Documenting and celebrating lesbian nightlife in NYC

20171011

By: Karen Loew

In all of New York City, four lesbian bars: Henrietta Hudson’s and the Cubby Hole, both in the West Village; Ginger’s in Park Slope, Brooklyn; and the Bum Bum Bar (pronounced boom-boom), in Woodside, Queens.

Artist Gwen Shockey is documenting the dwindling number of spaces in New York City dedicated to lesbian nightlife. CityLab spoke with Shockey, on the occasion of her recent exhibition “No Man’s Land” at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, and with our own Ken Lustbader about the “grassroots” research Shockey employs, through archival research, oral histories and photography.

Preserving the Meaning of Lesbian Bars

As gay people and places are more accepted than ever, their bars are dwindling in number—especially for women. Now artists are documenting what these spaces mean to the community.

Photo: The bar at Henrietta Hudson’s in New York, photo by Karen Loew.

We rolled through the doors of Henrietta Hudson’s early on a weekend night. It was well before the club became electric, but my new pal Angola was already excited. “I gotta look around,” she said as we entered the first of three rooms, complete with dance floor, pool table, two bars, and seating nooks. “This is like the Vatican.”

Somehow, neither Angola nor I had visited Henrietta’s before. This venerable “bar and girl” in Manhattan’s West Village is one of only four lesbian bars still open for business in all of New York City. That sounds shocking until you learn that San Francisco has none at all. This fact is part of the reason we finally stopped by: It was a celebration following the opening of “No Man’s Land,” an artwork exhibition by Gwen Shockey on display at New York’s Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art. Her multimedia piece, installed for just one weekend in late September, responds to the reality of the dwindling number of spaces dedicated to lesbian nightlife.

At a time when gay people and places are more accepted than ever, the number of gay bars is declining. The decrease is far starker for women’s bars, because there were never as many of those in the first place. The causes include the “mainstreaming” that allows LGBTQ people to mingle elsewhere, the prevalence of hook-up apps, and the high cost of urban real estate. The circumstances vary in each place; some surmise, for example, that San Diego still sustains two lesbian bars because it’s a military town and a port town.

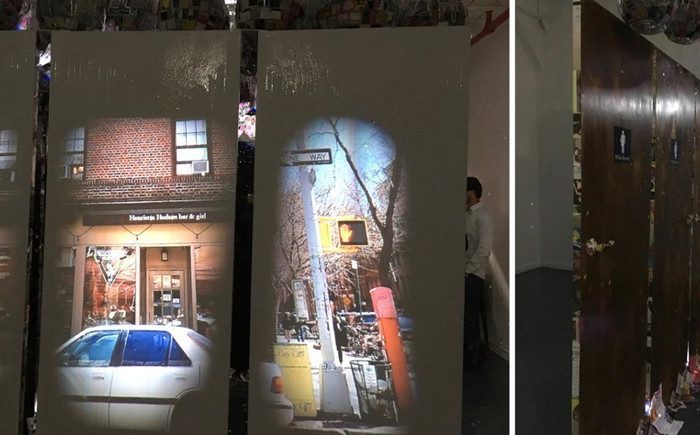

Scenes from the ‘No Man’s Land’ installation. Left: A video of Henrietta Hudson’s exterior. Right: A recreation of Henrietta Hudson’s restroom doors, with signs labeled “Whichever.” (Karen Loew)

Shockey’s exhibit echoes the scenes of New York’s four remaining lesbian bars. It feels like a bar in its own right: Lights are low, disco balls glint, drinks are poured, music plays, and visitors mingle. In the room with them are four unattached walls that represent the bars. On one side of each wall, a video shows a bar’s exterior; on the other side is a recreation of that bar’s bathroom doors. These four bars are Henrietta’s; the Cubby Hole, also in the West Village; Ginger’s in Park Slope, Brooklyn; and the Bum Bum Bar (pronounced boom-boom), in Woodside, Queens.

Shockey’s work laps into the realms of history, sociology, and preservation. Through recorded interviews with lesbians of every age and station, she’s learned about some 90 past bars and parties in New York, and photographed many of the addresses. Some of these interviews and prints will be included in her upcoming show in Brooklyn. Next, she’d like to make a book out of her photos and interviews, along with the histories she’s uncovered.

With this project, Shockey joins other gay artists whose work includes documenting the gay physical world, past and present—artists as concerned with spaces as with the body. Edie Fake makes intricate architectural drawings of real and imagined queer spaces from his native Chicago. Kaucyila Brooke has recorded and mapped past and present lesbian bars in three California cities, as well as Cologne, Germany. A faculty member at the California Institute of the Arts, Brooke says she began her ongoing project, “The Boy Mechanic,” in 1996 because, “It just felt pressing.” She wanted to capture the memories of places before they were lost—even though many of the places themselves weren’t much to look at.

Still, they must be seen, so Brooke took up documenting vernacular architecture: the everyday, often undistinguished structures that fill so much of the built environment.

“You have buildings that are designed to be something, by an architect,” she says. “But lesbian bars were usually something else before. And the bar owner tries to change the interior. This architecture that gets adapted and turned into something… is just interesting to me in terms of reusing things.”

It’s part of the “thrift economy” that expresses the “fugitive” nature of space for women and lesbians. Lesbian bars generally have understated facades, for example, in order to draw less attention from hostile men or police authorities.

Her photographs, videos, and other media have “to do with space, instead of looking at the body. Can you recognize anything by looking at a space? [Like] the difference between the surface and what’s underneath it, or inside of it?”

People who are trained in just that kind of detective work launched another effort—with more history, less art—two years ago. A team of historic preservation professionals is behind the NYC LGBT Sites Project, which aims to become an all-encompassing documentation of places where LGBT people have gathered—particularly when they illuminate the community’s impact on American culture. The project’s goal of “making an invisible history visible” is enriched by all kinds of participation, says Co-Director Ken Lustbader.

“We are really interested in having people understand the visceral connection to a location,” Lustbader said. “One of the most interesting ways that this [documentation] is being done is by the enthusiasts, and the more grassroots historians.”

That includes Shockey’s trove of interviews, Hugh Ryan’s research on the queer Brooklyn waterfront, or any number of entertaining Instagram accounts. In fact, it seems possible that whether rooted in New Orleans or floating on the internet, the diverse collectors of this invisible history are just getting started.

Because one thing’s for sure, lesbian bars are still essential. The heartbreaking words of interviewees in Brooke’s San Diego video still ring true. “Everybody out there was against us. And we would go into this little dark place, it was a bar, and find each other. And become friends. And care about each other,” one woman says.

“It was just nice to be in an environment where you could just be free. And just relax,” says another.

Ask the tall, skinny dyke from New Zealand who was having a high time at Henrietta Hudson’s on her very first night in New York City, already kissing a pretty girl and taking recommendations on where to find the best fried chicken. Or the handsome trans woman, recently moved to NYC from North Carolina, who happily accepted Angola’s offer to “be her gay mom” (and, impressively, set off to visit the three other lesbian bars in a single night). Or the bar patron who received advice from E., the mellow-fabulous bartender, on how to get a traditional male barber to cut a woman’s hair. Or anyone on the soon-crowded dance floor, if you could peel them away.

Lesbian and bisexual women of every description were free, and relaxed, and finding each other. It’s a thing of the present, not just the past.

Click to read the article on CityLab.