Everard Baths

overview

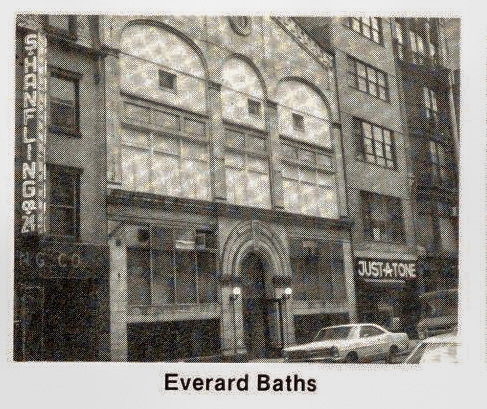

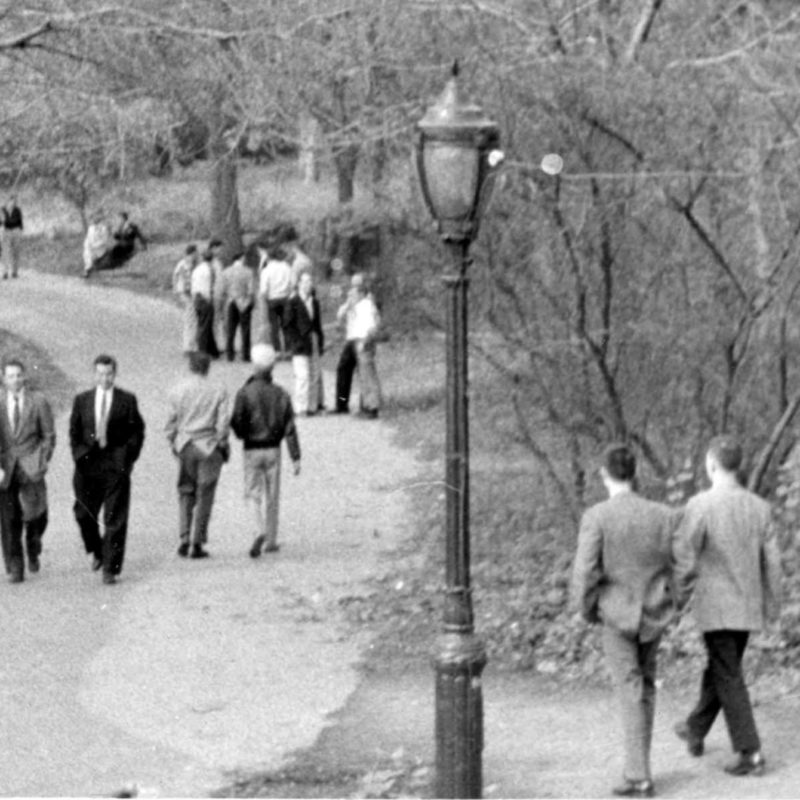

The Everard Baths, one of the most legendary of New York’s bathhouses, was a refuge for gay men probably since its opening in 1888, but definitely by World War I.

As with most of the city’s gay bathhouses, it was closed in 1986 by the City of New York as an anti-AIDS measure.

History

One of the most legendary of New York’s bathhouses, the Everard Baths was a refuge for gay men probably since its opening in 1888, but, as documented, from at least World War I until its closing in 1986.

The building began as the Free Will Baptist Church in 1860. In 1882, it was converted into the New-York Horticultural Society’s Horticultural Hall. In 1886-87, it became the Regent Music Hall, then the Fifth Avenue Music Hall, financed by James Everard.

