julius’ Bar at 159 West 10th St., at the corner of Waverly Place, opened its doors in 1930, she said.

In the 1950s, the watering hole became a popular gathering place for gay men, “despite its management’s unwelcoming attitude toward them, mixing in among the bar’s mostly straight clientele,” she added.

By the early 1960s, the city had begun taking steps to crack down on bars and restaurants that served gay people, as the State Liquor Authority had deemed serving them illegal. A police raid stemming from that crackdown sparked the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, which served as a turning point for the city’s LGBTQ rights movement.

Three years before Stonewall, however, three members of the Mattachine Society — a gay rights organization — made history by holding a “Sip-In” at Julius’ Bar.

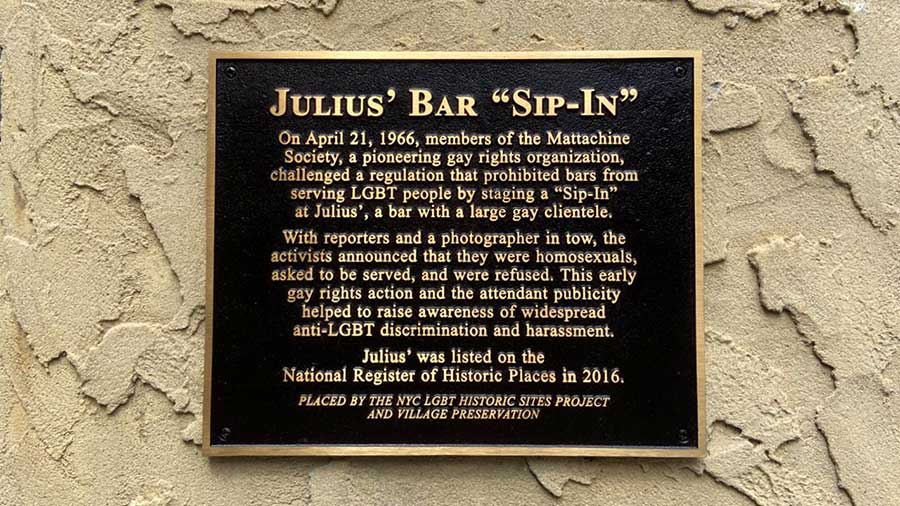

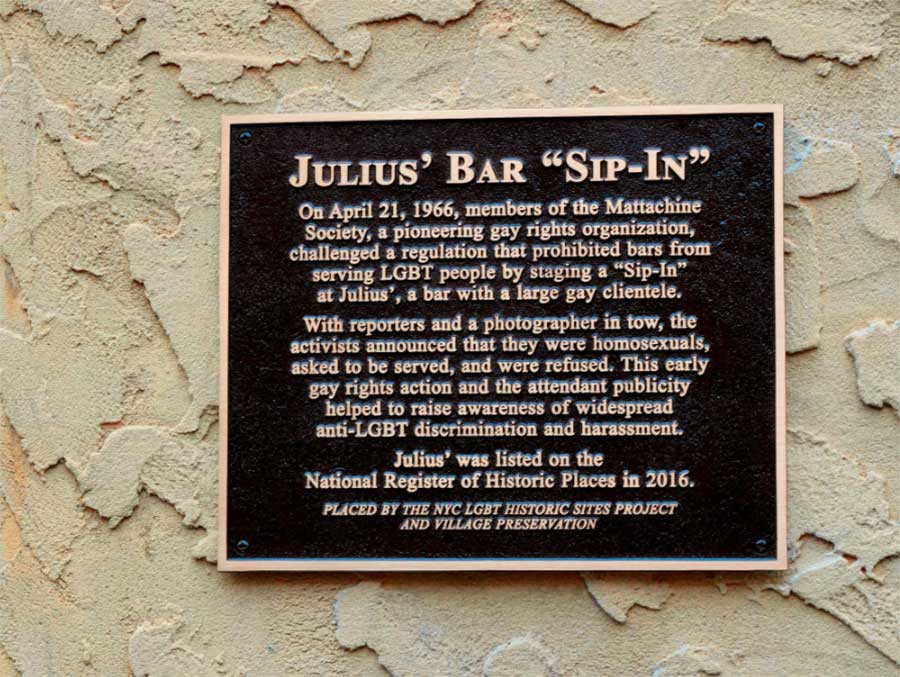

“With reporters and a photographer in tow, the activists announced that they were homosexuals, asked to be served, and were refused,” a plaque Village Preservation and the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project fastened to the bar’s facade earlier this year reads.

