Month: April 2018

Today in LGBT History: Bombing at Uncle Charlie’s

20180428

Uncle Charlie’s, which opened in 1980 at 56 Greenwich Avenue and closed in September 1997, was one of the city’s most popular gay video bars and one of the first to appeal to gay men of the MTV generation. The bar, with its large modern interior and television screens, was a stark contrast to the prior generation of gay bars that were perceived as outdated and dark. It attracted a “younger, suit-and-tie crowd” and, over time, gained a reputation as a so-called “S and M” (Stand and Model) bar, due to the fact that numerous patrons stared more at the TV screens than talk with each other. On April 28, 1990, at 12:10 a.m., a homemade pipe bomb exploded, injuring three men who were later treated for minor injuries at nearby St. Vincent’s Hospital. The bomb was made from several M-80 firecrackers that were stuffed into a six-inch length of pipe. It had no timing device and was lighted and placed in a garbage can inside the bar moments before the blast.

On April 28, 1990, at 12:10 a.m., a homemade pipe bomb exploded, injuring three men who were later treated for minor injuries at nearby St. Vincent’s Hospital. The bomb was made from several M-80 firecrackers that were stuffed into a six-inch length of pipe. It had no timing device and was lighted and placed in a garbage can inside the bar moments before the blast. Although the police said the blast did not appear bias-related, Mayor David Dinkins and several gay rights groups characterized it as an anti-gay attack since Uncle Charlie’s was a well-known gay bar. The recently formed Queer Nation and other groups organized a demonstration of almost 1,500 protesters from Uncle Charlie’s to the Sixth Precinct at 233 West 10th Street, carrying a banner that read “Dykes and Fags Bash Back.” The Mayor released a statement calling the bombing the 26th bias incident against the LGBT community that year.

Although the police said the blast did not appear bias-related, Mayor David Dinkins and several gay rights groups characterized it as an anti-gay attack since Uncle Charlie’s was a well-known gay bar. The recently formed Queer Nation and other groups organized a demonstration of almost 1,500 protesters from Uncle Charlie’s to the Sixth Precinct at 233 West 10th Street, carrying a banner that read “Dykes and Fags Bash Back.” The Mayor released a statement calling the bombing the 26th bias incident against the LGBT community that year.

Queer Nation was founded March 1990 at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center (now the LGBT Community Center) with the mission of eliminating homophobia and increasing LGBT visibility. Its four founders (Tom Blewitt, Alan Klein, Michelangelo Signorile, and Karl Soehnlein) were members of ACT UP New York. They were outraged by the escalation of violence against LGBT people in the streets of New York, and the continued existence of anti-gay discrimination. The group’s name was an early re-appropriation of the word “queer” as a political identity. Their rallying cry during demonstrations was: “We’re here! We’re Queer! Get used to it!” The group developed chapters in cities nationwide, including Atlanta, Denver, Houston, Portland, and San Francisco.

In 1995, the blast at Uncle Charlie’s was discovered to have been one of the first terrorist attacks on U.S. soil by a radical Muslim group. The New York Times reported that El Sayyid A. Nosair, one of the leaders on trial for the terrorist conspiracy to blow up New York City landmarks, allegedly planted the bomb at Uncle Charlie’s as a protest against homosexuality on religious grounds. The trial resulted in Nosair being sentenced to life in prison.

In 1995, the blast at Uncle Charlie’s was discovered to have been one of the first terrorist attacks on U.S. soil by a radical Muslim group. The New York Times reported that El Sayyid A. Nosair, one of the leaders on trial for the terrorist conspiracy to blow up New York City landmarks, allegedly planted the bomb at Uncle Charlie’s as a protest against homosexuality on religious grounds. The trial resulted in Nosair being sentenced to life in prison.

Photos, top to bottom:

Uncle Charlie’s bar on Greenwich Avenue, October 1992. Photo by Ken Lustbader.

Interior of Uncle Charlie’s, c. 1990s. Source: Then and Now: Uncle Charlie Remembers Queer Memories of New York Facebook Page.