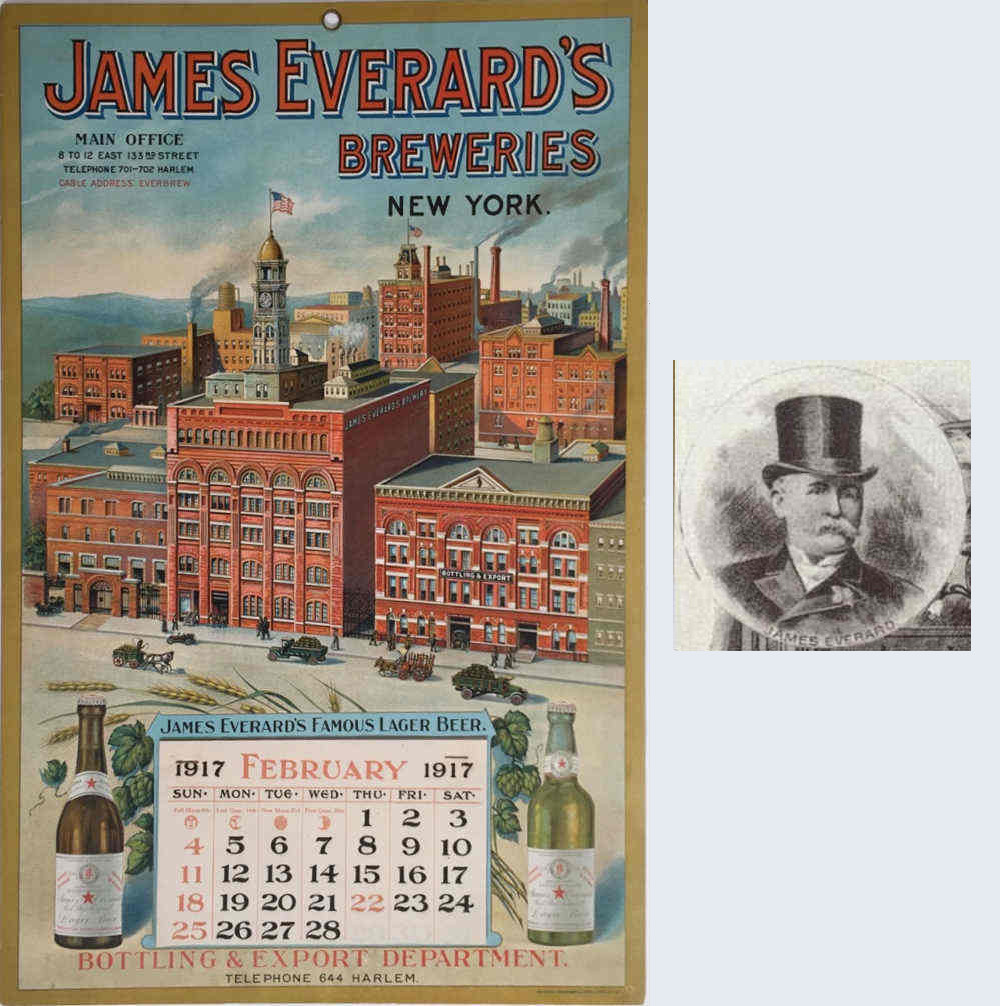

Born in Dublin, Ireland, Everard (1829-1913) came to New York City as a boy, and eventually formed a masonry jobbing business that was successful in receiving a number of major city public works contracts. With his profits, he invested in real estate after 1875, and built up one the country’s largest brewing concerns. (He was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery.)