“This early gay rights action and the attendant publicity helped to raise awareness of widespread anti-LGBT discrimination and harassment,” it adds.

While the National Register of Historic Places listed Julius’ Bar in April 2016, Tuesday’s hearing marked the first time the city has formally considered landmarking it.

In a press release Tuesday morning, Village Preservation said the LPC’s vote followed a “nine-year campaign” to see the bar become a city landmark.

The LPC designated the Stonewall Inn a landmark in June 2015.

“This is a tremendously important step toward conferring much-needed recognition and protection upon this site, which played such an enormously important role in the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement,” Village Preservation Executive Director Andrew Berman said in a statement.

“LGBTQ+ and civil rights history like that which is embodied in Julius’ Bar are essential elements of our collective story, and it’s critical that they not be forgotten or erased,” Berman added.

Julius’, New York City’s oldest gay bar, is one step closer to becoming a city landmark

September 13, 2022

By: Devin Gannon

New York City’s oldest gay bar is on its way to becoming an individual landmark. The Landmarks Preservation Commission on Tuesday voted to calendar Julius’ Bar, a Greenwich Village establishment known for its historic 1966 “Sip-In” when members of the Mattachine Society protested the state law that prohibited bars from serving “suspected gay men or lesbians.” Considered one of the city’s most significant sites related to LGBTQ+ history, Julius’ Bar played an instrumental role in advancing the rights of gay New Yorkers.

Located on the corner of West 10th Street and Waverly Place, the building that is now home to Julius’ was constructed in the early 19th century as three separate structures that were later combined into one building. The property has held a bar since the 1860s; Julius’ Bar opened in the 1930s. By the 1960s, gay men started meeting at the bar, despite “unwelcome attitudes.”

On April 21, 1966, three years before the Stonewall Riots, members of the gay rights group the Mattachine Society organized a “Sip-In,” a non-violent protest inspired by the sit-ins of the Civil Rights Movement. The purpose of the sip-in was to challenge the New York State Liquor Authority rules put into effect so bars could not serve drinks to known or suspect gay men or lesbians.

According to the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell, and John Timmons visited several bars, announced that they were “homosexuals,” and ordered a drink. At Julius’, the group was refused. The demonstration led to a court ruling a year later that determined gay people had the right to assemble and be served alcohol, and over time, the growth of bars as social spaces for the LGBTQ+ community.

While the building that houses Julius’ Bar has seen changes over time, including its Arts and Crafts style stucco facade from the 1920s. After structural issues were discovered in the 1980s, the building was “essentially reconstructed with the same appearance,” according to the LPC, with a “restorative approach” approved by the commission. Small changes include the bar’s window openings, replacement of pattern brickwork, and the addition of a faux cornice, but it retains its integrity from the period of significance in the 1960s.

Advocates have pushed for Julius’ to be recognized for its significance. Thanks to an effort led by the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, the bar was listed on the New York State Register of Historic Places in 2015 and the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

Historic preservation group Village Preservation has pushed LPC to designate Julius’ as a city landmark for nearly a decade. In April, Village Preservation and the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project unveiled a plaque at Julius’ Bar to mark the significance of the Sip-In.

“It’s so important that we not only honor sites like these that tell the diverse stories of our city and country’s history and culture but that we take affirmative steps like landmarking to ensure they are forever preserved,” Andrew Berman, executive director of Village Preservation, said in a statement.

“LGBTQ+ and civil rights history like that which is embodied in Julius’ Bar are essential elements of our collective story, and it’s critical that they not be forgotten or erased. We’re very fortunate that Greenwich Village is so rich in these threads of our history, and we’re committed to ensuring they are recognized and preserved, for everyone’s benefit.”

Calendaring a property is the first step in the designation process, followed by a public hearing and a vote.

City to consider landmarking Julius’ Bar

September 13, 2022

By: Matt Tracy

The building housing Julius’ Bar, which is known as the oldest gay bar in New York City and the site of the 1966 “sip-in” event that helped catapult the right to drink for LGBTQ people, could soon be formally recognized as a city landmark.

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) voted on September 13 to “calendar” — or set up for formal consideration — the bar’s building at 159 West 10th Street in Greenwich Village. The law stipulates that the LPC must hold a hearing and vote on landmarking the building within a year, according to Village Preservation, which is a non-profit organization dedicated to saving the architectural and cultural history of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo.

