overview

On April 21, 1966, a “Sip-In” was organized by members of the Mattachine Society, one of the country’s earliest gay rights organizations, to challenge the State Liquor Authority’s discriminatory policy of revoking the licenses of bars that served known or suspected gay men and lesbians.

The publicized event – at which they were refused service after intentionally revealing they were “homosexuals” – was one of the earliest pre-Stonewall public actions for LGBT rights as well as a big step forward in the eventual development of legitimate LGBT bars in New York City.

Through the efforts of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, this site was listed on the New York State Register of Historic Places in 2015 and the National Register of Historic Places in 2016. The Project’s advocacy also led to the site’s designation as a New York City Landmark by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2022.

History

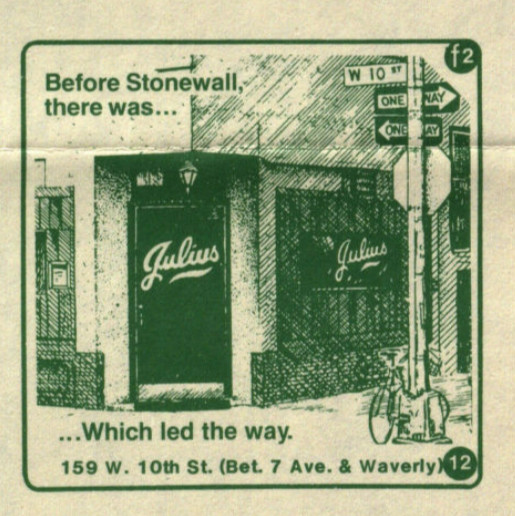

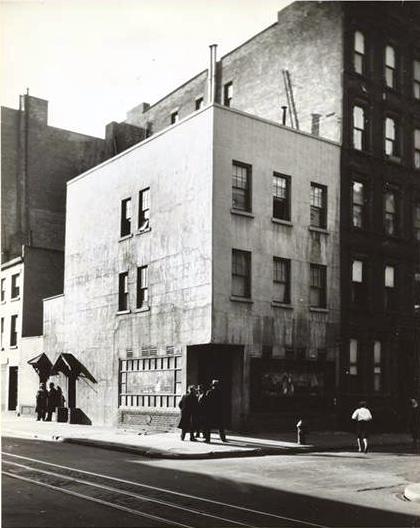

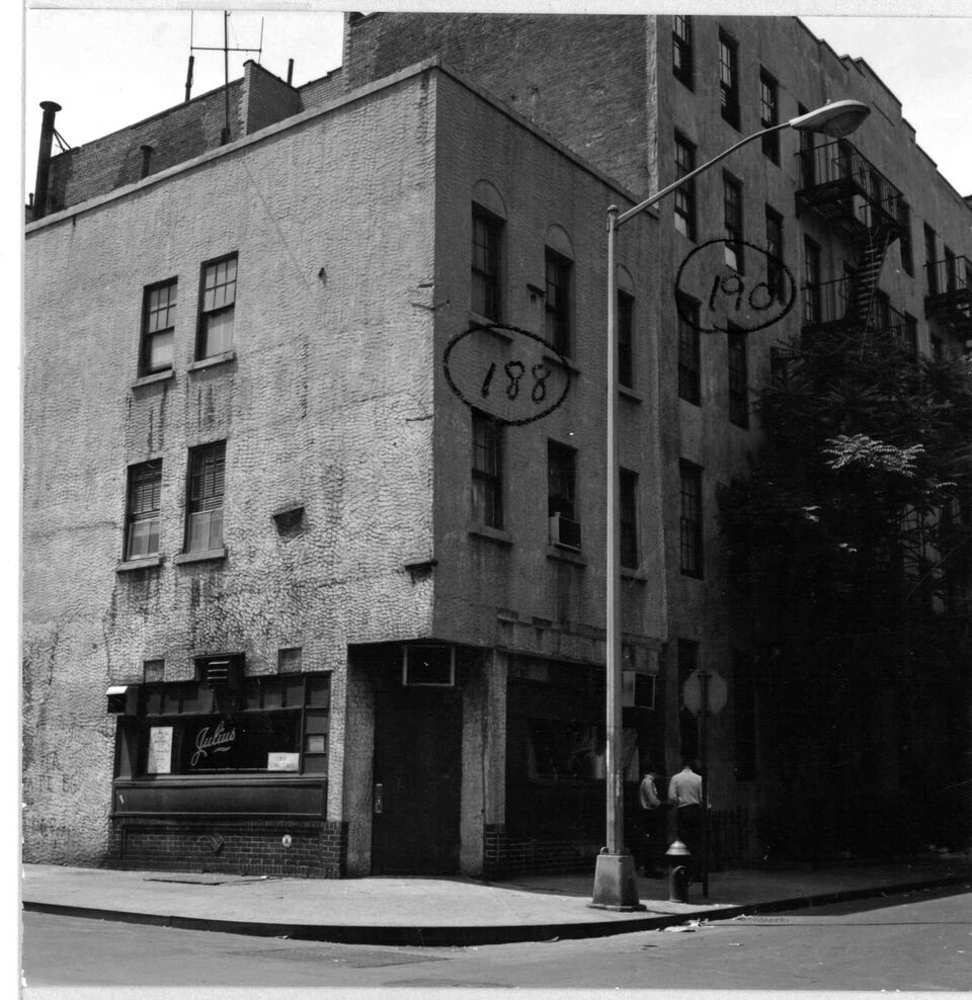

There has been a bar on the corner of Waverly Place and West 10th Street since the mid-19th century. The name Julius’ dates from c. 1930 when the bar began to become popular with sports figures and other celebrities. By the 1960s, Julius’ began attracting gay men, although it was not exclusively a gay bar.