May 16, 1990 Outweek article by Andrew Miller and Duncan Osborne about the bomb and protests. Photo by Tracy Litts. Sources:

Andrew Miller and Duncan Osborne, “Bombing at Gay Bar Raises Community Ire,” Outweek, May 16, 1990.

David Bahr, “Uncle Charlie’s Closes and With It, Perhaps, an Era,” The New York Times, September 21, 1997.

James C. McKinley Jr., “Bomb Explodes at a Gay Bar, Prompting a Protest,” The New York Times, April 29, 1990.

James C. McKinley Jr., “Many Accused in Terror Plot Bombed Gay Bar, U.S. Says,” The New York Times, January 15, 1995.

“Today In Gay – April 28, 1990: Bomb Explodes At Uncle Charlie’s Downtown NYC Later Found Out To Be Terrorist Attack,” Back2Stonewall, April 28, 2017, https://bit.ly/2Hwijvl.

“Uncle Charlie’s Downtown”, Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York, February 20, 2014, https://bit.ly/2HZqFLC.

PHOTOS: LGBT advocates honor 52nd Anniversary of historic “Sip-In” with trailblazer Dick Leitsch and advocate/influencer Adam Eli

April 26, 2018

PHOTO RELEASE

PRESS CONTACT

Ken Lustbader, NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

p: (917) 848-1776 / e: [email protected]

** PHOTOS **

Generations come together at LGBT anniversary event

LGBT civil rights trailblazers Randy Wicker, Dick Leitsch — mastermind

of 1966 Mattachine Society “Sip-In” — and new guard activist Adam Eli

share a toast a Julius’ Bar

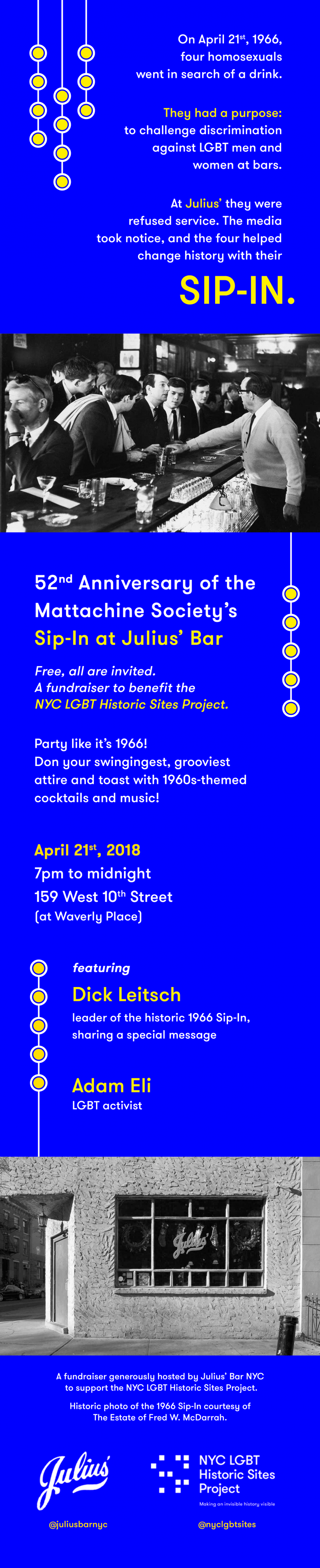

New York, NY–LGBT advocates and NYC preservationists celebrated history on Saturday, April 21st, at Julius’ Bar in Greenwich Village, the site of the historic 1966 “Sip-In” organized by the Mattachine Society, an early American homophile group.

Trailblazer and mastermind of the “Sip-In” — one of the earliest acts of public resistance, which challenged discrimination against LGBT people in New York City — Dick Leitsch, as well as fellow Mattachine member and protest participant Randy Wicker, were joined by Adam Eli, whose own non-violent activism builds on the legacy of actions like the groundbreaking “Sip-in.”