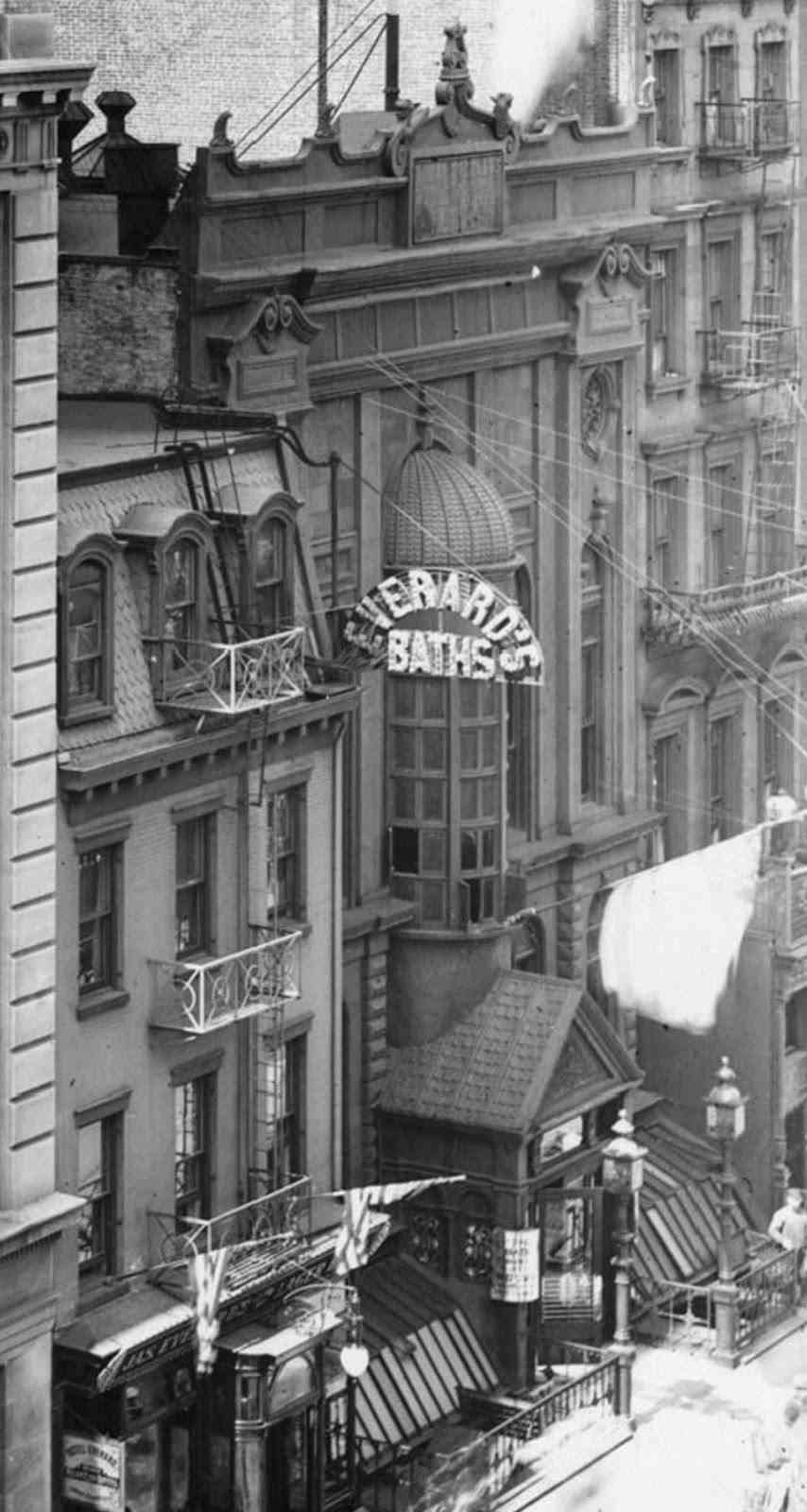

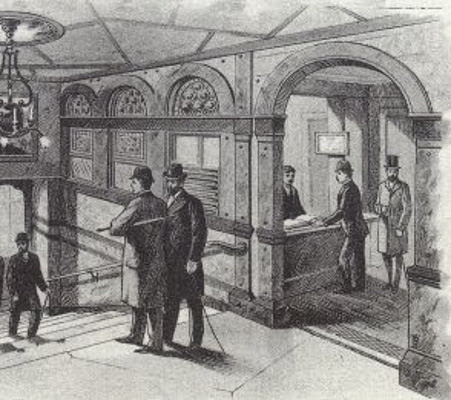

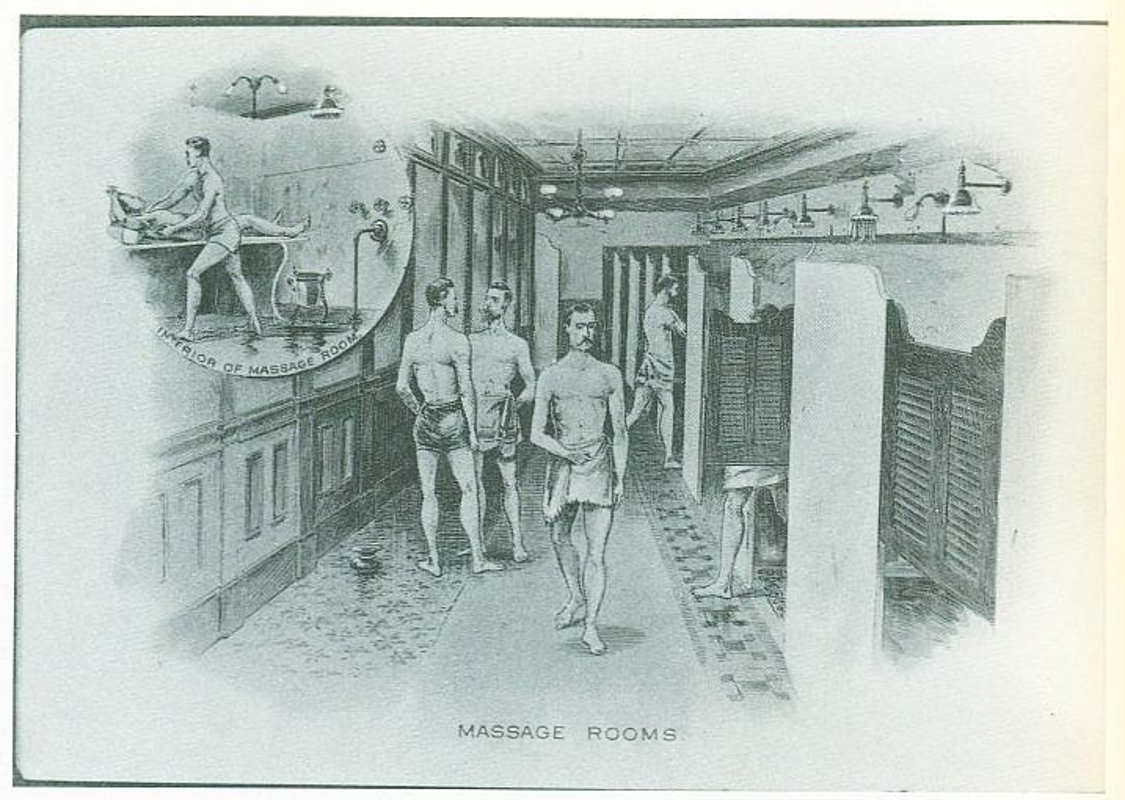

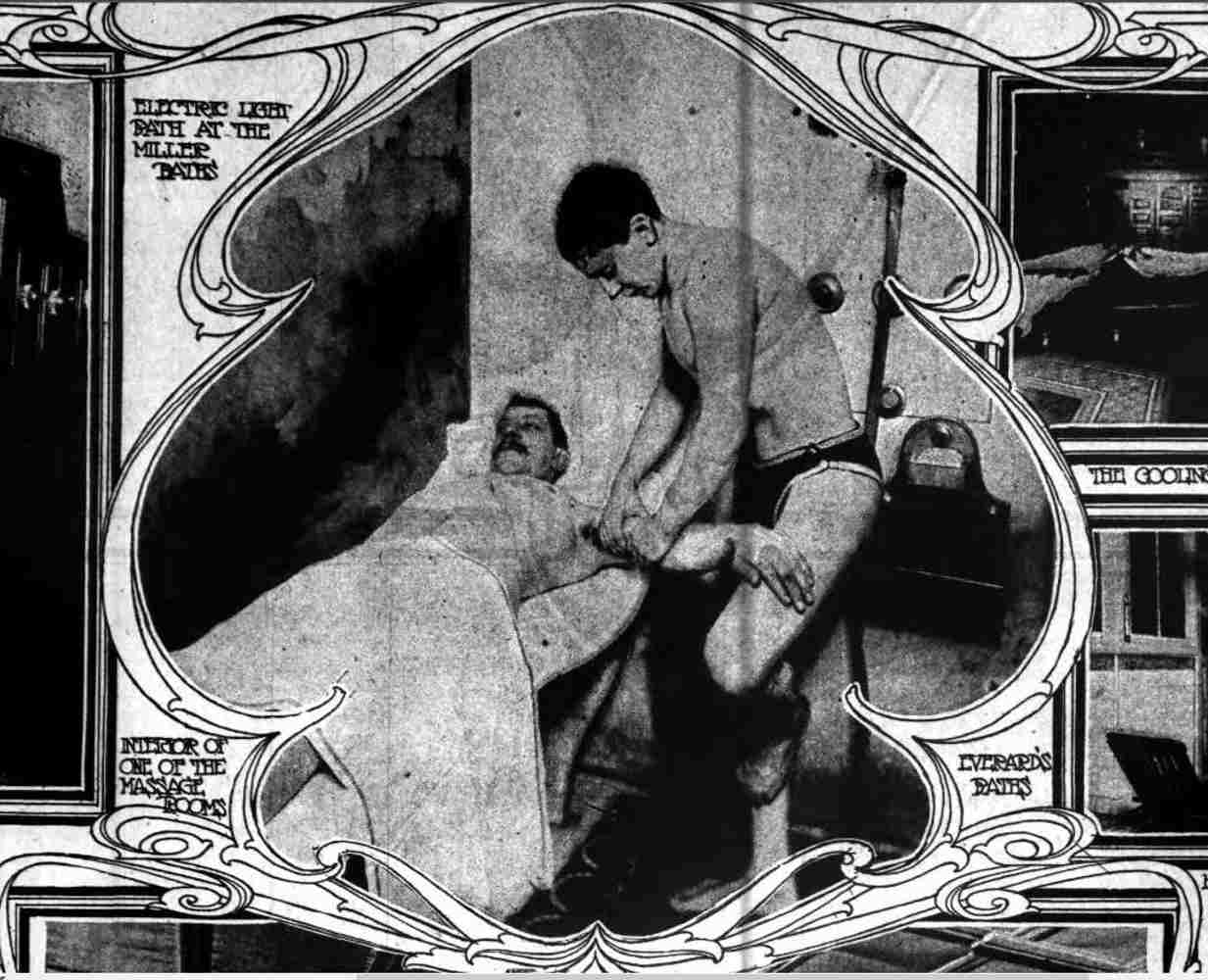

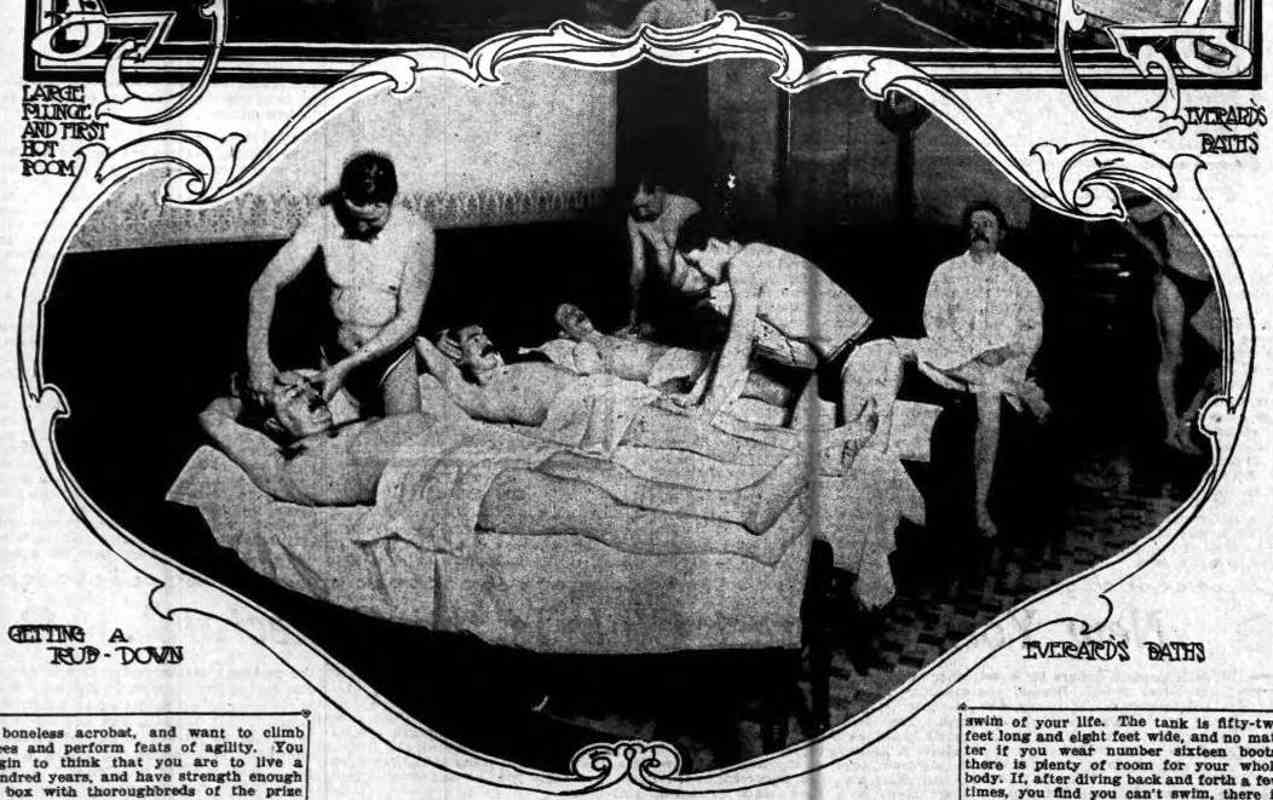

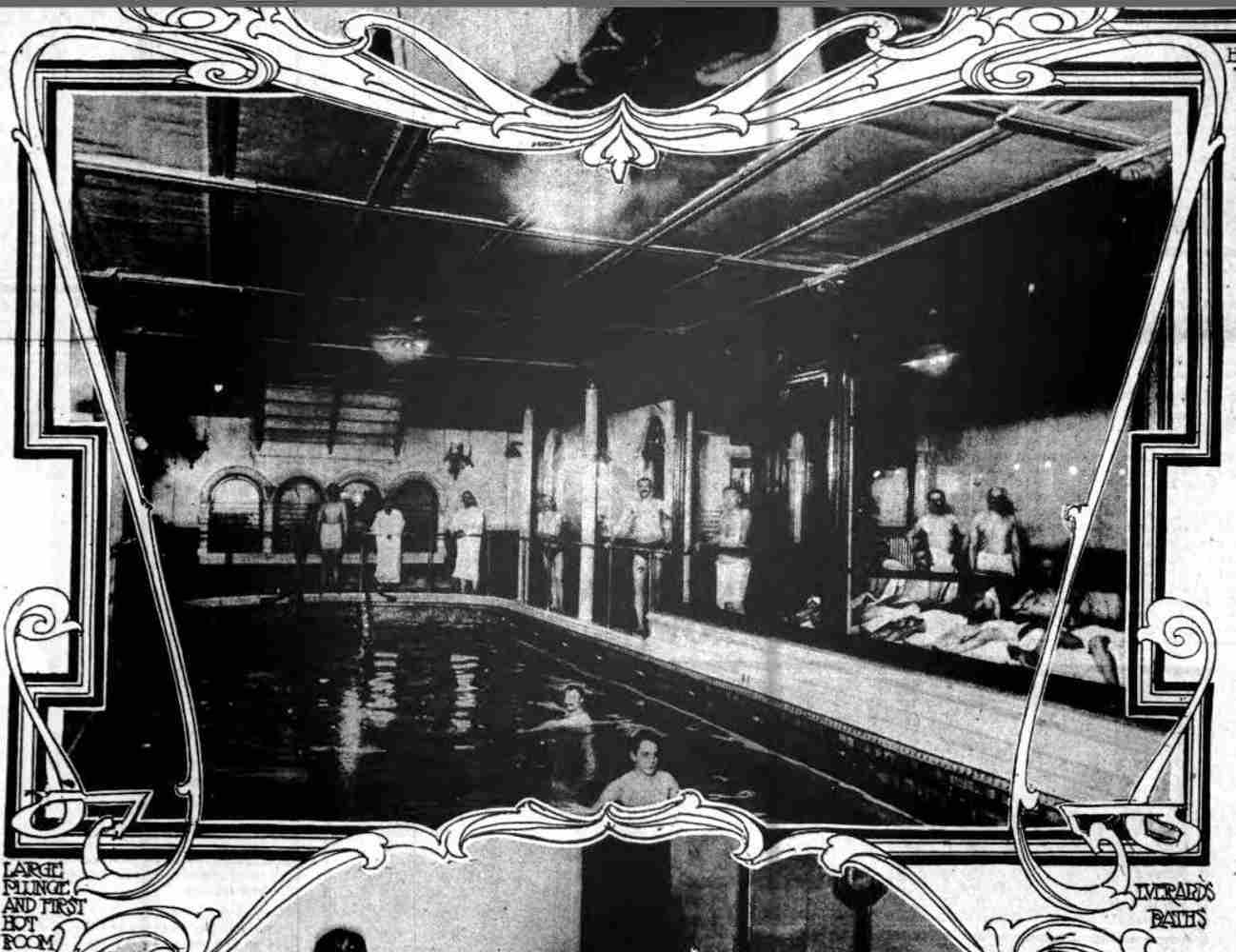

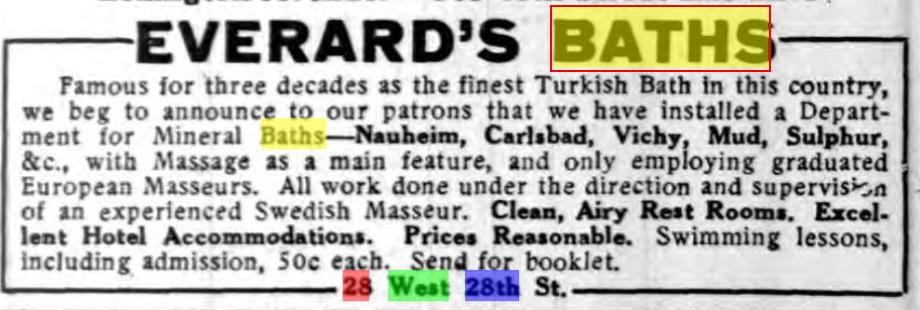

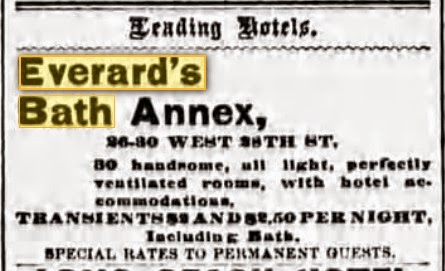

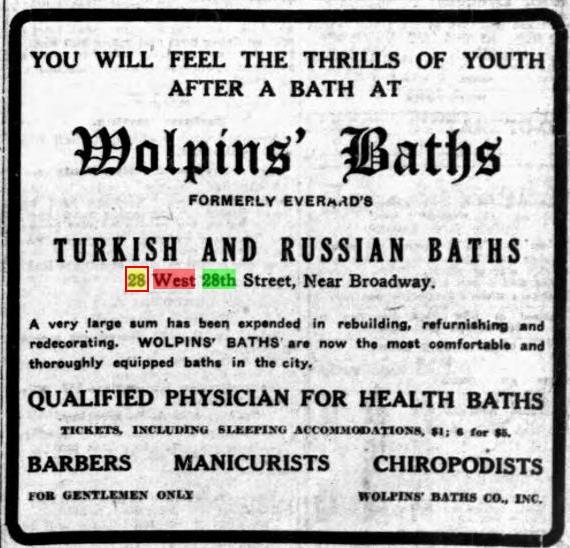