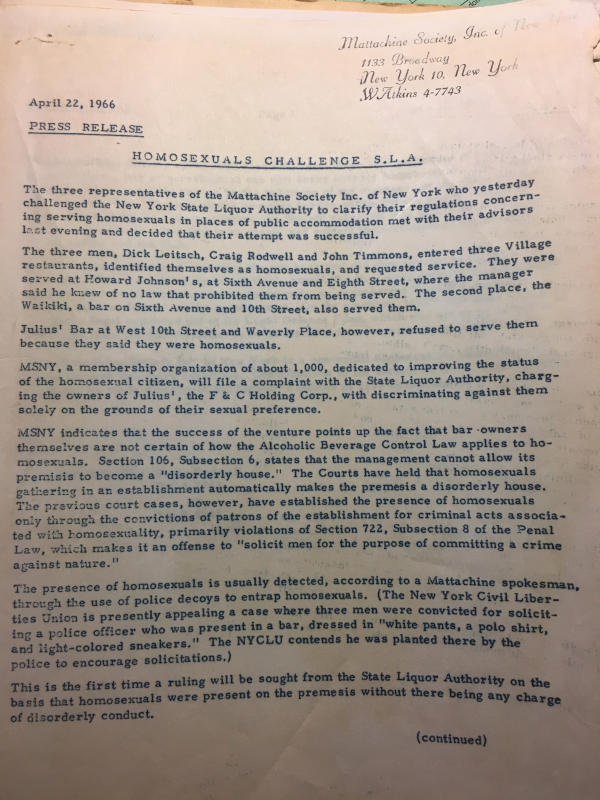

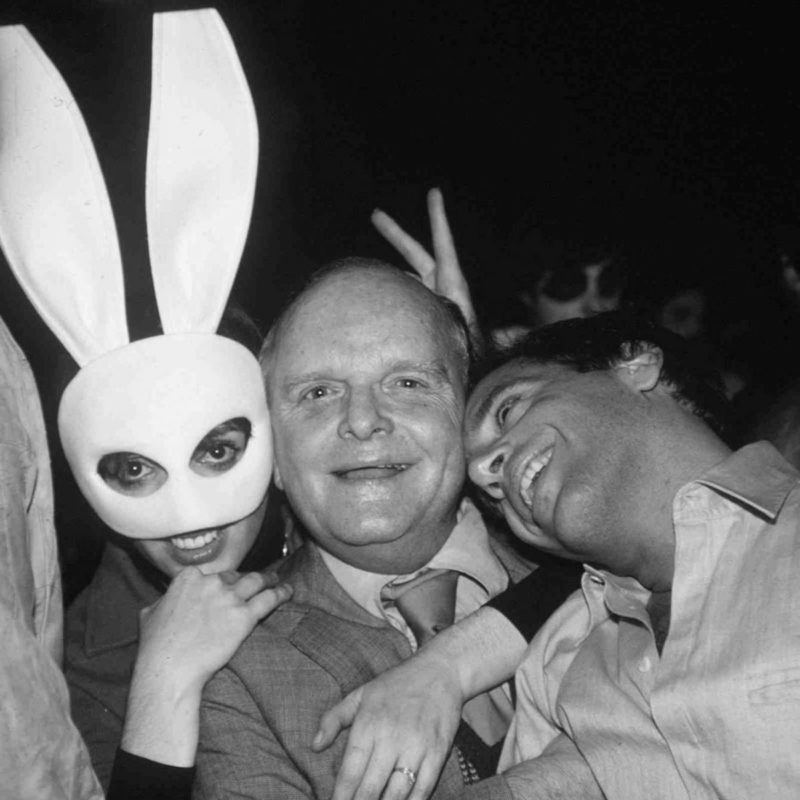

On April 21, 1966, members of the Mattachine Society, an early gay rights group, organized what became known as the “Sip-In.” Their intent was to challenge New York State Liquor Authority (SLA) regulations that were promulgated so that bars could not serve drinks to known or suspected gay men or lesbians, since their presence was considered de facto disorderly. The SLA regulations were one of the primary governmental mechanisms of oppression against the gay community because they precluded the right to free assembly. This was particularly important because bars were one of the few places where gay people could meet each other. The Sip-In was part of a larger campaign by more radical members of the Mattachine Society to clarify laws and rules that inhibited the running of gay bars as legitimate, non-mob establishments and to stop the harassment of gay bar patrons.