Speaking to the standing-room-only crowd at Julius’, Adam Eli referenced the historic pendulum of progress in the community: “when the pendulum moves forward, it’s because we pushed it,” resisting periods of oppression and using our might to swing the pendulum back towards a period of increased rights and equality. “Tonight, honor your ancestors, thrive with your contemporaries and fight like hell on Monday,” he declared, in a moment (full speech here) which captured the spirit of inter-generational appreciation between pioneers Leitsch and Wicker and the young Eli, a force behind the activist group Voices4.

State Senator Brad Hoylman presented event organizers NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project and Julius’ Bar with a proclamation declaring April 21, 2018 to be “Julius’ Bar Appreciation Day,” in honor of Julius’ status as the “oldest LGBTQ bar in New York City still in operation” and the Sip-In’s status as “one of the first acts of gay civil rights disobedience in the United States of America.”

NYC Councilmember Daniel Dromm, Chair of the Council’s LGBT Caucus and himself a former teacher, praised the leadership of Dick Leitsch for his 1966 “Sip-In” and also the work of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project to document and disseminate LGBT history via its website, www.nyclgbtsites.org. Councilmember Dromm reinforced his support of LGBT history inclusion in public school curriculum.

View more photos of the

“Sip-In” 52nd Anniversary celebration (here).

Photos:

(1) Left to right, Helen Buford, owner of Julius’ Bar; NYC Councilmember Daniel Dromm; Dick Leitsch; Adam Eli, activist and social influencer; Jay Shockley, Project co-director; Randy Wicker; Ken Lustbader (with sign), Project co-director.

(2) Randy Wicker, participant of the 1966 “Sip-In” signs copies of the famous photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, of the Mattachine Society group being denied a drink by the bartender at Julius’.

(3) Dick Leitsch, mastermind of the 1966 Mattachine Society’s “Sip-In” joins with NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project manager Amanda Davis, donning a “Go-Go Mattachine!” button, for a fun photo.

(4) State Senator Brad Hoylman (right, with bowtie) presents a proclamation declaring April 21, 2018, to be “Julius’ Bar Appreciation Day,” in honor of its place in LGBT and American history.

Historical Background

Fifty-two years ago — on April 21st, 1966 — four homosexuals went in search of a drink. They had a purpose: to challenge discrimination against LGBT men and women at bars. At the time, the New York State Liquor Authority (SLA) enforced regulations making it illegal for bars to serve drinks to known or suspected gay men or lesbians, since their presence was considered de facto disorderly. The SLA regulations were one of the primary governmental mechanisms of oppression against the gay community because they precluded the right to free assembly. This was particularly important because bars were one of the few places where gay people could meet each other. Learn more about Julius’ as a site of LGBT history on our website (more).

At Julius’ Bar, they were refused service, the exchange with the bartender captured in a now-famous image by legendary photographer Fred W. McDarrah. Mainstream media took notice and what was called a “Sip-In” helped to change history.

As sites connected to LGBT history in NYC are threatened — the former site of the Paradise Garage has been demolished; 69 West 14th Street, site of the founding of the Gay Liberation Front, is actively threatened by the wrecking ball — it is more important than ever to remember the determination of LGBT equal rights pioneers and the physical sites which place key people and events in history.

About the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project is a cultural initiative and educational resource that is documenting historic sites connected to the LGBT community throughout New York City. Its interactive map features diverse places from the 17th century to the year 2000 that are important to LGBT history and illustrate the community’s influence on American culture. The Project is nominating sites to the National Register of Historic Places and developing educational tours and programs. For more, visit www.nyclgbtsites.org, or follow on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

###

DEMOLISHED: Paradise Lost

20180413

Demolition was completed on the former Paradise Garage site this month — the first LGBT historic site loss since the launch of the Project in 2015. At least one other site of LGBT significance is actively threatened by the wrecking ball: 69 West 14th Street, where the Gay Liberation Front held important community activities and political organizing in the immediate aftermath of the 1969 Stonewall uprising.

The demolition of the Paradise Garage underscores the urgency of our work: to document sites that shaped LGBT and American culture before they are lost.