After the Music Hall was closed by the City over the sale of beer there, Everard decided to save his investment by turning the facility into a commercial “Russian and Turkish” bathhouse, opened in May 1888 at a cost of $150,000. Lushly appointed and with a variety of steam baths and 100 sleeping rooms, it had a prime location in the heart of the neighborhood known as the Tenderloin, with its many theaters and other entertainment venues, hotels and bachelor flats, restaurants, brothels, and sex resorts. In its earliest years it had a wealthy and middle-class clientele and an international renown. By 1896 the Everard had an Annex next door at No. 26. After Everard’s death, it was briefly a bathhouse for women only in 1914, and in 1917 it became Wolpins’ Baths, an ad for which stated that “a very large sum has been expended in rebuilding, refurnishing and redecorating.”

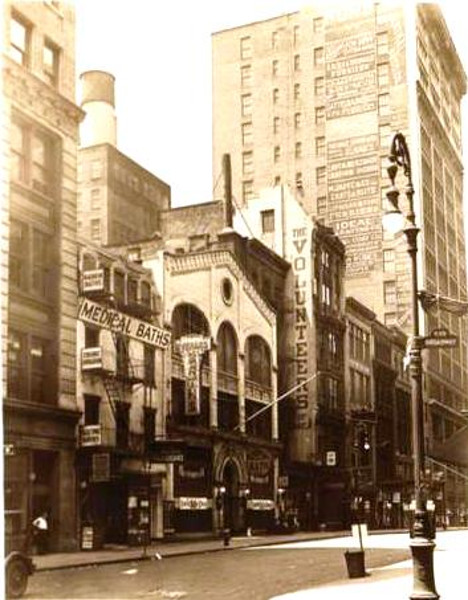

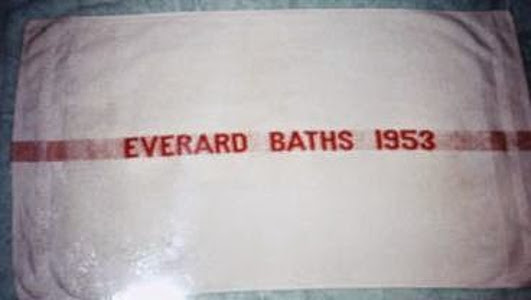

By the 1920s, the Everard was still considered one of the major Turkish bathhouses in Manhattan. George Chauncey found that raids by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice in 1919 and 1920 here produced the arrests of numerous gay men. In 1921, the bathhouse was sold to lawyer Abraham Harawitz, who planned $100,000 worth of alterations and expansion. An ad in 1922 stated “everything new but the location” and boasted that it was the “Most Luxurious Baths in the World.” Another source noted,