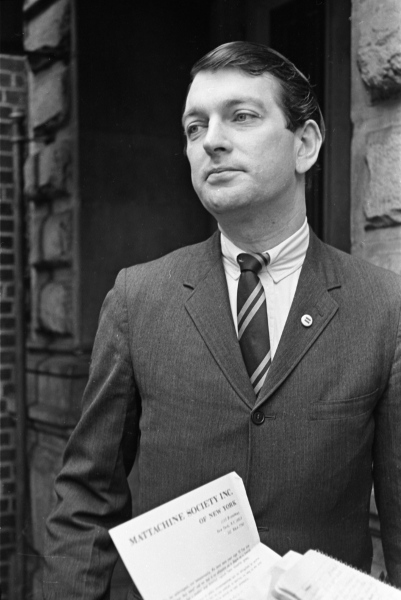

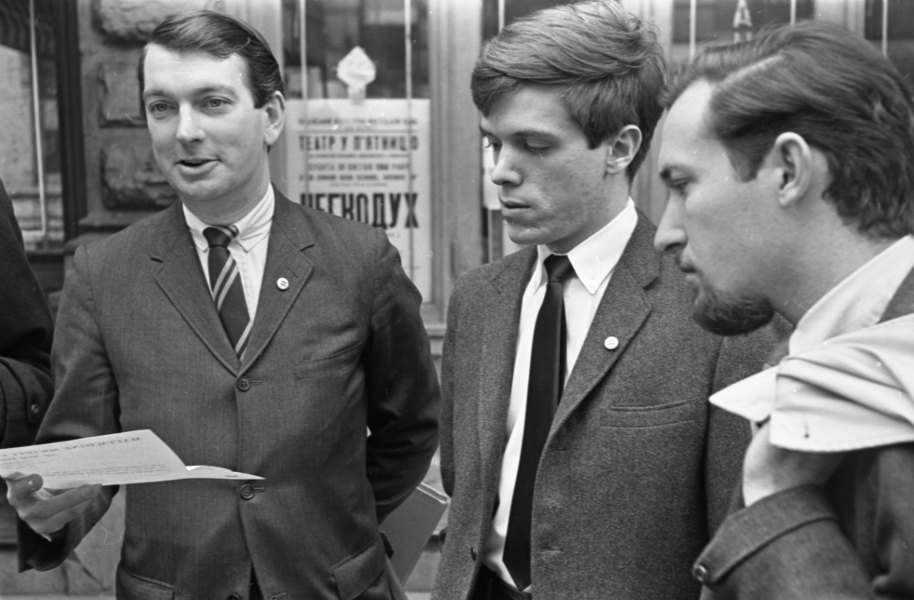

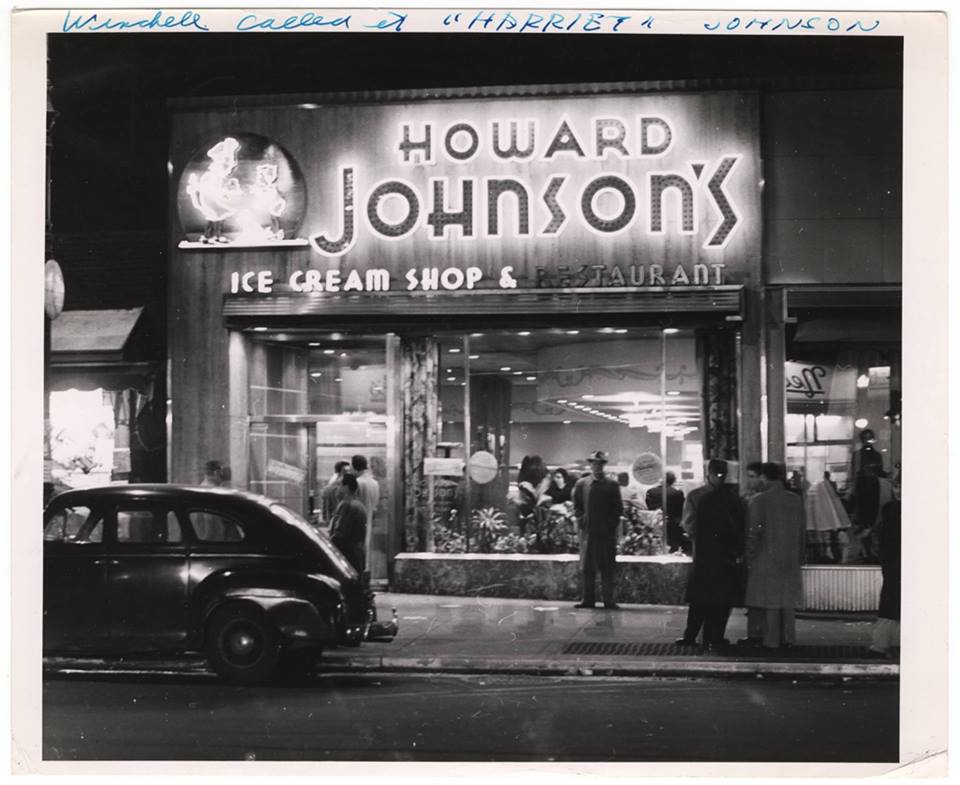

Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell, and John Timmons, accompanied by several reporters, went to a number of bars, announced that they were “homosexuals,” and asked to be served a drink. At their first stop, the Ukrainian-American Village Restaurant, the bar had closed, while at their next two attempts, at a Howard Johnson’s and at the Hawaiian-themed Waikiki, they had been served. They then moved on to Julius’ and were joined by Randy Wicker. However, at Julius’, which had recently been raided, the bartender refused their request. This refusal received publicity in the New York Times and the Village Voice.

…when we walked in, the bartender put glasses in front of us, and we told him that we were gay and we intended to remain orderly, we just wanted service. And he said, hey, you’re gay, I can’t serve you, and he put his hands over the top of the glass, which made wonderful photographs.

The reaction by the State Liquor Authority and the newly empowered New York City Commission on Human Rights resulted in a change in policy and the birth of a more open gay bar culture. Scholars of gay history consider the Sip-In at Julius’ a key event leading to the growth of legitimate gay bars and the development of the bar as the central social space for urban gay men and lesbians.

Landmark Designations for LGBT Significance