Julius’ building holds particular significance in LGBTQ history thanks to the sip-in demonstration that took place on April 21, 1966 — three years before Stonewall — when Mattachine Society members Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell, John Timmons, and Randy Wicker challenged the State Liquor Authority’s policy barring bartenders from serving LGBTQ people.

The four individuals, accompanied by the press, entered multiple bars and said, “We are homosexuals. We are orderly, we intend to remain orderly, and we are asking for service.” The first bars they entered were willing to pour them drinks, so they continued on to Julius’ bar, where a bartender placed his hand over a glass to demonstrate his refusal to serve them.

Advocates have long pushed for Julius’ to get landmark designation, which prevents significant changes to the building in the future, but that campaign is largely symbolic because the building that houses Julius’ already sits within the landmarked Greenwich Village Historic District. That area encompasses a collection of more than 2,000 buildings over 100 blocks in Manhattan.

“[Landmarking] the bar is very important because it marked one of the few sites that really predate even Stonewall in the beginning of the movement,” Wicker, a longtime LGBTQ activist, told Gay City News on September 13 as he recalled his role in the sip-in protest.

Village Preservation’s executive director, Andrew Berman, said the organization has been a proponent of the push to landmark Julius’ building for nine years.

“This is a tremendously important step toward conferring much-needed recognition and protection upon this site, which played such an enormously important role in the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement,” Berman said in a written statement. “We’re optimistic that it will soon join the ranks of other officially designated LGBTQ+ landmarks in our neighborhood which we fought for…”

Berman, Wicker, and others joined together at Julius’ in April of this year to mark the 56th anniversary of the sip-in. To this day, Wicker remembers walking from bar to bar as he and others sought to bring attention to the state’s discriminatory policy.

“Julius’ didn’t want to be a gay bar,” Wicker said. “In the afternoon, people in the neighborhood would stop in and have a beer and socialize, but because there was a large population of gay people in neighborhood, they had a large clientele. On the weekends, they kept an eye on how many males and females were in the bar because they didn’t want it to tip over into being all male.”

While other bars were willing to look the other way and serve the men regardless of the liquor law, Julius’ was on edge after one man was recently entrapped and arrested prior to the sip-in.

“[Julius’] got notice that the liquor license could be revoked if you got another incident like this, so that was the reason they really refused us,” Wicker added. “Because the police department could do this so they could start getting payoffs from Julius’. The precinct was very corrupt in that way.”

The rise of public-facing gay bars, Wicker said, helped spark further advances for LGBTQ rights and even drew the attention of political figures who started to realize the voting power of queer people in the area.

“Politicians started going to those bars seeking votes,” Wicker said.

Berman welcomed the LPC’s vote to consider the building, but he also emphasized that such designations are also needed for other places that hold significance in LGBTQ history.

“We hope the LPC will also take some not just symbolic actions to landmark LGBTQ+ historic sites currently entirely lacking in protection, which could actually be lost or compromised in some way,” he said, pointing to a list of sites rich with LGBTQ history. Those locations include spots like 55 Fifth Avenue, which was home to Columbia Photograph Recording Studios and OKeh Phonograph Recording Studios and brought in notable LGBTQ performers such as Blues singer Bessie Smith; 86 University Place, which was the site of a popular lesbian bar called “The Bag” and attracted customers such as Audre Lorde; and St. Ann’s Church at 120 East 12th Street, which hosted a funeral mass for trans performer Jackie Curtis in 1985.

The LGBTQ spots already landmarked by the city include the Stonewall Inn, which was landmarked in 2015, as well as six more sites that were designated as landmarks in 2019 — the year New York City hosted WorldPride: Caffe Cino at 31 Cornelia Street, the LGBT Community Center at 208 West 13th Street, the Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse at 99 Wooster Street, James Baldwin’s residence at 137 West 71st Street, the Women’s Liberation Center at 243 West 20th Street, and Audre Lorde’s residence at 207 St. Paul’s Avenue on Staten Island.

“LGBTQ+ and civil rights history like that which is embodied in Julius’ Bar are essential elements of our collective story, and it’s critical that they not be forgotten or erased,” Berman added. “We’re very fortunate that Greenwich Village is so rich in these threads of our history, and we’re committed to ensuring they are recognized and preserved, for everyone’s benefit.”

One of New York City’s oldest gay bars could become city landmark

September 13, 2022

By: Eyewitness News

In April, Village Preservation and the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project unveiled a plaque at Julius’ Bar to mark the significance of the sip-in.

Calendaring a property is the first formal step in the designation process, followed by a public hearing and a vote.