Everard’s Turkish Baths…plays a major role in New York’s gay life. On weekend nights, there is almost always a waiting line after 10 PM, sometimes over an hour long for dormitory space and longer yet for rooms.

The quote continues, “Most of the activity takes place in the huge dormitory on the second floor. There are some rooms around this dormitory, but most are on the third floor. Below the street level, for any who may be interested, are found the steam room, showers and even a swimming pool. … There are, of course, many other Turkish Baths in New York. … But [none] of the others, no matter what their occasional activity, can boast of a reputation even approximating that of Everard’s.”

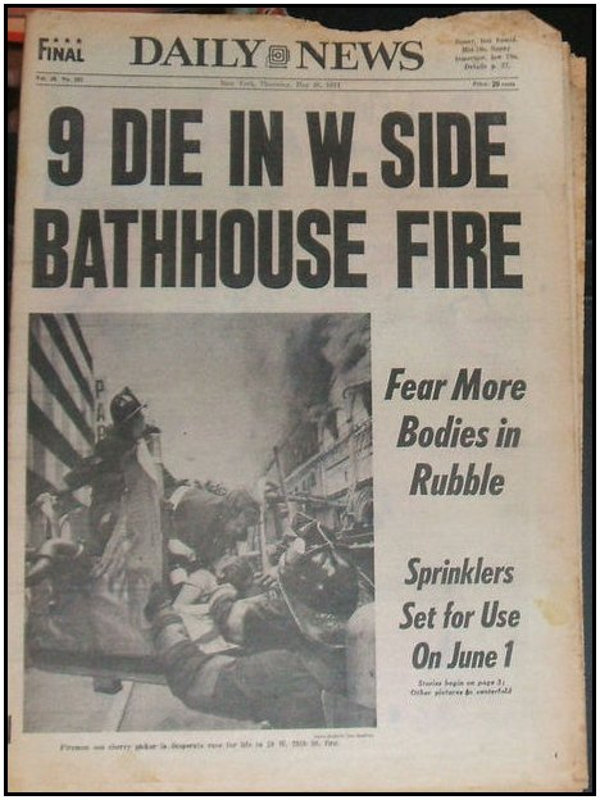

Some of its celebrated patrons are said to have included British actor/playwright Emlyn Williams, Alfred Lunt, Gore Vidal, Rudolf Nureyev, Truman Capote, Larry Kramer, and Ned Rorem. A tragic fire struck on May 25, 1977, when nine men died and the upper two floors were destroyed.

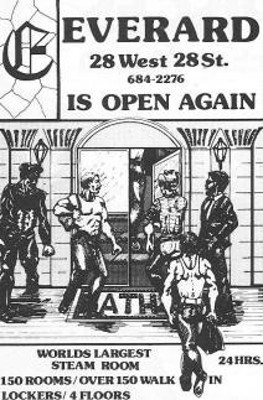

The bathhouse was rebuilt and reopened, with an altered façade, but Mayor Ed Koch closed the Everard for good in April 1986 as an anti-AIDS measure.

Entry by Jay Shockley, project director (March 2017).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Deutsch & Parker (alteration and expansion)

- Year Built: 1860; 1921 (alteration and expansion); 1977 (rebuilt after fire)

Sources

Daniel Hurewitz, Stepping Out: Nine Walks Through New York City’s Gay and Lesbian Past (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1997).

Gaedicker’s Sodom-on-Hudson (Spring 1949).

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994).

Laurie Johnston, “9 Killed in Bath Fire Identified by Friends,” The New York Times, May 27, 1977, 17.

Steven Welch, “Fire in the Everard Baths,” StevenWarRan blog, July 15, 2014, bit.ly/2fQCnXw.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?