Between 1977 and 1987, the Paradise Garage, at 84 King Street, was one of the most important and influential clubs in New York City with a devoted patronage comprised of sexual and ethnic minorities (primarily African-American gay men).

With resident DJ Larry Levan and other DJs as the center of attention, it influenced dance, music, and culture both nationally and internationally as the birthplace of the modern nightclub.

An Urgent Effort to Document New York’s LGBTQ History Before It Disappears

20180405

By: Muri Assunção

The former meeting place of the Gay Liberation Front is slated for demolition — but a group of historian-activists is racing to document sites like it, before they disappear.

A historic New York building that was the meeting place of the Gay Liberation Front — once a leading gay rights organization, and the first in the nation formed after the Stonewall Riots — has been marked for destruction. As the planned demolition approaches, a group devoted to LGBTQ history is racing to document sites like it, before they disappear.

A historic New York building that was the meeting place of the Gay Liberation Front — once a leading gay rights organization, and the first in the nation formed after the Stonewall Riots — has been marked for destruction. As the planned demolition approaches, a group devoted to LGBTQ history is racing to document sites like it, before they disappear.

The saga began two years ago, when the luxury real estate giant Extell Developments purchased four adjacent buildings in Greenwich Village, with plans of demolition reportedly set for next year. The $50 million deal was one of many Extell purchases from the family-run Duell Management, and it could’ve been seen as just another example of high-rise developments erasing old Manhattan’s charm. But the building at 69 West 14th Street, on the corner of 6th Avenue, has special significance for those who remember New York’s LGBTQ history.

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) mobilized in 1969, after a police raid and subsequent riot at the Stonewall Inn. The structure, built in 1909, not only housed the group’s social and political gatherings, but was also the site of major cultural contributions to New York City and beyond, such as housing both the first Merce Cunningham studio and The Living Theatre, a venue that once hosted a reading by Frank O’Hara and Gregory Corso. (They were famously heckled by a drunk Jack Kerouac.)

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) mobilized in 1969, after a police raid and subsequent riot at the Stonewall Inn. The structure, built in 1909, not only housed the group’s social and political gatherings, but was also the site of major cultural contributions to New York City and beyond, such as housing both the first Merce Cunningham studio and The Living Theatre, a venue that once hosted a reading by Frank O’Hara and Gregory Corso. (They were famously heckled by a drunk Jack Kerouac.)

Last month, as the last storefront tenants of the building — PMT Dance Studio and Moscot Eyewear, one of New York City’s oldest businesses — closed their doors, the inevitable wrecking ball felt as close as ever. And with it, an important cultural heritage site with ties to the very early days of the queer liberation movement seemed closer to extinction.

The planned demolition “is a real loss that shows the significance of LGBT spaces and cultural sites in the city should be recognized,” Ken Lustbader, a co-founder of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project told Hyperallergic. “We’re trying to get ahead of the curve proactively to identify these sites that show and convey LGBT history.”

The planned demolition “is a real loss that shows the significance of LGBT spaces and cultural sites in the city should be recognized,” Ken Lustbader, a co-founder of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project told Hyperallergic. “We’re trying to get ahead of the curve proactively to identify these sites that show and convey LGBT history.”

Lustbader, Jay Shockley, and Andrew Dolkart founded the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project as a nonprofit in 2014, after receiving a grant from the National Park Service —“the first ever LGBT-related grant given” by the agency, Shockley said. Their mandate was to identify and research sites that have been important historically and culturally to the LGBTQ community.

The project also nominates sites to the National Register of Historic Places, an honorary federal list that includes over 93,500 sites across the country. LGBTQ history remains seriously underrepresented, with less than 20 sites in the Register.