In April 2016, through the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project’s extensive research and writing, Julius’ was listed on the National Register of Historic Places by the U.S. Department of the Interior, following the site’s listing, in December 2015, on the New York State Register of Historic Places. In December 2022, based on recommendations by the Project, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated Julius’ a New York City Landmark. The National Register report, LPC designation report, and Project testimony are available in the “Read More” section below.

Entry by Andrew S. Dolkart, project director (March 2017; last revised December 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Unknown

- Year Built: 1826

Sources

Beth Bryant, The Inside Guide to Greenwich Village, Winter-Spring 1964-1965 (New York: Oak Publications, 1964).

David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2004).

Jack Lait and Lee Mortimer, New York Confidential: The Lowdown on the Big Town (Chicago: Ziff-Davis Publishing Co., 1948).

John D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983; second edition, 1998).

Lucy Komisar, “Three Homosexuals in Search of a Drink,” The Village Voice, May 3, 1966, 15.

Petronius (pseud.), New York Unexpurgated (New York: Matrix House, 1966).

Scott Simon, “Remembering a 1966 ‘Sip-In’ for Gay Rights,” NPR, June 28, 2008, n.pr/1kQ69t2. [source of pull quote]

Thomas Johnson, “3 Deviates Invite Exclusion by Bars,” The New York Times, April 22, 1966, 43.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?