Since its inception, the Project has added five New York City sites. Earlier this year, Earl Hall at Columbia University was listed for its affiliation with the Student Homophile League, the first gay student organization in the country, founded in 1966 at Columbia University. Last year, it listed Greenwich Village’s Caffe Cino, and it amended the nomination to the Alice Austen House on Staten Island, which had been “written in the 1970s but needed to be amended to update her same-sex relationship and add more information about her pioneering transgressive photography.” Julius Bar and the Bayard Rustin Residence were added in 2016. (Stonewall was added to the registry in 1999, with help from Shockley and Dolkart.) This is first time in the four-year history of the organization that a site is actively being threatened with demolition. The threat of losing such an important piece of queer history underscores the urgency of the organization’s work: to document neglected, forgotten, and vanishing sites that shaped LGBTQ communities and American culture.

This is first time in the four-year history of the organization that a site is actively being threatened with demolition. The threat of losing such an important piece of queer history underscores the urgency of the organization’s work: to document neglected, forgotten, and vanishing sites that shaped LGBTQ communities and American culture.

This year, the Project partnered with New York City’s Historic District Council (HDC) in Six to Celebrate, an effort to “identify sites in the city that are significant related to cultural heritage.” The importance of this site, where GLF organized resistance to the persecution of LGBTQ communities, “cannot be overstated,” Shockley said.

For the organization’s founders, the importance of national history is matched by an awareness of local transformation. Lustbader and Shockley live blocks away from the GLF’s former meeting site. “There’s been increasing discussion over the last year about all new developments on 14th Street,” Shockley said, describing another planned demolition at an adjacent site. The 1952 building where Banksy recently drew his now-famous rat sold last year, for $42.4 million, is set to be torn down to make room for a condominium and retail space. That building also had a 110-foot-long mural in its lobby: Julien Binford’s “A Memory of 14th Street and 6th Avenue.” If it weren’t for the joint efforts of New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and the community-based preservation group Save Chelsea, that too, would’ve been destroyed forever. “14th Street, like every place else in Manhattan, is getting attacked by high rise development,” Shockley said.

For the organization’s founders, the importance of national history is matched by an awareness of local transformation. Lustbader and Shockley live blocks away from the GLF’s former meeting site. “There’s been increasing discussion over the last year about all new developments on 14th Street,” Shockley said, describing another planned demolition at an adjacent site. The 1952 building where Banksy recently drew his now-famous rat sold last year, for $42.4 million, is set to be torn down to make room for a condominium and retail space. That building also had a 110-foot-long mural in its lobby: Julien Binford’s “A Memory of 14th Street and 6th Avenue.” If it weren’t for the joint efforts of New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and the community-based preservation group Save Chelsea, that too, would’ve been destroyed forever. “14th Street, like every place else in Manhattan, is getting attacked by high rise development,” Shockley said.

There are currently 118 sites on the NYC LGBT Sites website. 400 have been nominated by the public and are currently in the project’s database. The process of researching and factually checking data is lengthy: “photographic documentation, multi-media, interviews,” said Lustbader. “We don’t want information that isn’t fully vetted.” Once they are satisfied with the factual accuracy, they make specific sites public “based on some priorities that include rarity, timing with anniversaries, and significance.”

As the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots approaches, the Project’s goal is to expand the research to past Manhattan, and to adapt their research for use in classrooms. Two more nominations to the National Register of Historic Places are also in the works, but their names can’t be announced yet, since consent from the property owners is needed. The organization is also working to secure “individual landmark” status for the Walt Whitman Residence in Brooklyn.

Photos, top to bottom: (1) 69 West 14th Street, as it appeared before the departure of its longtime tenant Moscot Eyewear (2016, courtesy Christopher D. Brazee and NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project); (2) The Stonewall Inn in 1969 (via Wikimedia); (3) Peter Hujar, “Gay Liberation Front Poster Image” (1969), gelatin silver print, 18 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches (courtesy The Morgan Library & Museum, © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC); (4) The Stonewall Inn as it appeared during Pride Week 2016 (via Wikimedia); (5) The cover of Ink, an alternative newspaper that covered the GLF in 1971 (via Wikimedia).

52nd Anniversary of the Sip-In at Julius’ Bar

April 21, 2018 | 7pm

Julius' Bar

159 West 10th Street, New York, New York

View on Google Maps